Discharge could last through Monday morning

By Joseph T. O’Connor and Amanda Eggert

EBS STAFF

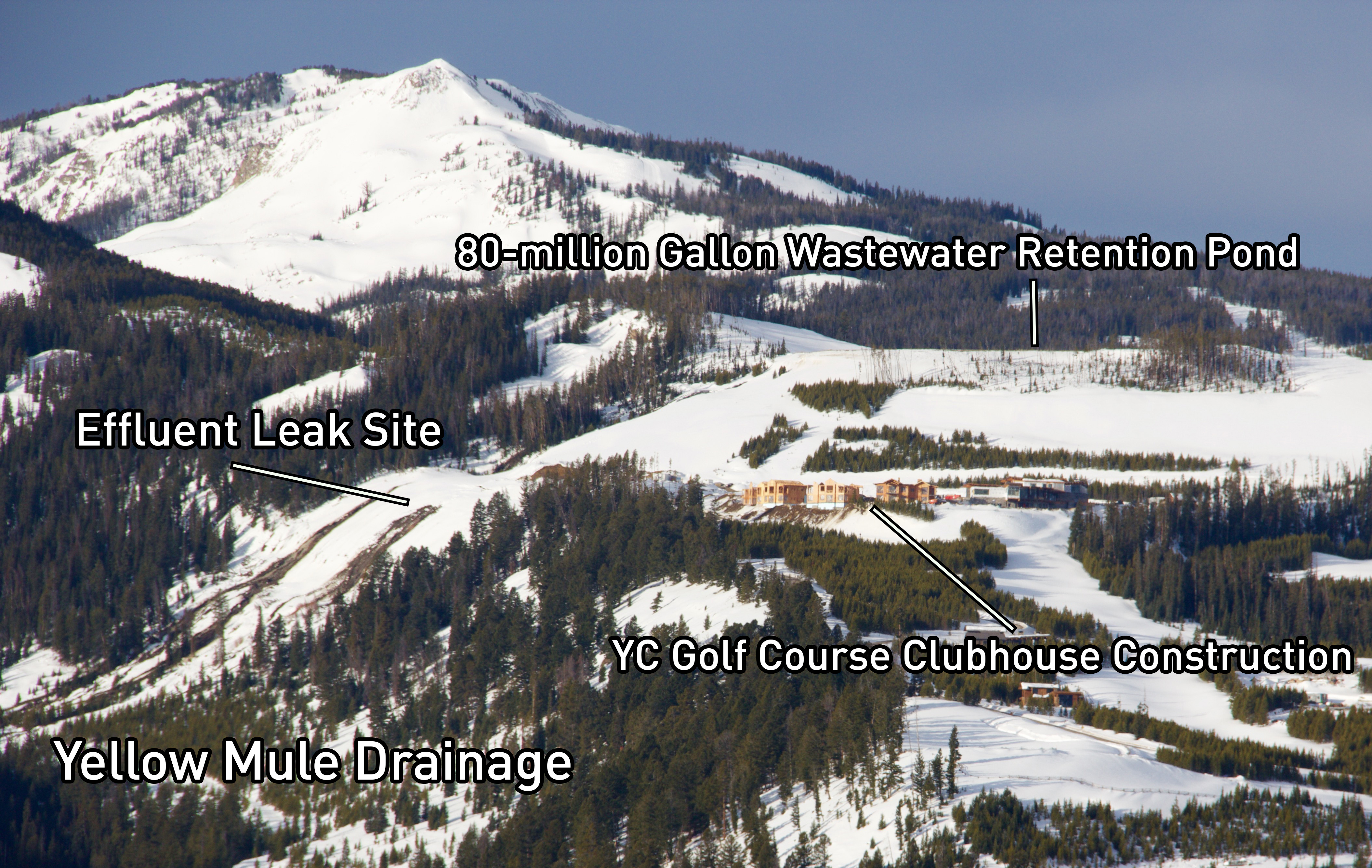

BIG SKY – On Thursday afternoon, a pipe connected to a Yellowstone Club treated wastewater holding pond burst, sending millions of gallons of effluent cascading into a tributary of the Gallatin River.

As of 6 p.m. Saturday, water was still discharging into the South Fork of the West Fork of the Gallatin, and some 25 million gallons of a total 35 million gallons of this wastewater had been lost.

From a helicopter above the spill site, clear water could be seen carving deep trenches in the hillside en route to the waterway. Picking up heavy amounts of sediment along its way, the effluent has turned the South Fork of the West Fork a deep brown color.

Where it meets the main Gallatin River, the turbulent water mixed with the steady stream flow causing a murky hue down the river at least as far as Gallatin Gateway.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said J.C. Knaub, who’s lived in Big Sky since 1973 and owns a home on four acres approximately 200 yards above the confluence of the south fork and the west fork. “It’s really sad this is happening. It’s not intentional but there has to be some liability.”

For its part, the Yellowstone Club has been able to divert some 6 million gallons of effluent into a second holding pond below the breached pond. The wastewater is being diverted via an eight-inch pipe into the lower pond at a rate of approximately 160,000 to 180,000 gallons per hour.

“We expect the flow to stop sometime between tomorrow morning and Monday morning,” said Matt Kidd, Principal at Cross Harbor Capital Partners, which owns the majority shares of the Yellowstone Club. The flow will decrease as the water pressure diminishes, Kidd said.

The current theory is that the broken pipe resulted from an ice formation that formed this winter after workers attempted to fix a previous leak in the pond liner.

In fall 2015, the club drew down the effluent water level in the pond to fix a leak in the liner, according to Mike DuCuennois, vice president of development for the Yellowstone Club. As the Big Sky Water and Sewer District pumped water back into the pond from its sewer plant in the Meadow Village beginning in December, an ice formation formed on the drainpipe at the bottom of the pond.

As the water level continued to rise, the iced-over pipe began pulling out of the pond bottom, ripping the liner and breaking the pipe, DuCuennois said.

Once the effluent flow subsides, DuCuennois said a team of engineers is on standby ready to assess the damage and issue drawings to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, the entity heading up the current investigation.

Water quality specialists with the DEQ began water sampling today and will continue through the weekend, according to an email press release from DEQ Public Policy Director Kristi Ponozzo. Specialists are testing the water for turbidity, pathogens, phosphorus, suspended sediment, ammonia, pharmaceuticals, nitrate plus nitrite, and total nitrogen, the release read.

______

Ponozzo said the DEQ did not expect to have data on turbidity – which is needed to determine the amount of suspended sediment in the waterway – until tomorrow.

Suspended sediment has emerged as one of the leading threats to aquatic life in the watershed. High levels of suspended sediment compromise fish’s ability to breathe. The impact becomes more pronounced the longer the fish are subjected to heavy sediment loads.

Kristin Gardner, the Executive Director of the Gallatin River Task Force, said a high-flow spring runoff event would eventually flush much of the sediment downstream.

Guy Alsentzer, the Founder and Executive Director of Upper Missouri Waterkeeper, received some preliminary results from the water samples he sent to Bridger Analytical Lab in Four Corners.

Alsentzer collected samples from four locations on the Gallatin: near The Corral Bar and Steakhouse, which is upstream of the West Fork and should not be impacted by the spill; the confluence of the West Fork with the main stem of the Gallatin; a site 1.7 miles downstream of the confluence of the West Fork with the main Gallatin; and House Rock, approximately 14 miles north of the confluence.

Alsentzer’s sample showed an E. coli count of 91 MPN/100mL. MPN stands for “the most probable number of bacteria in the sample” and is roughly equivalent to a parts per million reading.

To provide context for comparison, Alsentzer said that the Ennis wastewater treatment facility has an established threshold of 125 E. coli/100mL, but said its presence is never welcome in the waterway and indicative of wastewater entering the Gallatin.

“Basically, any presence of E. coli is considered dangerous,” said Peter Manka, a water resource engineer with Alpine Water in Big Sky. “Anytime you have any presence of E. coli [it’s] a red flag.” He added that deer feces in the river could cause a spike of E. coli in a water sample.

Alsentzer said it’s significant that there was no detectable E. coli in the sample he took upstream of the confluence.

According to Ron Edwards, general manager at the Big Sky Water and Sewer District, these test areas aren’t necessarily indicative of the waterflows coming out of the West Fork of the Gallatin.

“The whole canyon is septic systems and drain fields,” Edwards said. “The [results] could be easily coming from there.”

Edwards noted that initial DEQ tests of the wastewater in the holding pond indicated a residual chlorine level of 0.16 parts per million. “That will kill all bacteria,” he said.

The DEQ should have some test results by early next week, Edwards added, which will offer a definitive picture of whether or not E. coli exists in the water due to the pond breach.

At a public meeting to update the Big Sky community on the spill, county health officials advised concerned citizens to have their wells tested.

“We’re prepared to pay for all well testing in the watershed,” Kidd said Saturday. “We’re willing to do whatever it takes to make it right.”

Watch aerial video of Yellowstone Club spill site: