BSOA and BSCWSD near agreement; river impairment may cause unintended consequences

By Jack Reaney STAFF WRITER

The Big Sky Owners Association’s Little Coyote Pond recovery project is expected to move forward, perhaps faster than the Big Sky County Water and Sewer District’s new Wastewater Resource Recovery Facility, which remains mired in supply chain frustration.

An update to water negotiations between the BSOA and BSCWSD, and further delays to Big Sky’s massive investment in water infrastructure were among topics discussed at the BSCWSD board meeting on Monday, May 15. The other main discussion topic was the Gallatin River’s EPA-confirmed impairment listing, which may hamper the nascent Gallatin Canyon County Water and Sewer District—despite that project’s aim to benefit river health.

Early in the meeting, district board chair Brian Wheeler praised board member Mike DuCuennois.

“You’re the man. You broke the logjam,” Wheeler declared, referencing the BSOA negotiations that morning.

DuCuennois, hours after pinch-hitting for Dick Fast on the district’s BSOA pond subcommittee, gave a summary of their Monday morning meeting with the BSOA board.

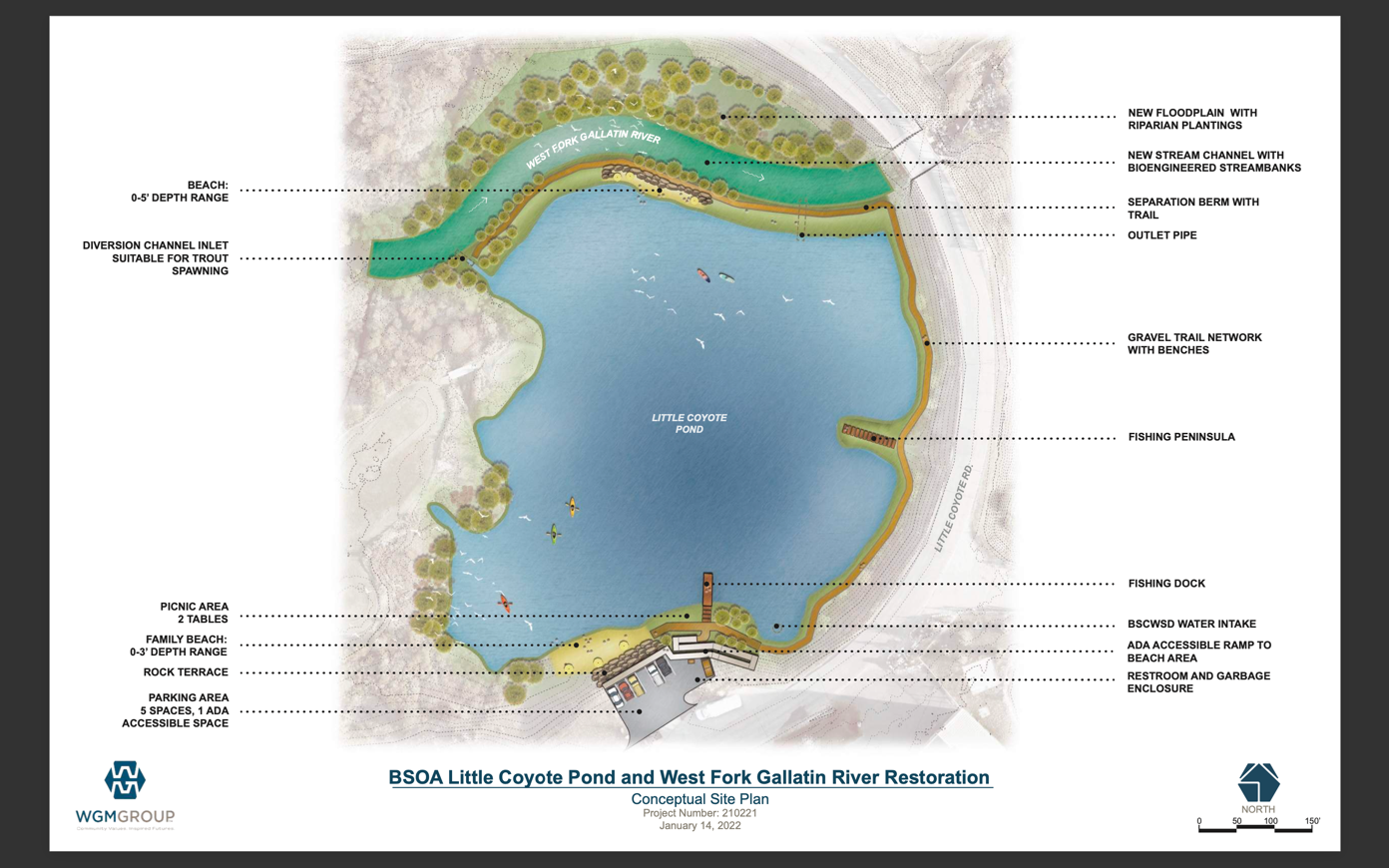

For several years, the BSOA has been pursuing water rights from—and held a memorandum of understanding with—the district to renovate the Little Coyote Pond and restore the West Fork of the Gallatin River.

In recent months, the district has identified a parcel of land owned by NorthWestern Energy on which they hope to build a million-gallon tank for community water storage. But the district would require the BSOA to expand an access easement along Crazy Horse Road and permit a small amount of land in order to build the tank.

Negotiations were terminated and revived just in the past two months, with the BSOA proposing to revert to an eight-year-old memorandum of understanding signed by both parties before BSCWSD had interest in building a water tank—the MOU suggested a cash exchange of “fair market value for the water [rights] conveyed” by the district, according to a May 12 BSOA newsletter.

The newsletter stated that the BSOA executive director tried to pay BSCWSD $15,000 for the Little Coyote Pond fishery water rights to prevent further delays. But on May 9, the district returned the $15,000 check and asked that the May 15 meeting continue as planned.

At the May 15 meeting, an agreement was reached contingent on the water and sewer district purchasing that land from NorthWestern Energy—board member Al Malinowski announced that land had been appraised at $60,000, much less than the board had budgeted for.

DuCuennois summarized: “So there’s been some confusion [on] everybody’s part of what we needed, what they needed, and this [makes] everybody happy, from the meeting we had today.”

One minor disagreement lingered, regarding the future of the 250,000-gallon tank near the proposed upgrade site, built in 1970. The district is hesitant to deconstruct any water storage resources, but Clay Lorinsky, BSOA board vice chair, told the board it must be deconstructed if it’s taken offline.

“I think that’s appropriate and necessary from our side,” Lorinsky said. DuCuennois suggested that if the tank is out of service for four years, it will be deconstructed.

“I think after [the BSOA board] vote happens on Friday unless some nuance comes up, we should be able to modify the existing agreement that we all worked on for so long, to fit these terms and have something on our table fairly quick,” DuCuennois said.

DuCuennois told EBS the recent progress wouldn’t have happened without collaboration between the BSOA and the district.

“All meeting together this morning was a huge benefit to working together and getting it done,” DuCuennois told EBS.

Electric slide

The district continues to extend the timeline for the Big Sky Wastewater Resource Recovery Facility, which was originally expected to finish construction on March 7, 2024.

After initial delays, electrical equipment shortages have furthered that final completion to Oct. 18, 2024. Big Sky is in a long line behind other frustrated projects, waiting for components which will power the network of controls for monitoring and operating the plant.

“There’s potential the building and all the site cleanup will be done, and we’ll be waiting for the electrical equipment so we can run the plant,” district General Manager Ron Edwards said.

As a result of this delay, irrigators including golf courses will have to wait another summer (through 2024) to use the new plant’s highly treated water. In addition, the RiverView apartment complex which recently broke ground had reached a water and sewer agreement conditional on the new plant’s activation. Given the significant delay, RiverView might finish construction before the WRRF, and Edwards said that would be another problem to solve.

Scott Buecker, senior project engineer on the WRRF, spoke to the EBS about the delay. He said it’s not worth pursuing a lawsuit against Systems Integrated, the company handling electricals, because courts aren’t supporting claims for liquidated damages—projects are delayed all over the country, but courts are siding with contractors who claim it’s an “act of God” out of their control.

“Well, it’s unprecedented, let me say that first,” Buecker told EBS. “I’ve never seen anything like this. Industry’s never seen anything like this, so we’re in uncharted territory.”

He acknowledged it’s frustrating for homeowners and district officials.

“But there’s nothing we can do, our hands are tied,” Buecker said. “We can push on Systems Integrated, but they’ve got dozens of other projects around the country pushing as well.”

Some good news around the WRRF did come out of the board meeting: a new storage tank on the east end of the treatment ponds will allow the district to bypass storage ponds during low-flow periods, likely offseason.

That will allow planned pond drainages in which the district can repair any damaged lining without affecting overall water treatment. Edwards called it “new territory” which will benefit the district.

Gallatin River’s impairment could complicate water and sewer improvement

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently approved the Montana Department of Environmental Quality’s decision to list the Gallatin River as impaired after nutrient pollution in the river led to five consecutive years of toxic algal blooms.

As a result, scientists will monitor water quality sampling sites on the river for the next three years in an effort to figure out where the pollutants are coming from. After that, a total maximum daily load of nutrients allowed to enter the river will be set—TMDL is commonly called a “pollution diet.”

The study, which Buecker, Edwards and other officials agreed could take up to six years, might prevent development in the Gallatin Canyon—even “nutrient offsetting” development, like the Gallatin Canyon County Water and Sewer District which is working to bring outdated septic systems onto a central network, carrying wastewater by a pipeline to the new WRRF where it would be treated to a much higher standard than most riverside systems currently do.

The board suggested a joint meeting with the Montana DEQ, and both local water and sewer districts, to understand the implications of the three- to six-year impairment study.

If developers are unable to build homes in the canyon for six years, the entire water and sewer project would lose much of its incentive—the canyon water and sewer district is an initiative led in part by canyon developers.

“I don’t see it as helpful to getting stuff done in the canyon,” Edwards told EBS. “I think it hits the pause button on everything down there… I think it makes new developments in the canyon difficult. It makes working towards solutions in the canyon difficult.”