Journalist Ben Goldfarb sees ‘enormous’ challenge and opportunity for Montana, will stop in Big Sky on June 18

By Jack Reaney ASSOCIATE EDITOR

U.S. Highway 191 isn’t the only road that could benefit from wildlife crossings. Societies around the world are building infrastructure to help wildlife cross highways, and in 2023, environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb published a book about why crossings matter for both people and the ecosystems around them.

Goldfarb, a resident of Salida, Colorado, will visit the Big Sky Community Library on Tuesday, June 18 at 6:30 p.m. to discuss his new book, “Crossings: How Road Ecology is Shaping the Future of our Planet.” The event will be hosted by the Center for Large Landscape Conservation, a Bozeman-based nonprofit working to improve various sites in the Gallatin Canyon for wildlife connectivity and driver safety.

“This is an opportunity to learn about the immense impact that Montana’s highways are having on its wildlife, and to hear from both a journalist and some researchers about what potential solutions are,” Goldfarb told EBS.

After a reading by Goldfarb, leaders from CLLC will guide a Q&A discussion, moderated by Joe O’Connor, Big Sky resident and managing editor of Mountain Journal.

Liz Fairbank, CLLC road ecologist, said Goldfarb has been doing his homework on this topic for a long time.

“It’s really awesome to see a popular piece done about road ecology, it’s the first one I’ve seen,” Fairbank told EBS in a phone call. She’s almost finished reading “Crossings,” and believes it’s the only road ecology book “meant for popular consumption” with an engaging story, and without too much technical detail.

CLLC will also host Goldfarb for his Montana book tour in Livingston, Corvallis, Bozeman, Missoula and Whitefish.

Fairbank hopes the events will illustrate broad challenges and solutions in road ecology, as Goldfarb shares stories of humans across wide-ranging landscapes and their impacts on wildlife connectivity.

“The main thing that I’m hoping that people get out of it is just realizing that this work is happening all over the world,” Fairbank said.

‘Can Montana remain a leader in this field?’

In a Zoom interview with Explore Big Sky, Goldfarb said he sees his book as journalism, not environmental advocacy.

“I embarked on this project willing to go wherever the scientific evidence took me,” he said. “When you read the scientific literature about wildlife crossings, it’s overwhelming in how effective they are.”

If scientific evidence showed crossings aren’t effective, Goldfarb said the book would have concluded as such.

“Research conducted by many people a lot smarter than me has shown that these structures are very valuable,” he said. “The book is really just following this large body of evidence about how well these solutions work.”

Goldfarb’s inspiration came in October 2013.

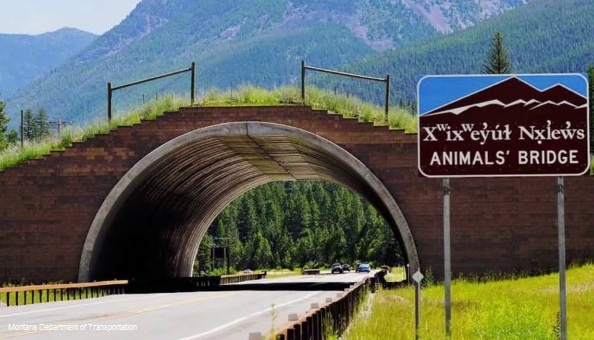

While traveling around the Rockies to write about habitat fragmentation and wildlife connectivity, he was inspired by the “famous” series of wildlife crossings on U.S. Highway 93, north of Missoula on the Flathead reservation.

For two reasons, he said, “It was just incredibly eye opening.”

First, human infrastructure has historically challenged wildlife—this was designed for their benefit.

“I found that inspiring, and kind of beautiful,” he said.

Second, Goldfarb was fascinated by the intellectual challenge of designing crossings so a specific variety of animals would actually trust and use them.

“How do you create a built piece of infrastructure that’s enticing to an elk, or a grizzly bear, or a bobcat or a meadow vole—the whole ecosystem of critters whose lives are fragmented by highways, and who all have to cross the road safely,” he said.

Since the publishing of his book in September 2023, Goldfarb has visited almost every western state—all of which are exploring wildlife crossings—to share what he learned.

Although Montana took the lead two decades ago, momentum has flatlined.

“[Montana is] this historic leader in the field, thanks largely to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, who pushed for those [Highway 93] crossings in the early 2000s. But now there are other states like California, Utah and Colorado that are doing more of this work,” Goldfarb said. “Can Montana remain a leader in this field? I think that’s one of its challenges going forward.”

Goldfarb finds Montana interesting because it’s full of wildlife, and vehicle-wildlife conflict as a result. Montana has an “enormous” wildlife collision problem, he said—usually the second-highest rate of wildlife collisions, behind West Virginia, but involving larger animals like elk.

Montana is also home to some of the country’s most relatively intact ecosystems, threatened primarily by the highways bisecting them. Especially for grizzly bears, a species that often defines Montana’s enduring wilderness, roads are a barrier.

“Grizzly bears really don’t cross highways readily,” Goldfarb said. “… For a grizzly bear, a road might only be 100 feet wide from shoulder to shoulder, but it can prevent them from accessing hundreds of thousands of acres of really good habitat.”

In one well-known example, a collared grizzly in Montana named “Lingenpolter” attempted to cross Interstate 90 at least 46 times between Nov. 15, 2020 and May 3, 2021, before finally succeeding.

“I can’t think of a place that’s more ripe for wildlife crossings than Montana,” Goldfarb said.

The world’s most exciting wildlife crossings

On Washington’s Snoqualmie Pass, southeast of Seattle, Goldfarb knows an “awesome” set of more than 20 wildlife crossings on Interstate 90. Off the top of his head, that project is his choice for the world’s most exciting.

The crossings support an entire ecosystem, with small structures designed for critters like western toads, alligator lizards, weasels and rodents. It’s important to accommodate large animals, “but it’s also important to account for the smaller animals too, and the rarer animals. The animals that aren’t necessarily totaling peoples’ cars,” he said.

The crossings took roughly 10 years of design and advocacy from ecologists, and construction finally began in 2009 in tandem with other I-90 reconstruction. Piggybacking on other construction tends to help wildlife crossing projects advance, Goldfarb explained.

Cost is the main challenge.

Wildlife overpasses, just one type of crossing, typically cost between eight and 10 million dollars, Goldfarb said. That can create some sticker shock, even though the structures are known to save money for citizens in the long run.

“Research conducted by many people a lot smarter than me has shown that these structures are very valuable. The book is really just following this large body of evidence about how well these solutions work.”

Ben Goldfarb, environmental journalist

Despite cost, Goldfarb’s research tells him that wildlife crossings are simply good public policy: they protect human safety and property, while preserving ecosystems as an added benefit.

“If you can build these structures with fences alongside them that prevent a lot of these collisions, then you can save human lives and save the public quite a bit of money in the long run,” he explained.

Goldfarb believes that states’ departments of transportation must break their inertia. Traditionally focused on moving people from point A to B, they are beginning to explore the ecological impacts of highways and potential solutions.

“In some ways, that’s the biggest obstacle. Just getting DOTs to understand that this really is part of what they do, and it’s part of their responsibility,” Goldfarb said. First influenced by a Forest Service ecologist, that’s what happened in Washington.

Right now, Montana is regaining its momentum with guidance from CLLC.

“They have this major push happening right now for wildlife crossings for the Gallatin Valley and all over Montana, and all over the American West,” Goldfarb said.

A survey of Colorado residents showed 85% would favor more wildlife crossings, he said. Although public opinion isn’t usually an obstacle, Montana’s potential to continue fixing problems created by its own infrastructure will be stronger with public support.

In Goldfarb’s view, road ecology is as important a science as ever. Next week, he’ll stop in Montana to explain why.