New Custer Gallatin plan product of extensive collaboration

By Gabrielle Gasser ASSOCIATE EDITOR

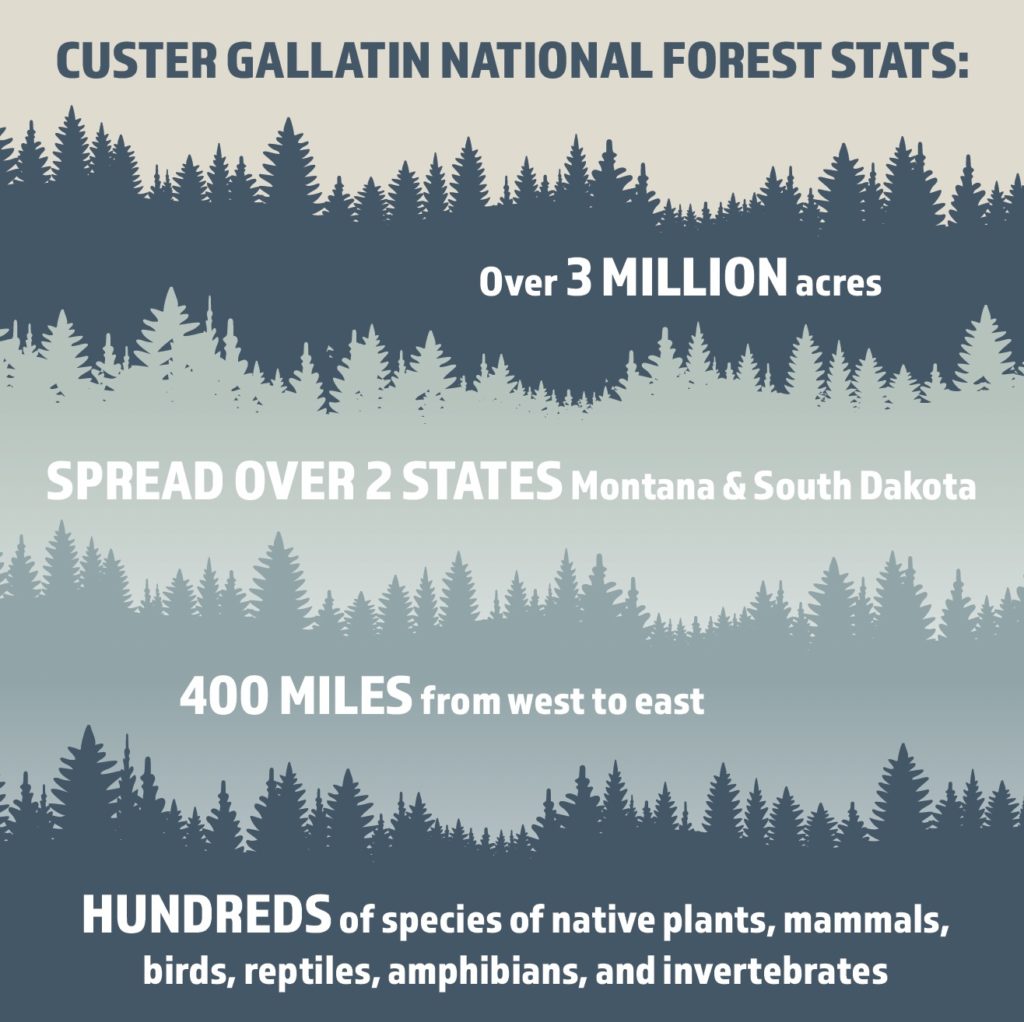

BIG SKY – After six years of extensive public engagement, the U.S. Forest Service on Jan. 28 released an overarching revised land management plan for the Custer Gallatin National Forest. Left without updates since the 1980s, the plan will serve as the guiding document for the highly diverse, more than 3-million-acre forest for up to 15 years.

Forest Supervisor Mary Erickson signed the record of decision for the plan, a long-awaited moment which resulted from far-reaching collaboration across diverse stakeholders including 18 tribes, local governments, state and federal agencies and numerous individuals.

“One of the great advantages of working in a place like this, in the Custer Gallatin, is that people care deeply about this place,” Erickson said at a Jan. 28 press conference. “There was just tremendous interest from the time we began this process all the way through the six years.”

Forest plans are intended to be updated every 10 to 15 years but according to Mariah Leuschen-Lonergan, public affairs officer for CGNF, the Forest Service’s capability hinges on funding from Congress.

A new USDA Forest Service planning rule implemented in 2012 created a focus on sustainability requiring plans to include sustainable forest restoration, climate resilience, watershed protection, wildlife conservation, ecosystem services, recreation, and uses such as grazing, timber harvest and mining.

That new rule triggered a nationwide review of needed forest plan revisions and identified the Custer Gallatin as one forest requiring an update since the last plan was written in the late ‘80s. The Custer and Gallatin forests were separate until 2014 when they were administratively combined to create one contiguous forest that spans 400 miles east to west.

As part of the planning process, the forest was divided into six geographic areas: the Sioux Ranger District; the Ashland Ranger District; the Pryor Mountains; the Absaroka Beartooth Mountains; the Bridger, Bangtail, and Crazy Mountains; and the Madison, Henrys Lake, and Gallatin Mountains.

Key decisions in the revised plan address native species, designated areas, wildfire and protection of communities, sustaining the forest, and human values and uses.

“There’s a lot of pressures on these landscapes, there’s a lot of values, and the plan lays out our framework for sustaining the forest over time,” Erickson said.

Designated areas created through the planning process include eight Recommended Wilderness Areas, 13 Backcountry Areas, two Key Linkage Areas, 10 Recreation Emphasis Areas, 30 eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers, and one platinum and palladium mine.

Rivers identified as eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers are protected for their outstanding remarkable value, keeping the rivers free flowing, and maintaining the assigned tentative classifications for each river segment. The 30 rivers found by the plan to be eligible for this designation equate to approximately 433 miles.

In August 2018 Congress designated 20 miles of East Rosebud Creek as part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Thirteen miles of this creek are classified as wild and 7 miles as recreational both as part of outstanding remarkable values.

“In the first stages of this, we had a bunch of people involved in these meetings, who really honestly never had any intent of collaborating on anything,” said Big Sky resident Steve Johnson. “There were significant factions on both extreme ends of, you know, it’s my way or no way.”

Johnson has been involved in the process since early conversations about a decade ago. At a certain point, he said, it became clear that a collaborative agreement wasn’t going to happen.

In the interest of providing cohesive feedback to CGNF, Johnson and other individuals from the surrounding area formed the Gallatin Forest Partnership in 2016 and submitted the final Gallatin Forest Partnership Agreement to the forest service in 2018. Johnson said that agreement became the basis for the plan the forest service ultimately produced.

The agreement details a future for the Gallatin and Madison Ranges that protects wildlife, clean water, wilderness and recreation opportunities through recommended protections and wildlife management areas. Specifically, the document incorporates new land protections that will help guard clean water and ensure safe passage for wildlife while maintaining existing recreational opportunities and seeking to limit new development.

“[The partners] came to the table with a spirit of ‘let’s work something out’ and we did,” Johnson said in a Feb. 7 interview. “I’m tremendously proud to have been a part of that. And given what’s going on in the country these days, anything that actually comes to an agreement amongst disparate parties is sort of a miracle.”

Leuschen-Lonergan explained that the recommended wilderness and type of land allocations drew some of the most diverse perspectives and sparked the most disagreements. The balance of sustainability and preserving public access struck by the plan was informed by focusing on the common ground in the extensive public comment received by the forest.

“It was a pretty lengthy process, and we’re very thankful and fortunate to have people … across the Custer Gallatin, all seven districts, that really care about and are passionate about these public lands and want to be involved in the process,” she told EBS. “Because of that, we were able to build a more … inclusive and robust plan that as we move forward for the next 10 to 15 years, incorporates a lot of people’s thoughts and perspectives and is a better plan because of the involvement that we had.”