Local death in Beehive adds to national total

By Bella Butler EBS STAFF

Matt Clanton jokes with his friends that the reason they volunteer with the search and rescue unit in Big Sky is that one day they’ll need it. With each rescue they collect karmic points to be stashed away in some celestial cache. This winter season, Clanton cashed in his points.

A Big Sky local for the last four years, Clanton, 30, took a trip with friends in January to Cooke City, near the northeast entrance to Yellowstone National Park, called a “mecca of backcountry skiing” in a 2020 Freeskier magazine article. Among the crew’s various objectives was The Fin, a steep, fin-shaped aspect on Mount Republic in the Beartooth Mountains.

After crossing off other big lines earlier in the trip on what they’d concluded was stable snow, Clanton’s group of three paired with another trio to ascend The Fin. When the experienced group reached the field they intended to descend, they dug two snow pits to analyze the stability of the snowpack. Their tests indicated stable snow and they greenlighted the slope before making for the summit about 400 yards above them.

The skiers crossed over a slight aspect change, a seemingly benign decision at the time that in actuality put them atop a snowpack half as deep as where they’d dug their pits. They continued cutting upward across the snowfield until Clanton heard the “whumph”—a dreaded sign in the backcountry that something has gone terribly wrong.

“I swear I saw [the snow] drop from my knees to my shins,” Clanton said, recalling the moment in a recent interview.

Then a skier ahead of him shouted, “Above!”

“We look up and … it just looks like a dragon coming out of the clouds essentially, just this crazy amount of snow coming down,” Clanton said.

He watched as the two skiers ahead of him were swept up by the avalanche, like rocks on the beach when the tide comes in, he remembers. Soon after, Clanton was knocked on his back. He saw a blur of blackness as he went under the snow and then blue again when he’d resurface. He hit something hard and sailed over a band of cliffs.

When the slide hit Clanton, he remembers thinking “I’m not wearing a helmet. I’m going to die.”

Though he sustained severe injuries and was evacuated in a helicopter to emergency care, Clanton and his party all lived. Months after his accident, Clanton has returned to backcountry touring with his injuries mostly healed and gratitude for his life and more respect for the mountains.

But this story could have ended drastically different. In fact, for 36 other backcountry users in the United States this past season, it did.

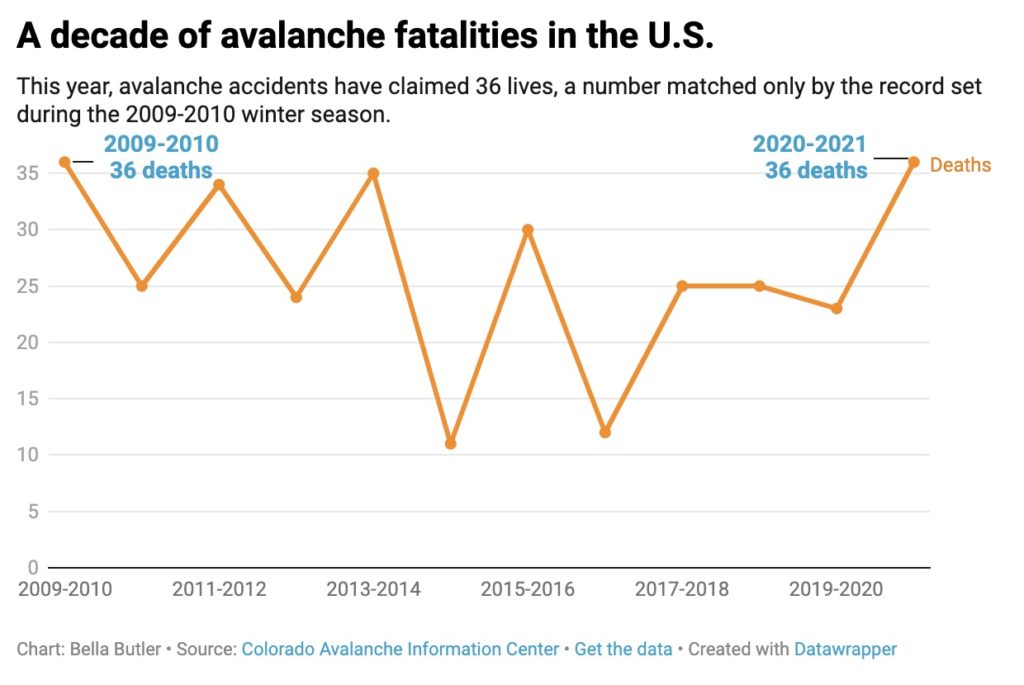

In a pandemic year that has already forced confrontation with mortality, a notably high number of people died in the backcountry this season, matching the modern record of 36 set during the 2009-2010 winter season. And winter in the mountains isn’t over.

According to Ethan Greene, director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, the modern avalanche accident period is considered post-1950, a general timestamp for when people getting caught in avy accidents were also recreating in the snow.

In an April 16 interview, Greene described this season as “difficult and challenging.” Colorado has recorded 12 avalanche deaths this year, leading the U.S. with one-third of the overall total.

Why so many this season? Greene says the devil is in the details.

“In order to get a fatal avalanche accident, you need people that are exposed to an avalanche hazard and an avalanche hazard that is capable of killing people,” Greene said. “This year was, in some ways, a terrible confluence of those factors.”

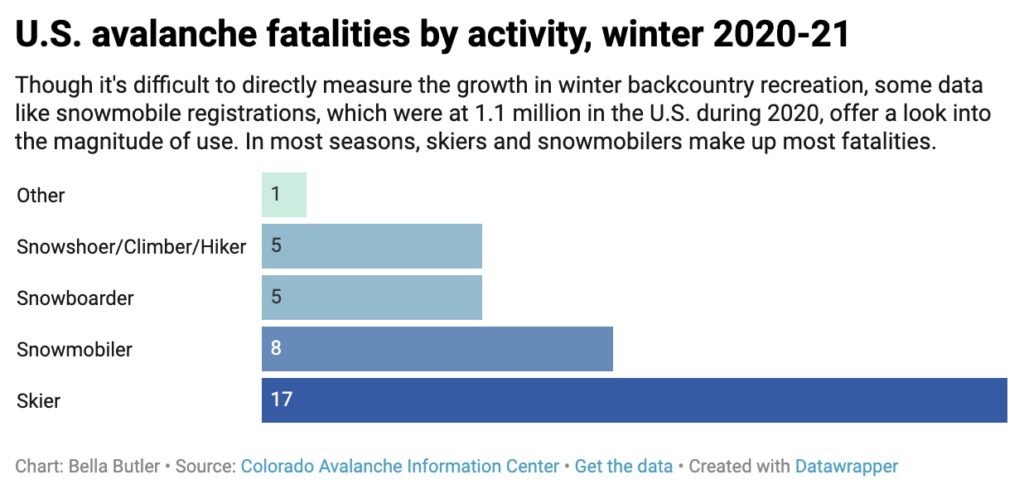

Greene says that backcountry recreation has been on a steady incline for years, a trend supported mostly through anecdotal evidence. This year, interest expanded at a more rapid rate, Greene said. Many in the outdoor industry, including Greene, have speculated that the pandemic has played a major role in pushing more people to recreate on public lands, both in summer and winter.

“If you looked at the last 20 years there would be an upward trend, but the slope of that trend certainly felt steeper in the last 12 months,” Greene said.

In Greene’s catastrophic recipe for an avalanche fatality, that explains the people. The other component is snow. In Colorado, Greene says, the avalanche information center ranked this year as an event that might occur once in 10 years based on snowpack instability and weakness.

Colorado’s snowpack is continental, one of the weakest in the country. Unlike a maritime snowpack in the Pacific Northwest and California, which experiences avalanche hazard as a result of storms coming in and out, the continental snowpack suffers from persistent structural weaknesses that make the post-storm healing process much slower than near the coast.

The snowpack in Montana is considered intermountain, meaning it’s somewhere between continental and maritime and less consistent year over year. This past season, Montana contributed two deaths to the national total: one snowmobiler on Feb. 6 northeast of Flathead Lake, and one splitboarder in Beehive Basin near Big Sky on Feb. 14.

A month after his own accident, Clanton remembers getting the search and rescue call with his girlfriend, who is also on search and rescue, to respond to the Beehive incident. Still injured, Clanton wasn’t able to respond on his own splitboard, but drove his girlfriend and other responders to the trailhead where he offered background support while several groups skinned toward the slide site.

Responders were able to transport the victim, Craig Kitto, a Bozeman school principal, off site and eventually to Bozeman Health Deaconess Hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries later that night.

During the rescue, Clanton felt goosebumps down his spine. “That was me a month ago,” he recalls thinking.

Kitto and the 35 other lives claimed by avalanches this year have, like those before them, left a wound in the community of backcountry skiers that spans mountain ranges and states.

“They’re just devastating to the communities,” said Alex Marienthal, a forecaster with the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center. “It’s never expected, and it always has a big ripple effect through quite a few people.”

Marienthal says there’s always room for improvement, especially when it comes to education, but many involved in avalanche accidents this season have been experienced backcountry users, like Clanton.

“The most basic thing that can be done is to share experiences,” Marienthal said. “People have close calls and no one hears about it because no one got badly injured or needed a rescue or got killed.” He said that sharing those close calls with peers could go a long way toward awareness.

Locally, the GNFAC has wrapped up its forecasting season. Nearly 7,000 people received the daily forecast during the season.