Eminent domain law pits Montana landowners against

growth and big business.

Story and photos by Emily Stifler, Explore Big Sky Managing Editor

Marie Garrison is a fourth generation Montanan, a

rancher and farmer, and a very concerned mother.

Garrison lives on a 4,500-acre ranch in Divide, south

of Butte, with her husband and two young children.

It’s land her husband inherited from his family, and the

Garrisons today run 350 head of mother cows there.

NorthWestern Energy has proposed to build a high

voltage transmission line that would run through the

Garrisons’ property on its way from Townsend, Mont.

to a substation near Jerome, Idaho. The permit could

be issued to the utility company in late 2012, at which

time it could further negotiate with landowners and

start condemnation proceedings, if necessary.

NorthWestern’s ability to exercise the power of

eminent domain for the Mountain States Transmission

Intertie (MSTI) was granted by House Bill

198, which was passed by the 2011 Legislature and

was allowed to become law without

Gov. Schweitzer’s signature or veto.

The new law allows private utility

companies to use eminent domain to

condemn private property for public

use and private corporate projects.

Landowners like Garrison argue this

is an unprecedented infringement on

property rights, while proponents of the bill say it’s

necessary for economic growth.

Garrison says the family would lose 300 acres to the

MSTI line between the access road and the proposed

24 ‘Guy V’ structures, which take up half an acre

each.

“[But mostly], the health effects scare the heck out

of me,” she said. “We have two small children and I

don’t care if it’s one in a million, if it increases their

likelihood of childhood leukemia or brain cancer, no

amount of money is worth it.”

[dcs_img_left desc=”The proposed MSTI line would run through the Whitehall area”

framed=”black” w=”250″ h=”135″]

https://www.explorebigsky.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/jefferson-valley.jpg[/dcs_img_left]

The Garrisons’ ranch already has three, 230-kilovolt

wooden ‘H’ poles running across it. Her

husband’s grandfather sold those easements to the

power company for $1 in the ‘50s, and the lines

bring power to nearby Bannack and Dillon.

“That’s transporting power to the neighbors.

That, to us, is a public use,” Garrison said.

She’s afraid HB 198 puts property owners in jeopardy

of losing land to anyone who wants to come

in and build something for profit.

In 2009, because of that concern, Garrison and

her neighbors started movemsti.com and Concerned

Citizens Montana, a website and organization

to fight for landowners’ rights.

These evolved into votefor125.com, a statewide

grassroots movement by citizens, lawmakers and

organizations concerned about the future of Montana

private property rights. They’re petitioning to get a

ballot initiative, Initiative Referendum-125 (IR-125),

on the November 2012 ballot that would repeal HB

198. The group would have to collect 24,337 signatures,

representing 34 districts, before Sept. 30, 2011.

Eminent domain in Montana

The power of public service companies to claim land

for themselves is nothing new for Montana, which

has had an eminent domain law since 1877.

Today, the law reads, “eminent domain is the right

of the state to take private property for public use.”

It sets out 45 specific public uses for which this

power may be exercised; among them roads, utilities,

public buildings, water supply systems, agriculture,

logging and mining. The condemner must

show “by a preponderance of the evidence” that the

public interest requires the taking.

HB 198 is being interpreted in different ways, with

the two sides arguing whether or not the process for

gaining the power of eminent domain has changed.

Its proponents—backers of utility expansion

projects and big merchant transmission lines like

MSTI—say that when the state put the law on the

books, they identified a number of private parties

(like telegraph companies, railroads, agriculture and

mining companies) as having the right to condemn

private property for public use. So, in their eyes 198

clarifies the original law that was in place for 100

years.

Opponents of HB 198 say this is the first time in

Montana history that a merchant (for profit) line has

this power. They’re concerned it’s become too easy

to gain the power of eminent domain.

House Bill 198

In a December 2010 Glacier County lawsuit, District

Judge Laurie McKinnon ruled that there wasn’t

an existing statute conferring the power of eminent

domain to a private entity.

Following McKinnon’s ruling, the group proposing

the Montana-Alberta Tie Line (MATL, another

high voltage power line), along with NorthWestern

Energy and Montana Dakota Utilities, lobbied the

state legislature, requesting that existing eminent

domain statutes apply to all entities providing

those 45 specified uses. Since some of these are

only built by private entities (roads, utilities,

mining and pipelines, for example), that meant

private interests would be granted the state’s

power of eminent domain.

“[HB 198] doesn’t change the regulatory process,

landowner compensation, due process, or the requirement

to negotiate with individual landowners

on such things as centerline and pole location

within the state-approved corridor,” said Darryl

James, Regulatory Affairs Manager for the MATL

project.

Instead, it intends to “clarify and restore what

was understood to be the law for over 100 years,”

said the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Ken Peterson, R-Billings.

That’s a misrepresentation, says John Vincent,

Gallatin County Public Service Commissioner and

a representative for IR-125. The eminent domain

law may be close to what it’s always been, Vincent

says, but with 198, the manner in

which eminent domain is acquired is

changed.

“Before [the new law] you could get

a permit from the [Department of

Environmental Quality], but that

didn’t give you eminent domain,” Vincent said.

“Under the law, you went to the landowner to see

if you could negotiate a deal—if not, you went to

the district court … Now, all you need is a certificate

of compliance from the DEQ.”

House Bill 198, abridged

An act clarifying a public utility’s power of eminent domain; clarifying

that a person issued a certificate under the Major Facility Siting Act

has the power of eminent domain; and providing an immediate effective

date and retroactive applicability date. Be it enacted by the

legislature of the State of Montana:

Section 1. Power of eminent domain. A public utility … may acquire

by eminent domain any interest in property, as provided in Title 70,

chapter 30 (the eminent domain law), for a public use authorized by

law to provide service to the customers of its regulated service.

Section 2. Power to exercise eminent domain. A person issued a

certificate pursuant to this chapter may acquire by eminent domain

any interest in property, as provided in Title 70, chapter 30, for a public

use authorized by law to construct a facility in accordance with the

certificate.

Section 6. Retroactive applicability. [Section 2] applies retroactively …

to certificates issued after Sept. 30, 2008.

Both sides agree that Montana, like all states,

needs an eminent domain law. They part ways

when it comes to how eminent domain should be

obtained by a private individual or corporation for

a private, for-profit project.

Most new high voltage transmission lines are

market lines built to sell more electricity in a

deregulated market rather than meet a public

need for power in a regulated market or service area,

Vincent said.

Proponents for the bill say the projects, many of which

propose utilizing wind power, are necessary for grid

stability and economic growth in Montana; plus, they

pay substantial state taxes and provide jobs.

“HB 198 is absolutely necessary if some of these projects

are going to go forward,” Peterson said.

Gov. Brian Schweitzer has called the bill “a deal with the

Devil.” He had announced an amendment prior to

the bill’s passing that would’ve required lawmakers to

address HB 198 again in 2013. But when

received the bill too late to amend it he instead let it

pass, saying it protected the economy and jobs.

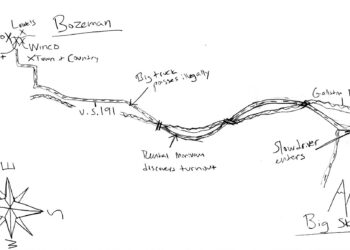

Proposed transmission line upgrade in Gallatin Canyon

Gallatin Canyon residents may soon be

impacted by 198, as well.

NorthWestern Energy is acquiring

property easements to upgrade the

69-kilovolt power line that runs south

from the Jackrabbit Substation, west

of Bozeman, down Highway 191, and

into Big Sky to a 161-kilovolt line.

The upgraded line is needed to support

development in Gallatin Canyon,

Big Sky and at the resorts, said John

Fitzpatrick, NorthWestern’s executive

director.

[dcs_img_left desc=”The 69-kV lines in Gallatin Canyon”

framed=”black” w=”250″ h=”135″]

https://www.explorebigsky.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/gallatin-canyon-lines-small.jpg[/dcs_img_left]

“Big Sky is one area that probably is

going to be more affected by eminent

domain than anyplace else in the North-

Western system in the short term,”

Fitzpatrick said.

If Northwestern lost the power of eminent

domain by having IR-125 pass,

Fitzpatrick says any landowner along

that project could shut it down, and Big Sky

wouldn’t get the needed upgrade in

services.

Property rights and IR-125

Both federal and state eminent domain

laws are designed to ensure that

landowners are given just compensation

if their property is acquired for

public use.

“Nobody wants to go through eminent

domain because of the cost and

time involved. It’s better to go talk to a

landowner,” Fitzpatrick said. “You have

to talk to landowners anyway… to give

them a final written offer.”

IR-125 is more about property rights

than about compensation.

“It wasn’t just about transmission lines,”

said Marie Garrison, the rancher from

Divide. “It was about who would want

to come in here and take our land. It’s

not right. It could be more than just the

power company; it could be anything.”

The right of Montana property owners

to have a level playing field when it

comes to eminent domain and condemnation

is too important to allow the automatic

‘trigger’ that a DEQ certificate

of approval provides private individuals

and corporations for private uses and

profit, commissioner Vincent said.

It’s about whether a corporation should

have the right of eminent domain and

the legal ability to condemn private

land for a private project whose primary

purpose is its own benefit and profit

rather than meeting an objectively

established public need.

The Major Facility

Siting Act

The DEQ uses the Major Facility Siting

Act (MFSA) to determine a project’s

worthiness, environmental compatibility,

public need and location.

The MFSA was developed in the 1970s

alongside the Montana Environmental

Policy Act (MEPA). It instituted a regulatory

and public engagement process

to review linear transmission, public

oil and gas facilities, energy generation,

coal fired power plants and nuclear

facilities.

Both Vincent and James pointed to

major problems in this process.

“Although the MFSA has criteria to

establish public need, they are, in practice,

virtually meaningless,” Vincent

said. He called the siting process a political

process disguised as an objective,

scientific, fact finding effort.

It’s been 40 years since the DEQ has

denied a certificate of approval, Vincent added. “They always

find a public need…because DEQ is

an executive agency and will always do

what the governor wants them to do.”

Vincent said that under former Gov.

Martz, the DEQ found a public need

justification for Holcim (the cement

supplier in Three Forks) to burn tires

for fuel in making cement. When

the DEQ’s data on air pollution from

burning tires was shown to be “virtually

baseless,” they forced to reverse its

decision.

“MFSA is a badly broken regulatory

tool,” said James from MATL. “It’s

confusing to the public, and [in the

case of transmission lines] it places

the state in the role of project developer,

rather than the objective role of

regulatory review… If we had a siting

process that worked, we wouldn’t be

embroiled in this eminent domain

debate to begin with.”

“It could work better,” said Tom Ring

from the DEQ’s Environmental Management

Bureau about the MFSA.

And policy changes are moving

forward. Under SB 206, a bill sponsored

by Sen. Llew Jones, R-Conrad,

the MFSA will now provide more

flexibility for landowners and project

developers.

Implications of repeal

If Montana voters repealed HB 198,

the 2013 Legislature would likely address

the eminent domain issue again.

Vincent hopes that under a new law,

private interests would be required—

both under the law and objective

public interest criteria—to prove that

a project benefits the public.

A repeal would have broad implications

on the regulatory process for

major projects like MATL and MSTI,

James says. Investor confidence may

suffer the biggest impact, he added.

Repeal could also drive up the cost

of energy bills statewide. As in the

case of the proposed Gallatin Canyon

power line upgrade, if a utilities

company like NorthWestern Energy

couldn’t exercise eminent domain

and ended up paying a high price on

legal negotiations or a new right-of-way,

all ratepayers would absorb that

extra cost.

Ideas for compromise are disparate.

Rep. Ken Peterson says the bill was

already a compromise, because they’d

had “substantial input from everyone

interested.” He doesn’t see any possibility

for future compromise.

James sees room for improvement in

the siting and environmental review

processes, the way the state engages

with landowners, and the way it responds

to landowner concerns as the

DEQ makes critical siting decisions.

“Before this bill was passed, we

already had a compromise in place

with the BLM and the DEQ and

NorthWestern Energy as far as line

placement,” said Marie Garrison. She

suggested placing the utility projects

on public lands.

“I make a choice to take care of my

kids,” Garrison added. “For them to

just come and slap this on our ground

would put extra stress on my life.

That’s why I got in the fight, because

I’m a very concerned mother.”