Lacking exclusive access to a helicopter and a specialized pilot, Gallatin County Sheriff Search and Rescue is forced to roll the dice in many critical emergencies

By Jack Reaney STAFF WRITER

On the morning of Aug. 16, 2022, Big Sky’s own Jeremy Blyth found himself caught in the midst of an unexpected rockfall.

He was climbing in Beehive Basin with Sam Felch, a trusted friend, ski patroller and fellow volunteer for Gallatin County Sheriff Search and Rescue. At the top of a three-pitch ascent between Middle and Bear basins, Blyth leaned against a massive rock flake; he estimates it weighed more than 500 pounds.

“It made a weird sound,” Blyth told EBS in a December phone interview. “I moved out of the way, and it slid—almost like an avalanche. [It was] a geological event which I happened to be around for.”

Unfortunately, Blyth also happened to be roped into that flake. He fell face forward behind the tumbling rock, managing to tuck and roll a few times as he bounced down the pitch, falling between 80 and 100 feet. The last couple bounces, he said, are where he really got messed up.

“I had two major breaks in my spinal cord, and a punctured lung—the other collapsed in surgery a day later,” he said. “I had two broken [shoulder blades], crushed T8 and crushed T12, severely separated ribs on both sides—they never me gave me a count—and I have a thoracic nerve issue. Oh, and I broke my elbow.”

Luckily, Blyth, who was wearing a helmet, sustained almost no head injuries. And he survived thanks to Felch’s initial, highly technical response, and a subsequent helicopter rescue from Gallatin County Sheriff Search and Rescue.

“I think they got to me in a little over an hour and performed a pretty crazy short-haul rescue. I was probably still 200 feet off the ground on a large cliff face. They quickly assessed that I needed to get the heck out of there pretty quick,” Blyth said.

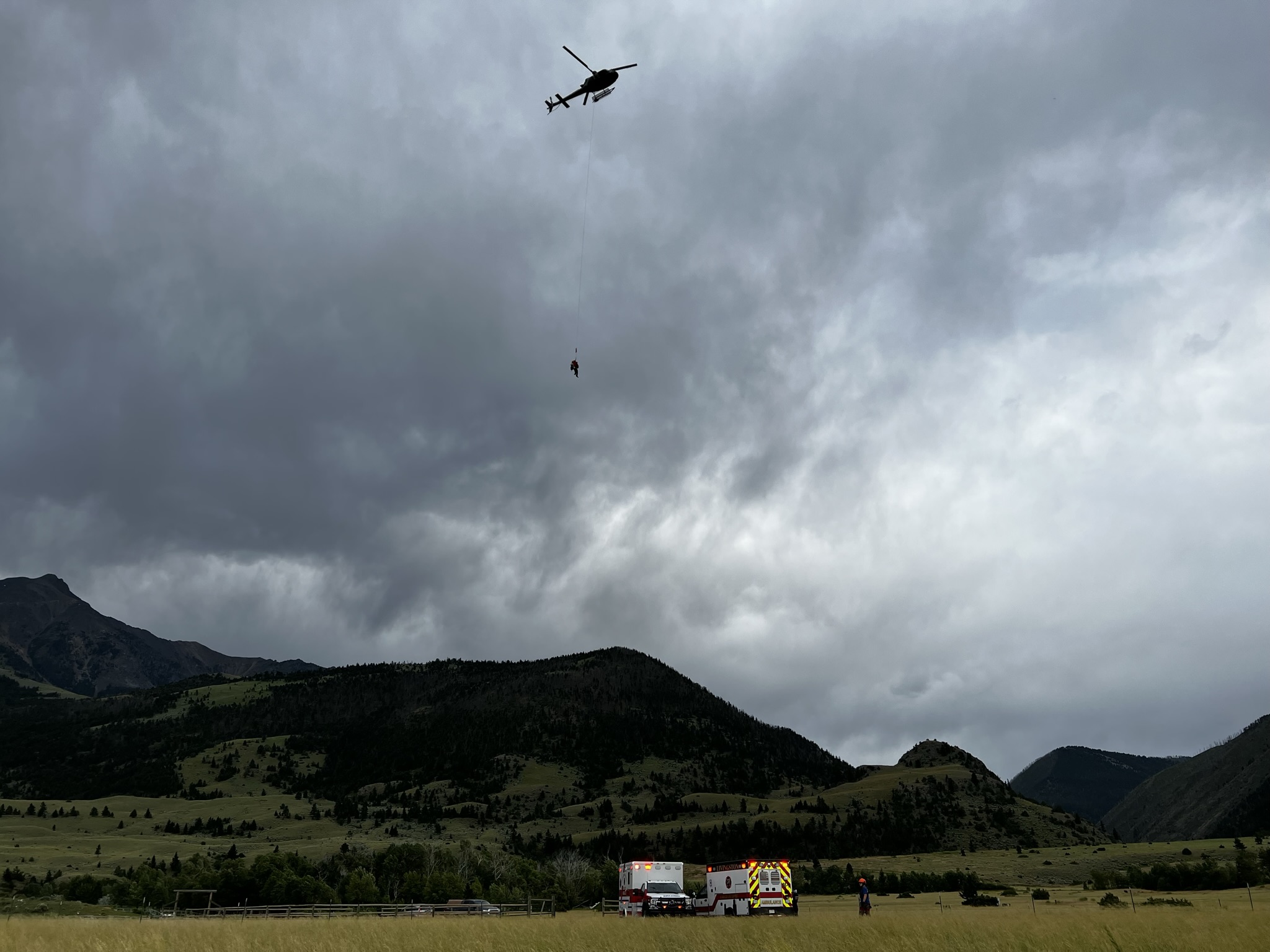

He was attached to a rope hanging from a helicopter, short-hauled to the nearby Big Sky Fire Station and transferred to a medical helicopter which airlifted him to Bozeman.

There’s no such thing as a typical helicopter rescue, but Blyth’s was an example of what it looks like when the volunteers of Gallatin County Sheriff Search and Rescue are called on a life-or-death mission.

While it sounds like a textbook case study of a successful short-haul rescue, it was mere coincidence that Gallatin County SAR had the capacity to rescue Blyth that day.

‘Varsity level in the world of helicopter flying’

“Any other day that week, [Jeremy] would have been sitting up there forever,” said Jason Revisky, training coordinator for Gallatin County Sheriff Search and Rescue. “It would have been a day—12-15 hours to get him out. In the condition he was in, he wasn’t gonna make it 12-15 hours.”

Revisky recalled that Mark Duffy, the helicopter pilot, had been gone for weeks on a fire in Idaho. But when Revisky called Duffy’s cell phone, he learned that Duffy had arrived in Bozeman the night before, for just one day. The pilot responded and short-hauled Blyth to safety.

Revisky and Mark Bradford, Big Sky section manager of GCSSAR, sat down with Explore Big Sky to discuss the challenges of short-haul rescue.

SAR programs don’t usually have helicopter rescue. Of those that do, there’s only one team in the entire United States that operates without an exclusive use contract—guaranteed access to a helicopter and a qualified pilot.

That would be Gallatin County Sheriff Search and Rescue, which serves backcountry enthusiasts around Bozeman, Big Sky, West Yellowstone and sometimes even the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness.

“We’ve been really fortunate—just kinda lucky—there’s nothing else to say,” Revisky said. “We’ve kind of survived up until this point. It’s only a matter of time until we’re going to have a rescue that’s screaming for short-haul—we’ve got to get this person out, it’s life and death—and we’re either not going to have a helicopter or not going to have a pilot. And that’s going to be that.”

When a wildfire catches or a remote medical emergency warrants a helicopter short-haul rescue, it’s no guarantee for Gallatin County SAR that either of two pilots, Duffy and Will Jacobs, will be available—or their helicopter. They are often away for extended periods, fighting wildfires beyond Montana and working construction and keeping sharp the skills they use to rescue hikers, hunters and climbers in the far reaches of Gallatin County.

In a short-haul maneuver, the rescuer attaches themselves and a packaged victim to a “long-line” cable dangling from a helicopter. The pilot then transports the rescuer and victim up to 8-9 miles to a safer location, often saving hours of critical rescue time.

“You’re looking at somebody [in a situation that’s] life or death, and they’re getting picked out of [a remote location] and in three minutes they’re in a life-flight helicopter,” Bradford said, describing one rescue on Granite Peak in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, where a hiker had broken his femur. “Otherwise, they’d be waiting hours and hours sitting and waiting to get carried down there to get into a helicopter.”

VIDEO COURTESY OF JASON REVISKY

“There’s such a giant problem that we have with our helicopter short-haul program,” Revisky explained. “The amount of challenges that we have with that program… I almost hate to talk about it because it gets depressing after a while. It’s such highly specialized work that requires an intense amount of training. To find pilots that can do it is nearly impossible.”

Revisky said a pilot with thousands upon thousands of hours flying a helicopter is not qualified for short-haul rescue.

“That’s the varsity level in the world of helicopter flying: Human external cargo,” Revisky said.

A pilot qualified for SAR needs flawless vertical reference, which only comes with thousands upon thousands of hours of long-line experience, Revisky said. He estimates that SAR pilot Mark Duffy has over 20,000 hours of long-line time.

“Mark Duffy did a lot of helicopter logging,” Bradford said. “Repetitively doing that, dropping that line and letting crews hook trees up.”

The typical long-line pilot might gain experience in Alaska, flying gear into remote locations for two years, Revisky said. Will Jacobs, the other qualified pilot, has been flying commercially for at least 15 years.

“It’s work. You don’t go to school to learn that,” he said. Furthermore, desirable pilots practice constantly, doing long-line work on construction projects, lumber work, firefighting, etc. You wouldn’t want to hire a pilot to be on-call for weeks without a rescue, according to Revisky.

“It’s like hiring a racecar driver that drives his car 12 times a year,” he said. “He’s not going to be a good racecar driver. It’s perishable skills.”

In the best form of an exclusive-use contract, Revisky and Bradford argue, there’s always a helicopter and a pilot on call for rescue work. Ideally, the team has more than two qualified pilots. When one pilot is on call for SAR, the other pilots are either taking time off or doing commercial long-line work, staying sharp and operating their business.

Without exclusive use, Gallatin County pays $3,300 per hour to Central Copters, a Belgrade company with other priorities that sometimes intervene with rescue work.

“We’ve kind of survived up until this point. It’s only a matter of time until we’re going to have a rescue that’s screaming for short-haul—we’ve got to get this person out, it’s life and death—and we’re either not going to have a helicopter or not going to have a pilot. And that’s going to be that.”

JASON REVISKY

Pilot and president of Central Copters, Duffy does everything from firefighting to ski lift and power line construction.

In a phone call, Duffy declined to comment on Central Copters’ involvement in SAR planning for an exclusive-use contract. He said that fundraising is a long process from start to finish.

On hiring more long-line pilots if needed, Duffy said, “that’s what we do. We’re in this business. It’s what we do for a living.”

Revisky said Gallatin County SAR is the only short-haul team in Montana. There isn’t one in Idaho or the Dakotas, and there’s only a small list of qualified pilots in the United States; Gallatin County SAR works with Duffy and Jacobs, down from four qualified pilots in the past.

A source of community insurance

Merely 200 miles south of Bozeman, however, a similar recreation destination’s SAR team has an exclusive-use contract throughout the winter, plus shared access with Grand Teton National Park and the U.S. Forest Service during the summer.

In Jackson, Wyoming, the short-haul system isn’t perfect; the Teton County Search and Rescue Foundation is raising money to purchase a helicopter and avoid wildfire conflicts during months of shared helicopter access. Still, Revisky and Bradford believe that the Gallatin County community could help SAR emulate the exclusive-use contract in Jackson, Wyoming.

The Teton County Search and Rescue Foundation depends on fundraising to pay for their exclusive-use contract. With seven full-time employees focused on fundraising, education and advocacy, TCSAR raises about $1.2 million per year.

“It would just be fabulous for [the Gallatin County] community if we could do something like that,” Revisky said.

Bradford believes that in Big Sky, the community would benefit from some balance between wildland firefighting and short-haul rescue capability.

He pointed out the expensive homes around Big Sky, including private communities in close proximity to wildfire risk. Consistent helicopter access could decrease insurance rates.

“They [could] have a helicopter on call, that in 15 minutes, can come dump a bucket of water on a lightning strike, or any type of fire that happens to be in the woods around here.”

Home protection is one key need for Big Sky. Even more unique is the disaster possibility created by Big Sky’s traffic bottleneck; with only one road from Big Sky to Bozeman, it’s not hard to imagine the advantage of a helicopter. Revisky gave an example:

“If [Big Sky Resort] ever has a big derailment of one of their ski lifts where lots of people get hurt, you’re going to want every helicopter resource you can get to get people out of here,” he said. “There’s only so much capability [in Big Sky] for medical care. They might need to go to Bozeman, or Billings, or Missoula. They need to get out of here.”

Flooding, people trapped on islands—any emergency when we would need it. There’s so much that could be done.”

In 2022, Gallatin County SAR has a budget of about $60,000 for short-haul missions. Revisky estimated that an exclusive-use contract would cost $1.2 million per year. That’s a substantial budget increase, so helicopter access is not going to be funded by tax dollars, he said.

“It could come from multiple sources,” Bradford said. “It is not going to be a tax levy we’re going after to get this money. We want the community to see the need, and to step up and fund this need.”

‘Not a broken system’

Revisky emphasized that Gallatin County Sheriff SAR is not a broken system.

He described the volunteers as incredible, dedicated and skilled—sometimes working from dusk to dawn on dangerous rescue missions and sacrificing hours of free time they might rather spend with family or adventuring in the backcountry themselves.

“Exclusive short-haul would just be another tool in our toolbox,” Revisky said.

After he clipped onto a rope and dangled beneath a helicopter to save a critically injured Jeremy Blyth, a Big Sky resident and fellow SAR volunteer, it’s not hard to imagine why Revisky is fighting for a consistent toolbox.

Blyth has 14 screws in his back, and bars holding them together. He hopes to have those removed in about a year. Doctors told him he can be physically active as long as he doesn’t fall. Less than four months after a fall that should have killed him, Blyth said he might go cross country skiing.

“The fact that I can walk is pretty astounding at this point,” he said. “I credit the availability of the helicopter with my life, and the skills of the pilot—which are astounding.”

Lying injured on a cliff face, still 200 feet above the ground, Blyth believes a rescue by hand would not have gotten him out of Beehive Basin before nightfall.

“It was just a difference of an hour or two between me having a pilot and living, and me dying,” he said. “It’s pretty important to my life, having a helicopter.”

PLUS: Jeremy Blyth sat down with the Hoary Marmot Podcast, newly partnered with EBS. Hear Blyth’s firsthand account of the accident and how Gallatin County SAR saved his life, and how Bradford and Revisky went on a mission to notify Jeremy’s wife Miriam as she was backpacking off the grid.