Fred F. Willson’s legacy lives on through some of Bozeman’s oldest buildings

By Mira Brody EBS STAFF

BOZEMAN – From the top of the new Armory Hotel in downtown Bozeman, the tallest building in town at nine stories, you can spot many of Fred Fielding Willson’s architecture, including one of the most iconic, filling most of your western view: the Baxter Hotel, its 11 glowing red letters and the infamous Bridger Beacon nestled just below.

Others include the Gallatin County Courthouse, the Emerson, Longfellow School, countless houses of varying elegance and style in the Historic District, and the first two floors of the Armory itself. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to stand anywhere within a two-mile radius of downtown and not spot a building designed by Willson.

When it first opened in 1941, the Armory at 24 W. Mendenhall St. housed the 163rd Infantry Regiment of the Montana National Guard during World War II, complete with a rifle range, soundproof room and thick floors capable of accommodating military trucks and tanks.

The contractors and hotel, an operation of the Kimpton Hotel and Restaurant Group based in San Francisco, pays homage to the building’s legacy and the history of the area, as well as Willson’s artistic mind and the visions he had for the city of Bozeman.

Aaron Whitten, the Armory Hotel’s general manager, knows some of the many hats the building has worn over the years.

“I’ve heard stories here from prom being hosted here, to a taco shop getting their start here, to jazzercise. So this space has lived quite a few lives since that original 1941 Armory,” Whitten said. “To speak to how the space reflects in the community, everyone that I’ve talked to in town has a story or connection or an experience with this particular building in one capacity or another.”

Walking through the hotel’s second floor on the mezzanine above the stage offers slices of its past, literally. The building’s designers opted to reveal pieces of the concrete walls as a tribute. The concrete used in the WWII-era was speckled with pieces of stone, wood and rebar, making for a sort of industrialized mosaic.

The dance floor below, once used for tank maneuvers, looks on toward an impressive stage that will, as soon as revelers can gather again, host performances for a room of up to 600 people. The restaurant, appropriately named Fielding’s after Willson’s middle name, is a step back in time to traditional American cooking and dining.

Born in 1877 in Bozeman, Willson had a heritage worthy of making any native Montanan proud. He attended the town’s public schools as well as the Bozeman Academy and Montana State College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts before graduating with a bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Columbia University in New York. He traveled around Europe to further his architectural education, visiting several countries including France, Germany, Italy and Britain, and studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. His diary entries during this time document his impressions of European architecture and lifestyle during the early 20th century.

It was in January of 1910 that Willson returned to his hometown for good, bringing with him the inspiration collected from his travels that now mark the neighborhoods of Bozeman. These influences are revealed in his designs, which include multiple architectural styles: Georgian, Mission Revival, Art Deco and Craftsman.

Juxtaposing the Armory’s masculinity and bold art deco style are pieces of its female ancestry as well. After all, it was Etha Story, the daughter-in-law of another Bozeman pioneer Nelson Story, who raised the funds that were donated to procure the land where the Armory was built.

Armory staff worked alongside Susan Denson-Guy, executive director of the Emerson Center for Arts and Culture, to curate unique and custom fine art pieces for the interior. Among those artists are Vicki Fish, Will Hunter and DG House, who painted a one-of-a-kind “Armory Bear” for the hotel’s Green Room.

“It’s really, really special that we were able to connect with such passionate artists in the area,” Whitten said. “The art and space were inspired by each other.”

While Willson believed in functionality, he was also a strong believer in art and the beauty that architecture has the power to bring a community.

“There is a fundamental reason for every feature embodied in a structure,” Willson said in a 1954 address at Montana State University, two years before his death. “It must have refinement, simplicity, beauty and good taste. Thus an architect’s business is to make the things of daily life beautiful.”

On the ninth floor rooftop, the historical aspect of the building becomes a bit muddled, what with the rooftop pool and glass walls, but in the the basement you can get a stronger taste for what the original Armory was nearly 80 years ago. The underground whiskey bar, Tune Up, is housed down here, where the infantry’s band would practice in the ‘40s.

“… an architect’s business is to make the things of daily life beautiful.”

Fred F. Willson

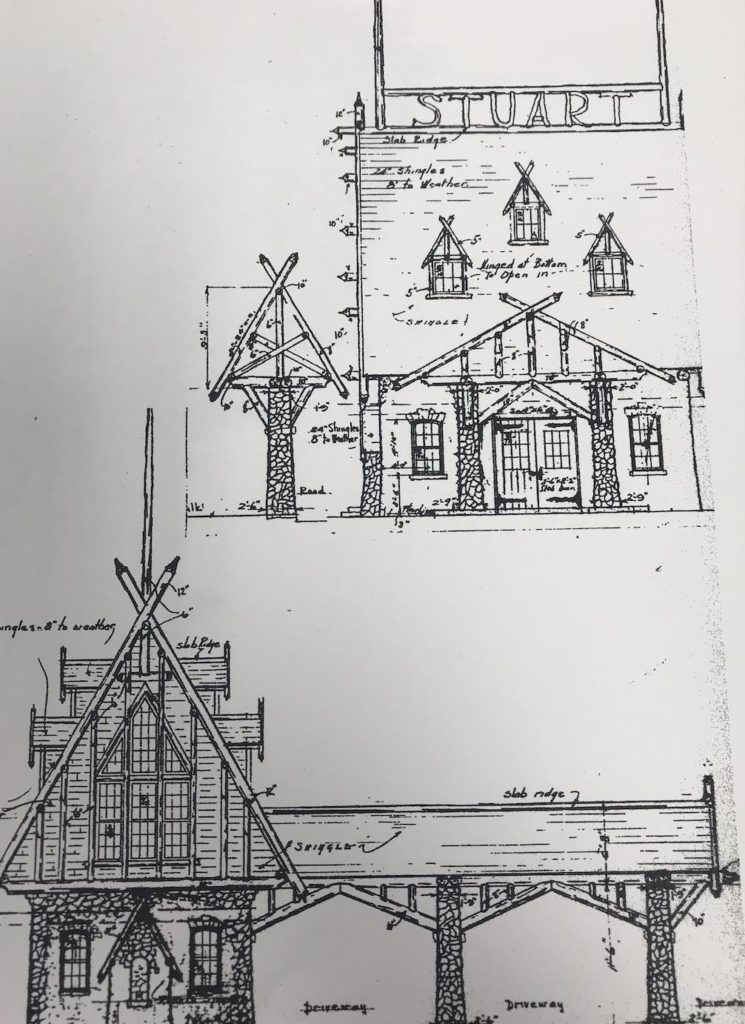

Just outside of Tune Up, two large, original metal light fixtures hang like sentries on either side of the entrance under a metal, art-deco-style awning that wasn’t part of the early building, but did actually appear in Willson’s early blueprints. It’s unnerving to think that at one time the Armory was slated for demolition and was only revived after a decade of paperwork, permits, meetings, construction and construction stoppages.

“There’s a few components of the exterior that are actually brought to life, rendered from notes that Fred took originally in his architectural drawings,” Whitten said. “Essentially we saw in the margins components that are now functional and alive.”

Even standing at street level before the massive structure, its chrome chevrons pointing toward the sun with a backdrop of the city’s bustling downtown, you can still catch sight of, without much effort, Willson’s work and the legacy he left behind in the Gallatin Valley.