Managing chronic wasting disease in the Greater Yellowstone

Part 1: Lay of the land

By Jessianne Castle EBS ENVIRONMENTAL & OUTDOORS EDITOR

As the deadly wildlife disease known as chronic wasting disease, or CWD, spreads into Montana, EBS is looking closely at what that means for the Greater Yellowstone Region and how wildlife managers will respond. This is the first in a series about CWD in Montana.

LIVINGSTON – Emily Almberg, the state’s disease ecologist for Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, is vexed by a growing dilemma. The neurological disorder known as chronic wasting disease, found in deer, elk, moose and caribou, has population-level impacts on wildlife herds. Asymptomatic in its early stages but ultimately fatal, CWD can survive in the soil and remain infectious for a yet unknown length of time. There’s no live-animal test. And thus far, we still don’t know if humans can get it

Sometimes called “zombie deer disease,” the ailment causes stumbling, lethargy and weight loss in its advanced stages. It is caused by prions—misfolded, naturally occurring proteins—normally found in the central nervous system. As the prions build up, they cause a Swiss cheese effect in the nervous system—literally resulting in holes in the brain and degeneration to the point of death.

As test results rolled in at the close of 2019 and early 2020, wildlife managers watched the positive toll tick steadily up in wild herds. Around the same time, the Montana Department of Livestock reported a positive result from a game farm in eastern Montana. The facility is now under quarantine while DOL investigates.

CWD showed up in Montana for the first time in the wild in 2017, and as it continues to pop up in new areas, state wildlife officials are transitioning their practices and considering how things will change if the disease is here to stay.

A dilemma

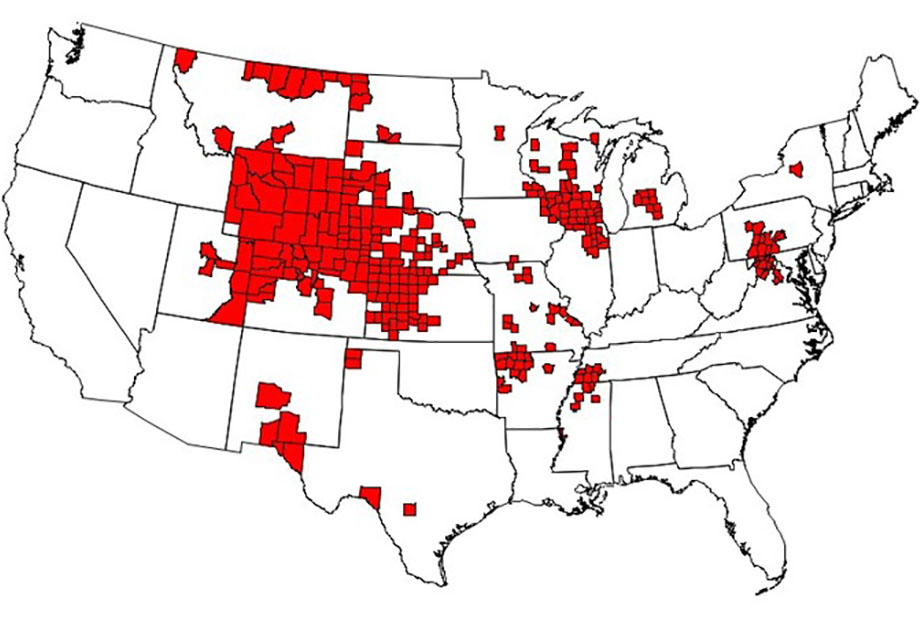

Montana biologists tested 6,977 deer, elk and moose for CWD in 2019. It’s a record number of tested animals, and has led to a record number of positive samples: 142. While our neighbors to the north in Alberta and to the south in Wyoming and Colorado have dealt with the disease for decades, the Treasure State has only begun to manage for CWD since finding the disease in the wild in 2017.

Colorado State University scientists identified the illness for the first time in 1967 in a research mule deer herd in Colorado. At the time, the world had never seen the impacts of the disease in deer or elk, though a similar disease known as scrapies has periodically ravaged domestic sheep herds since the 18th century. CWD and scrapies belong to a class of disease known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, TSE, or sponge-like degeneration. Among its brethren are mad cow disease, which infected the British beef industry in the early 1990s, and Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease in humans. While the common denominator for all TSEs is the fact that prions cause holes in the brain, it appears the diseases can be species-specific. In the case of CWD, so far it has only infected the deer family, but lab studies about transmission across species remains inconclusive.

By the late ’70s and early ’80s, researchers found CWD in captive facilities in Toronto, Colorado and Wyoming, and in 1981 it was documented in Colorado’s wild elk. After wild mule deer in Colorado and Wyoming began testing positive for CWD in 1985, MT FWP began surveillance efforts in the mid ’90s.

In the late ’90s, elk tested positive at a captive game farm in Phillipsburg southeast of Missoula, the only blemish on Montana’s pre-2017 record. Livestock officials with the Montana Department of Livestock killed the herd, burned the carcasses and facility equipment, and the game farm closed. CWD hasn’t been found in the area since, but its presence on a game farm worried managers.

Since Montana documented CWD in Phillipsburg, the state’s CWD monitoring in wild populations has undulated with the flow of federal dollars to support the cost of testing, with a focus on high-risk areas along the state’s northern and southern borders, and near Phillipsburg. Meanwhile, the disease appeared in the early 2000s on a game farm in South Korea and in free-ranging Norwegian reindeer in 2016.

While test results stream in across the nation, wildlife managers and disease specialists are strapped for a solution. “We don’t have a lot of options right now in terms of trying to manage [CWD],” said Jonathan Mawdsley, a science advisor for the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, during a panel discussion on CWD held in Bozeman in 2018.

“Removing the disease agent is incredibly difficult,” Mawdsley said, explaining that toxic compounds like lye or bleach have been used with some success to destroy the prion, but because it is a protein and not a living organism the disease agent can’t just be killed—it has to be destroyed. Scientists still don’t know how long CWD remains infectious in the ground, but Mawdsley said scrapies has been found to survive for 16 years.

New positives

When the dreaded positive result arrived in Montana in 2017 from a test center at Colorado State University, MT FWP ramped up its surveillance efforts. In 2019, the agency offered free statewide testing to hunters for the first time to aid surveillance and of the 6,977 samples, about 15 percent were submitted by hunters from across the state.

“[Statewide testing] gave us a glimpse into populations across the state,” said Almberg, the MT FWP disease ecologist. “In many places we didn’t get enough samples to say it was absent, but we did get a bunch of new positives that we probably would not have found otherwise, at least not really soon.”

Among those samples hunters voluntarily submitted were three that came somewhat as a surprise. MT FWP found the disease in 2017 in wild animals, but hadn’t since detected it in species other than mule deer and whitetails. However, in November a hunter-harvested moose near Libby in the northwest corner of the state tested positive, as did an elk killed on private land northeast of Red Lodge. Then, in December, first case of CWD in Southwest Montana was confirmed in a white-tailed deer in the Ruby Valley near Sheridan.

“That paints a pretty different picture of CWD in the state than even just a year ago,” Almberg said. “It’s more widespread than we thought.”

The percentage of animals infected varies from less than 1 percent to as high as 7 percent in mule deer, depending on the area, and up to 4 percent in white-tailed deer. In Libby, which has a large urban deer population, up to 13 percent of deer have the disease.

Learning from others

Scott Talbott witnessed the perplexity of CWD in Wyoming’s wild deer and elk herds for the entirety of his 34-year career. The former director of Wyoming Game and Fish, Talbott retired at the beginning of 2019. When he spoke during the Bozeman CWD panel in 2018, he still led the agency.

“All of us face our own unique set of circumstances when it comes to this disease,” he said to the audience of mainly journalists and outdoor writers. “It’s interesting to me how little is actually known, not only by agency people, but going out and talking to the public.”

Talbott said Wyoming’s attempts to eradicate infected small herds were unsuccessful, and the disease has continued spreading. With the prion able to sustain itself in the soil, CWD is conflagrated further by wildlife moving around on the landscape, often over long distances. He cited studies in Wyoming indicating mule deer migrate in excess of 250 miles from central Wyoming up into Idaho annually.

“When you look at those migrations into and out of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, into and out of Colorado as well, the implications for the movement of that disease naturally are pretty significant,” Talbott said.

Biologists in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks opportunistically test for CWD in roadkill and at predation sites. All results in Yellowstone have so far been negative, but a roadkill mule deer buck from Grand Teton tested positive for CWD in 2018.

The Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies in 2018 released recommendations on how to reduce the spread of CWD. Among them is the need for reducing artificial concentrations of wildlife.

Wyoming has the largest complex of feedgrounds on the continent, supporting elk at the National Elk Refuge in Jackson Hole and at 22 state-run feedgrounds in other parts of the state. Wild elk have used these sites where wildlife managers supply hay in the wintertime for more than a century, and according to Hank Edwards, the Wyoming Game and Fish Wildlife Health Laboratory supervisor, you can’t just stop the feeding overnight.

“The feedgrounds are incredibly complex,” he said, describing the animals’ dependence on the feed and the number of stakeholders and livelihoods affected by the feedgrounds, which draw tourists each winter.

Wyoming has largely taken what some critics call a reactive approach to CWD. “We have proven what happens if you don’t do anything,” Edwards said. “It’s sobering. We have a lot of CWD.”

He added that Wyoming is seeing an effect on wildlife herds. Researchers don’t know why, but deer tend to be the most susceptible, and bucks are hit harder than does. Edwards said Wyoming has some deer populations that are experiencing 50 percent prevalence and are experiencing a decrease in the number of older bucks.

Edwards mentioned Wyoming’s work to create a new management plan, which would identify ways his department could try reducing the disease’s spread. The Wyoming Game and Fish Commission is slated to hear the proposal in March, which will be available for public review before final approval.

As Wyoming takes a hard look at how it is going to respond, so too is Montana. A citizen panel and agency working group are working to revise the state’s current management plan, which the Montana Fish and Game Commission will consider in April, before opening a public review process.

Additionally, various entities are looking to get to the bottom of the science of CWD, considering how the disease spreads across the landscape, whether it can spread to other species, and the potential impacts of predators.

Read the next edition of EBS to learn more about CWD in the Greater Yellowstone.