Uncategorized

Reliving the Siege of Leningrad

Published

11 years agoon

By Emily Wolfe Explore Big Sky Managing Editor

The 2.5 million people trapped in the city endured starvation, disease, extreme cold, daily bombings and saw death en masse for 872 days during the Siege of Leningrad.

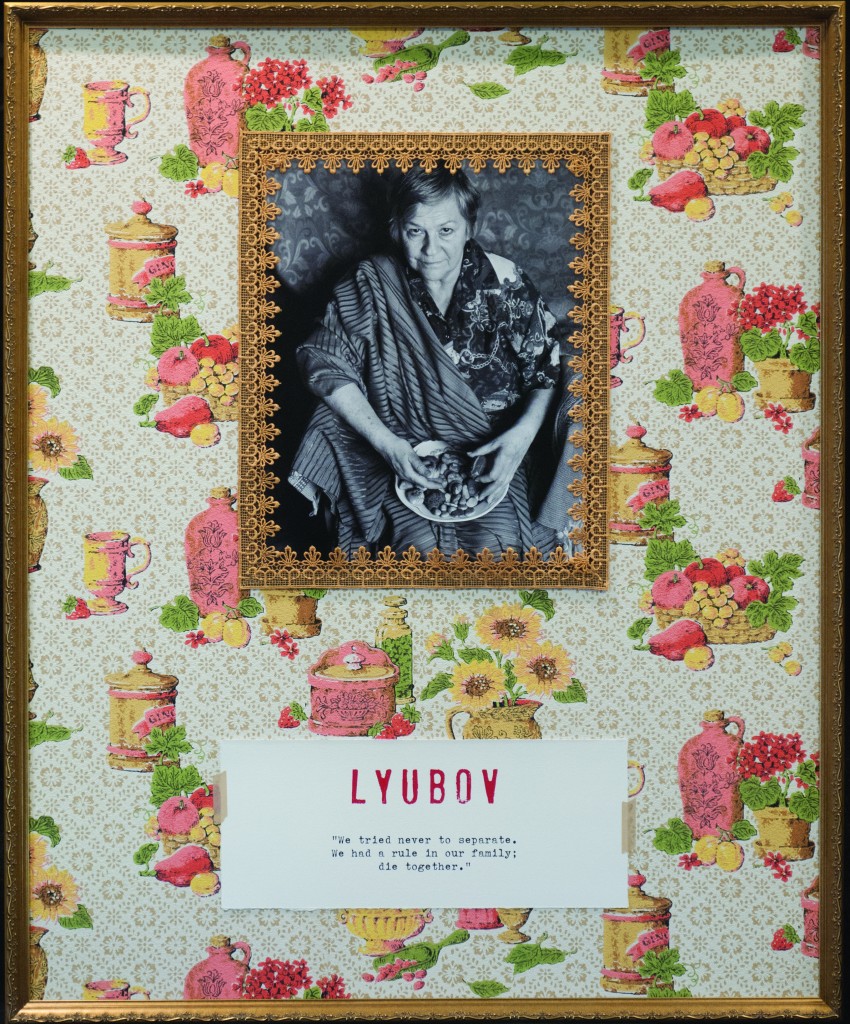

One survivor, Lyubov, said even through the horrors, she witnessed theft only once during those 2 ½ years, when a man tried to take food from a 6-year-old boy. “I saw him do it,” she told photographer Jill Bough of the incident that happened more than 70 years ago. “And then right there, in a quick moment, he stepped back and covered his face with shame.”

Bough, 46 and a resident of Big Sky, spent the last eight years photographing women like Lyubov who survived the siege, a World War II blockade during which German and Finnish troops attacked Leningrad, a once thriving industrial center. Refusing to surrender, the citizens had limited access to food, fuel, heat, water and electricity from September 1941 to January 1944. An estimated 1 million people died, and most were buried in mass graves.

Lyubov, who was a young girl during the siege, told Bough her family tried never to separate. “We had a rule in our family; die together.”

Because most of the men were killed on the front lines, the majority of the survivors today are women in their 80s like Lyubov. Known in Russia as “Blokadnitsa” – literally translated as a woman who survived the blockade – many of these women never spoke of the siege, enduring a lifetime of guilt and stigma associated with the terrible things they had to do to survive.

Trained as a journalist and a photographer, Bough is a Montana native who has lived in Moscow and St. Petersburg (the name for Leningrad prior to 1924 and after 1991). She did two previous photo projects in Russia – “Russian Women I Admire” and “The Russian Heart, Scenes from a Village,” but didn’t initially realize the complexity of “The Blokadnitsy Project.”

“[At first] I thought they were heroic and would want their story to be told, and it turned out they were embarrassed and ashamed,” she said, explaining that the women were often distrustful of foreigners and fearful of the government.

Eventually, Bough befriended Galina, a Blokadnitsa who slowly introduced her to others (pictured at right with Bough’s daughter Jessie). To gain their trust, Bough spent many hours with each, accepting the requisite tea, vodka and sweet cakes, and photographing items in the apartments.

Eventually, Bough befriended Galina, a Blokadnitsa who slowly introduced her to others (pictured at right with Bough’s daughter Jessie). To gain their trust, Bough spent many hours with each, accepting the requisite tea, vodka and sweet cakes, and photographing items in the apartments.

She always brought an assistant – sometimes her children, who are fluent in Russian – to help with lighting and translation. It also helped to make a personal connection with the women, she said. “That really was the hardest part of the project.”

Finally by afternoon, Bough said, the memories of the siege would emerge. Family members who’d never heard them came to listen.

“Every one of them, [had] stories about passing a frozen corpse on the street holding a live baby and not picking up the baby,” Bough said. “All talked about feeling jealousy toward a brother, wanting their brother to die so they could get his food ration.”

The project was at times so difficult and painful that Bough questioned her own intentions, but even so, she felt compelled to continue.

In 2012, Harvard (her husband Loren’s alma mater) asked if she’d do a show, so she put together an exhibit of photos and books focusing on 12 of the 25 Blokadnitsy she interviewed that showed at Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies in November 2013.

Bough shot the black and white portraits on a medium-format film camera and framed them with brittle, vintage Russian lace or wallpaper, an attempt to bring the viewer into the women’s apartments. Printed large, the images have a sense of weighty stillness, every etched wrinkle on the women’s faces suggesting a lifetime beyond the single frame.

“It was the process and the experience of meeting these women that became the art,” she said, something that’s evident in the books she created to accompany the photographs.

Bough worked with Bozeman artists Molly Merica and Priscilla Foster to make the handmade, collage-style books with old photos and Bough’s own images of the details and memorabilia in each apartment. In them, she recounts the memories of the Blokadnitsy – harsh, sometimes unemotional, and terrifying.

“The official perspective on the blockade is that it was a very heroic [act] from the people, and they suffered a tremendous amount but they never gave in. Soviet and Russian historical narratives focus on the magnificent accomplishment, which of course it was,” said Alexandra Vacroux, Executive Director of the Davis Center.

“What Jill is [portraying] is the face of what had to happen in order to have that accomplishment,” Vacroux said. “It’s not that convenient a part of the official narrative to focus more on the suffering and the pain and the agony that people went through.”

“In a way when you glorify the people that survive, you do at the expense of their story.”

Bough plans to donate her books to the Harvard Library, but emphasizes she isn’t a historian, and that her own feelings and opinions are part of the translations, photography and stories.

“I asked [Lyubov] if she and her mother often talked about this time period,” Bough wrote in one of the books. “‘Oh, no.” she says. ‘We never once spoke about the siege. I feel confused and sorry for the questions that have no answers. Six people in our family died of hunger during those three years; and it’s as if it never happened at all.”

Bough was hesitant to show The Blokadnitsy Project in St. Petersburg, but says she knows she will.

“In the end I think I realized – and I’m still back and forth on it – it’s a time period that needs to be remembered… There’s a reason they were willing to meet with me and told me those horrific stories… I think they want their experience to be known, and maybe in this late time in their [lives], they understand they were never at fault, they were victims.”

“The Blokadnitsy Project” will be on exhibit in the Warren Miller Performing Arts Center gallery, where Bough is on the board, from Feb. 12-26. On Feb. 16 she will host an opening reception from 5-6:30 p.m., with Russian appetizers and wine, and a 30-minute lecture and Q & A session at 5:30. The opening is free and open to the public. Find more of Bough’s work at jillboughphoto.com.

Megan Paulson is the Co-Founder and Chief Operating Officer of Outlaw Partners.

Upcoming Events

november, 2024

Event Type :

All

All

Arts

Education

Music

Other

Sports

Event Details

Spanish Classes with World Language InitiativeThese unique, no cost Spanish classes are made possible by the contribution of Yellowstone Club

more

Event Details

Spanish Classes with World Language InitiativeThese unique, no cost Spanish classes are made possible by the contribution of Yellowstone Club Community Foundation (YCCF) and Moonlight Community Foundation (MCF). This class will focus on building a lifelong affinity for world languages and cultures through dynamic and immersive Communicative Language teaching models.

Beginner Class – Mondays and Wednesdays from 5:30-6:30 pm

Intermediate Class – Mondays and Wednesdays from 6:45- 7:45 pm

- Classes begin Oct.7, 2024 and run for 6 weeks

- Class size is limited to 12 students

- Classes are held in Big Sky at the Big Sky Medical Center in the Community Room

For more information or to register follow the link below or at info@wlimt.org.

Time

October 21 (Monday) 5:30 pm - November 27 (Wednesday) 7:45 pm

Location

Big Sky Medical Center - Community Room (2nd Floor)

Big Sky Medical Center - Community Room (2nd Floor)

Event Details

Spanish Classes with World Language InitiativeThese unique, no cost Spanish classes are made possible by the contribution of Yellowstone Club

more

Event Details

Spanish Classes with World Language InitiativeThese unique, no cost Spanish classes are made possible by the contribution of Yellowstone Club Community Foundation (YCCF) and Moonlight Community Foundation (MCF). This class will focus on building a lifelong affinity for world languages and cultures through dynamic and immersive Communicative Language teaching models.

Beginner Class – Mondays and Wednesdays from 5:30-6:30 pm

Intermediate Class – Mondays and Wednesdays from 6:45- 7:45 pm

- Classes begin Oct.7, 2024 and run for 6 weeks

- Class size is limited to 12 students

- Classes are held in Big Sky at the Big Sky Medical Center in the Community Room

For more information or to register follow the link below or at info@wlimt.org.

Time

October 28 (Monday) 5:30 pm - December 4 (Wednesday) 7:45 pm

Location

Big Sky Medical Center - Community Room (2nd Floor)

Big Sky Medical Center - Community Room (2nd Floor)

Event Details

Spanish Classes with World Language InitiativeThese unique, no cost Spanish classes are made possible by the contribution of Yellowstone Club

more

Event Details

Spanish Classes with World Language InitiativeThese unique, no cost Spanish classes are made possible by the contribution of Yellowstone Club Community Foundation (YCCF) and Moonlight Community Foundation (MCF). This class will focus on building a lifelong affinity for world languages and cultures through dynamic and immersive Communicative Language teaching models.

Beginner Class – Mondays and Wednesdays from 5:30-6:30 pm

Intermediate Class – Mondays and Wednesdays from 6:45- 7:45 pm

- Classes begin Oct.7, 2024 and run for 6 weeks

- Class size is limited to 12 students

- Classes are held in Big Sky at the Big Sky Medical Center in the Community Room

For more information or to register follow the link below or at info@wlimt.org.

Time

November 4 (Monday) 5:30 pm - December 11 (Wednesday) 7:45 pm

Location

Big Sky Medical Center - Community Room (2nd Floor)

Big Sky Medical Center - Community Room (2nd Floor)