Gallatin Canyon sewer project appears feasible, must scale funding and earn DEQ permit

By Jack Reaney ASSOCIATE EDITOR

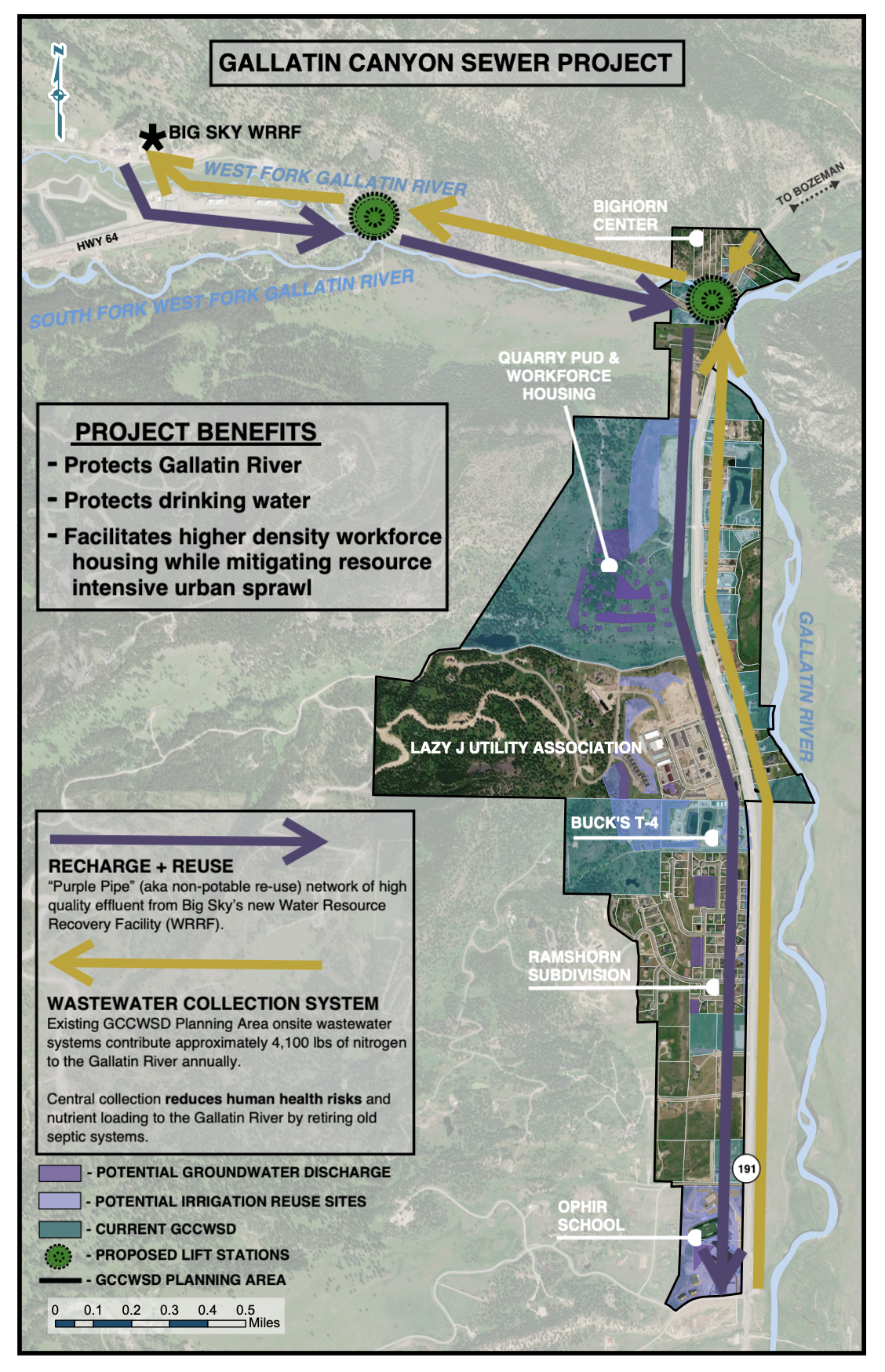

If things go according to plan for the nascent Gallatin Canyon County Water and Sewer District, a significant share of Big Sky properties along U.S. Highway 191 near the Gallatin River will disconnect from existing septic systems and connect to a centralized sewer.

That sewer would pump wastewater to Big Sky’s new Water Resource Recovery Facility, which yields virtually drinkable, Class A-1 effluent. Proponents say the treatment upgrade would result in a net benefit to the Gallatin River, even accounting for residential and commercial development that the canyon sewer district could enable.

Mace Mangold, VP of infrastructure for WGM Group—the engineering firm contracted by the district—said the potential for more development is the biggest point of community pushback he’s heard.

“And that is true, but I’d also argue that new development will happen regardless of central sewer, and that this is our opportunity to use new development to solve old problems,” Mangold said.

The old problems? The vast majority of septic systems do a relatively poor job removing pollutants from wastewater—the Gallatin River is officially “impaired” and studies are underway to determine the potential negative impact of nutrients found in wastewater like phosphorus and nitrogen.

Kristin Gardner, chief executive and science officer of the Gallatin River Task Force, told EBS the nonprofit is very supportive of the project.

“It’s such a huge benefit. I think it’s the most impactful project that we could do to address the water quality issues that we’re seeing in the Gallatin,” she said.

Aside from replacing old septic systems and eliminating the need for new ones, a centralized sewer would also serve as a release valve for the new WRRF. The Big Sky County Water and Sewer District could return surpluses of its effluent—reclaimed water not used for irrigation or snowmaking—for discharge into underlying Gallatin Canyon aquifers.

Although discharging into aquifers may sound concerning, Gardner said it’s a huge upgrade; the centralized, two-way sewer could reduce nitrogen output by a factor of ten, also reinforcing against increasing drought patterns.

“Septic systems are putting in wastewater that has [nitrogen] concentrations of 50 milligrams per liter, and we’re talking about a decrease to five [milligrams],” Gardner said. Phosphorus would drop near zero, from roughly 10 milligrams per liter in septic output.

“It’s a benefit. It’s an asset, rather than a liability,” she added.

In May 2020, GRTF commissioned a preliminary feasibility study and another in July 2021 to identify areas of highest impact, in support of the canyon sewer district, which was established in December 2020.

Johnny O’Connor, general manager of the Big Sky County Water and Sewer District, endorsed the project in a July letter to the Big Sky Resort Area District board. O’Connor told EBS that BSCWSD’s goal is to be proactive in protecting the Gallatin River before ever being told to clean up by a regulatory agency. Cost inflation does not override that goal.

“We’re building, essentially, a whole new infrastructure to take degraded and outdated systems off-line. And we’re—as a community—looking forward to getting this [sewer], so we’re not influencing the Gallatin River,” O’Connor explained. “Doing our due diligence and being good stewards of our environment—that’s the crux of the partnership.”

Three hurdles to feasibility

On July 10, the project reached a milestone as O’Connor and the BSRAD board endorsed its feasibility—despite ballooning costs since its initial estimate in 2020—concluding a near two-year effort to evaluate three challenges.

First, whether Montana Department of Environmental Quality will issue a discharge permit when the district applies in August.

“We landed on yes,” Mangold said. “We’ve got DEQ support for the project, they like the project, and it’s just navigating all the elements to get to a discharge permit.”

In September 2023, DEQ Water Quality Division Policy Analyst Eric Sivers wrote a letter to the district confirming the project appeared feasible, answering a request from the district to help secure funding.

In July 2024, a DEQ spokesperson responded to EBS with a written statement regarding the agency’s stance on the project.

“DEQ will begin the process of evaluating engineering plans, reviewing a discharge application, and developing a position once the district finalizes and submits the required application materials.

“The department generally promotes higher levels of treatment and connections of onsite systems to centralized treatment to reduce watershed nutrient loading. This goes for any of the state’s watersheds,” the spokesperson stated.

The second challenge is a choice: to stomach the increasingly expensive and complicated construction of sewer infrastructure along Montana Highway 64, or to build an independent wastewater treatment facility in the canyon.

The former is the original plan and will cost roughly double the $12 million forecasted in 2020, which BSRAD committed to fund with its additional “1% for infrastructure” resort tax. Mangold said it will now cost between $20 and $25 million to build pipes and lift stations to pump wastewater uphill to the WRRF, and that cost will likely keep rising.

“We’re comfortable with those challenges… working with MDT, working with the Forest Service, and potentially working with some landowners to get all that connected. But landed on yes, we can do that,” Mangold said.

Plan B is also feasible. But both water and sewer districts, and BSRAD, remain engaged in “the co-solution as the best solution,” Mangold said. It could create a $5 to $10 million benefit for both districts, and O’Connor said it would cost more in the long run to separately build an inferior and less durable treatment plant.

Third, the biggest challenge is overall economic feasibility. The entire project will cost at least $50 million and will require widespread buy-in from property owners and developers.

The first phase—and likely the minimum viable—would include the northern half of the corridor, between the 191/64 intersection and Buck’s T-4. Mangold said that’s the bulk of the entire district, including parcels located east of the highway beside the sensitive Gallatin River.

Eventually, if the sewer expands further south toward the Big Sky School District and Riverhouse BBQ and Events, overall cost would be roughly $70 million. Mangold said building a central sewer is an economy of scale—the more buy-in, the more affordable it becomes.

To achieve buy-in, the biggest hurdle will be reducing connection fees. Especially in existing developments like the Ramshorn View subdivision—just south of the initial phase boundary—where septic is already a sunk cost to property owners, the district will need funding to subsidize connection fees. To annex Ramshorn into the district, a 75% majority of homeowners association members would need to vote in support.

“It’s tough for a Ramshorn-type owner to get to a ‘yes’ there,” Mangold said. “No fault of their own, it’s just free versus paying a bill.”

In the past six months, the district has gained support from property owners in the northern half of the corridor.

Scott Altman, president of the canyon sewer district, believes that first phase includes the most important parcels to annex for the district’s mission of benefitting river health.

“We really want to replace those septic systems with [centralized sewer] that is really going to help the whole canyon,” Altman said.

Solution may be handcuffed to development

In addition to his role with the district, Altman is a leading developer in a large-scale planned unit development, the Quarry, that would largely fund the initial sewer implementation and benefit from its existence—full build would likely not occur until the sewer goes live.

As planned, the Quarry includes 135 single-family homes, 130 apartments, and commercial spaces. It has stirred up environmental concerns due to the uncertainty of the sewer project—two phases have already been approved for construction using high-tech septic systems as a stopgap until the sewer is ready, but if the sewer falls through, activists say septic will be detrimental in the long term.

Altman said the Quarry will pay for a significant part of sewer construction, in addition to providing a large customer base to sustain the district.

In the best-case scenario, the sewer project would come together quickly, and the Quarry can avoid building temporary septic infrastructure. If not, Altman said the Quarry will transition whenever the sewer is ready, but it would help with the economic hurdle to skip the septic and go straight to sewer.

“We want to be able to use that money to help canyon sewer, instead of going it our own,” Altman said.

Mangold added that new development, including the Quarry, would take on “more than their fair share” of early-stage costs—roughly one-third, upwards of $10 million—and that this is a chance to “stay out in front of new development,” leveraging private capital to fund the central solution.

“And if we don’t do it now, it may never happen,” Mangold said.

For all private properties and new developments across the corridor, Mangold and Altman hope owners will forgo individual septic projects, avoiding those sunk costs and instead saving that money for an investment into the centralized sewer.

For example, the Big Sky School District recently reconstructed its septic system as part of its facility upgrade and building addition.

“And we would rather use that money to fund a central solution,” Mangold said—of course, the solution was far away when voters approved the school bond in 2020.

Now, the district is weeks away from applying for a DEQ permit.

Centralized sewer will require collaboration and sacrifice, but for the health of the impaired Gallatin River, project leaders believe the long-term benefits will outweigh the short-term costs.