Income gap reflects home purchasing ability

By Joseph T. O’Connor Explore Big Sky Senior Editor

This is the third installment in a three-part series on housing and development in the Big Sky area. Read the previous articles here and here.

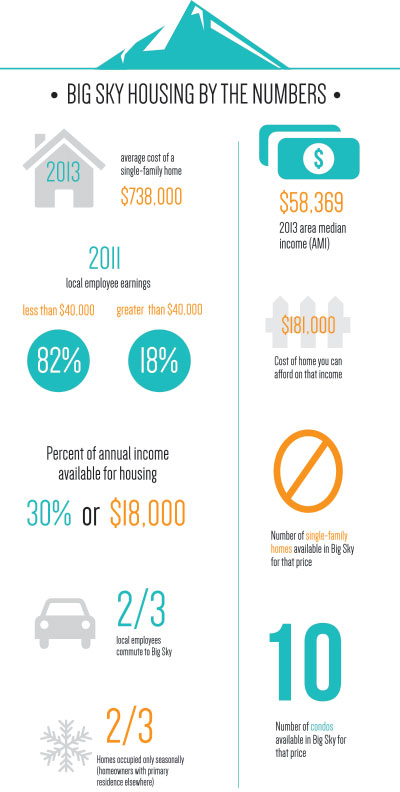

BIG SKY – The U.S. is today seeing its largest economic disparity in more than 80 years. It’s no more prevalent than here in Big Sky, where 82 percent of area employees earn less than $40,000 per year, according to a recent report. Meanwhile, the average cost of a single-family home here was $738,000 in 2013.

On Feb. 19, Economics and Planning Systems, a Colorado-based consulting firm, released preliminary findings for a Big Sky housing study it’s been working on since last November. The project was paid for with local resort tax dollars and conducted to answer questions about why there is a shortage of reasonably priced housing in the area.

Last June, the local Resort Tax Board allotted the Big Sky Chamber of Commerce $80,000 to hire a consultant to perform a housing development plan, and on Oct. 18 the chamber hired EPS.

A firm that has performed similar studies in Aspen, Telluride and Vail, Colo., as well as in Teton County, Wyo., EPS presented its preliminary findings at a Feb. 21 meeting to a panel of representatives from local, regional, state and federal organizations.

The purpose for the meeting was to examine funding opportunities for a housing development plan, according to Big Sky Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Kitty Clemens.

“We are way behind the 8-ball,” said Clemens, who has led meetings to discuss the area’s housing issues since February 2013. “Aspen does the best job, and they’ve been doing this since the ‘70s. Vail has been doing this for [more than] 20 years.”

Greater Big Sky’s area median income is $58,369, according to EPS’ report; by earning this salary, area households can afford to purchase a home valued at $181,000, the report said.

“If you spend more than 30 percent of your income on housing, you don’t have money for the other basic necessities of life including food, education and healthcare,” Clemens explained. “Almost every [mortgage] lender out there uses that 30 percent guideline in terms of qualifying people for a loan.”

Clemens will present EPS’ preliminary findings at a March 13 town hall meeting at the Warren Miller Performing Arts Center. Representatives from EPS will not be present at the meeting, but the firm plans to make a recommendation to the community once it has gathered and analyzed all of the housing development plan data in mid to late April.

———————

Housing in Big Sky is not a new problem.

Housing in Big Sky is not a new problem.

While the high-end market is seeing a boom in development, construction and sales, there is a notable shortage in lower- to mid-range homes, both for purchase and rent. Contractors are building homes ranging from $250 per square foot to $1,000 per square foot in the Yellowstone Club and in the greater Big Sky community.

As of press time on March 5, the cheapest single-family home in Big Sky was listed at $379,000.

Possible solutions have been discussed for nearly 20 years in this unincorporated Montana town of approximately 2,500. By bringing EPS to the table, residents and community leaders have taken action.

Daniel Guimond, principal at EPS, recognizes the answer won’t come easy. “It’s going to take fairly substantial resources to tackle the problem… and to get a sufficient number of units built,” he said.

Led by Clemens, a series of meetings took place in Big Sky beginning in February 2013, aimed at resolving the housing issues. Stakeholders and concerned community members discussed seasonal worker lodging, but Clemens says the shortage of housing for the area’s working professionals was the impetus for the meetings.

“Businesses [in Big Sky] have told me they need to hire talented people, but there are not enough places for talented people to live,” Clemens said.

She prefers the term “workforce housing” to “affordable housing,” to clarify that the plan would not include federally subsidized Section 8 housing complexes.

According to the report presented on Feb. 21, a number of options to fund a housing plan and land use regulations were discussed, including tax-increment financing (TIF), essentially an additional mill levy that could subsidize development; land set-aside options, which require a certain amount of land designated as affordable housing; and Low Income Housing Tax Credits, a federal program.

Some of the solutions used in other areas aren’t available to Big Sky, Guimond said.

“A lot of the approaches taken on by other resort communities are not possible at this time because [Big Sky is] not incorporated,” he said, pointing specifically to inclusionary housing ordinances, which require a percentage of an area’s housing to be affordable, and commercial linkage fees, which refer to impact fees assessed for new commercial development based on a need for workforce housing.

————————-

Vail first addressed the housing question in 1973, when it adopted the Vail Plan, an 18-page document that, in part, ensured the availability of more affordable housing. It was portion of a bigger housing plan to grow the area as a destination resort, according to George Ruther, Vail’s Director of Community Development.

“Hotels [and other infrastructure] cannot be sustainable for five months out of the year,” Ruther said. “We needed to have a year-round economy, including a year-round workforce, and those employees needed affordable places to call home.”

In 1990, 25 residents filed a petition with the Vail town clerk declaring a need for a housing authority – a governing body that traditionally provides lower rent or mortgage options. The petition cited a lack of livable housing, and rested responsibility squarely on the town’s shoulders.

“[These conditions] compel persons of low income to occupy unsafe and unsanitary … or overcrowded and congested dwelling accommodations,” a subsequent town resolution said, “causing an increase in the spread of disease and crime.”

Then-mayor Kent R. Rose adopted the resolution in January 1991, effectively extending Vail’s battle for its workforce.

Since then, Ruther says, the town has provided workers viable housing. “We now treat affordable housing like our roads and fire departments and water,” he said. “It’s part of a necessary infrastructure.”

Currently, two-thirds of the workforce in Big Sky commutes from Bozeman, Belgrade or West Yellowstone, according to the EPS report.

But as the community prepares to welcome new employees and potential residents, there are options. A new grocery store and health care facility are both set for completion in the next 18 months, adding upwards of 50 new jobs.

Perhaps these employees will find homes in Big Sky.