Doctoral candidate investigates human impact on watershed

By Amanda Eggert EBS Associate Editor

BIG SKY – During the summer of 2015, Montana State University doctoral student Meryl Storb set up sampling sites up and down the Gallatin watershed to develop an inventory of stream characteristics of the river and its tributaries. She noted physical characteristics, water chemistry and temperature, evidence of natural or human-caused disturbance, and the population and diversity of aquatic life at each of seven stream sites from Beehive Basin to the Community Park in the heart of Big Sky.

Now she’s using that data to ask a new set of questions and strengthen her understanding of how the Gallatin watershed is being impacted by humans, from both a climate change and development perspective.

To do so, she’s enlisted the expertise of a colleague at the Payn Watershed Hydrology Lab, Juliana D’Andrilli, an assistant research professor at MSU’s Center for Biofilm Engineering and Chemical and Biological Engineering.

D’Andrilli’s research focuses on the smallest building blocks of the food web. She looks at organic matter to understand its production, transformation and uptake as it cycles through terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

“Our focus is the algae because that’s what’s called the primary production,” Storb said. “It’s the base of the food web, but it has a trickle up effect for everything else.”

They’ve been so busy taking measurements that they’ve had little time to analyze data from their latest experiments, but Storb said one thing that’s immediately apparent is how low the Gallatin River ran this summer.

The flows Storb and D’Andrilli observed in early August were more typical of what is usually seen in late September or early October, Storb said. She thinks this is due to warmer springtime temperatures—much of the precipitation that would have normally fallen as snow this spring entered the watershed as rain instead. “It’s not stored in the watershed as long [as snow],” Storb explained, adding that an earlier peak runoff also contributes to a longer growing season for algae.

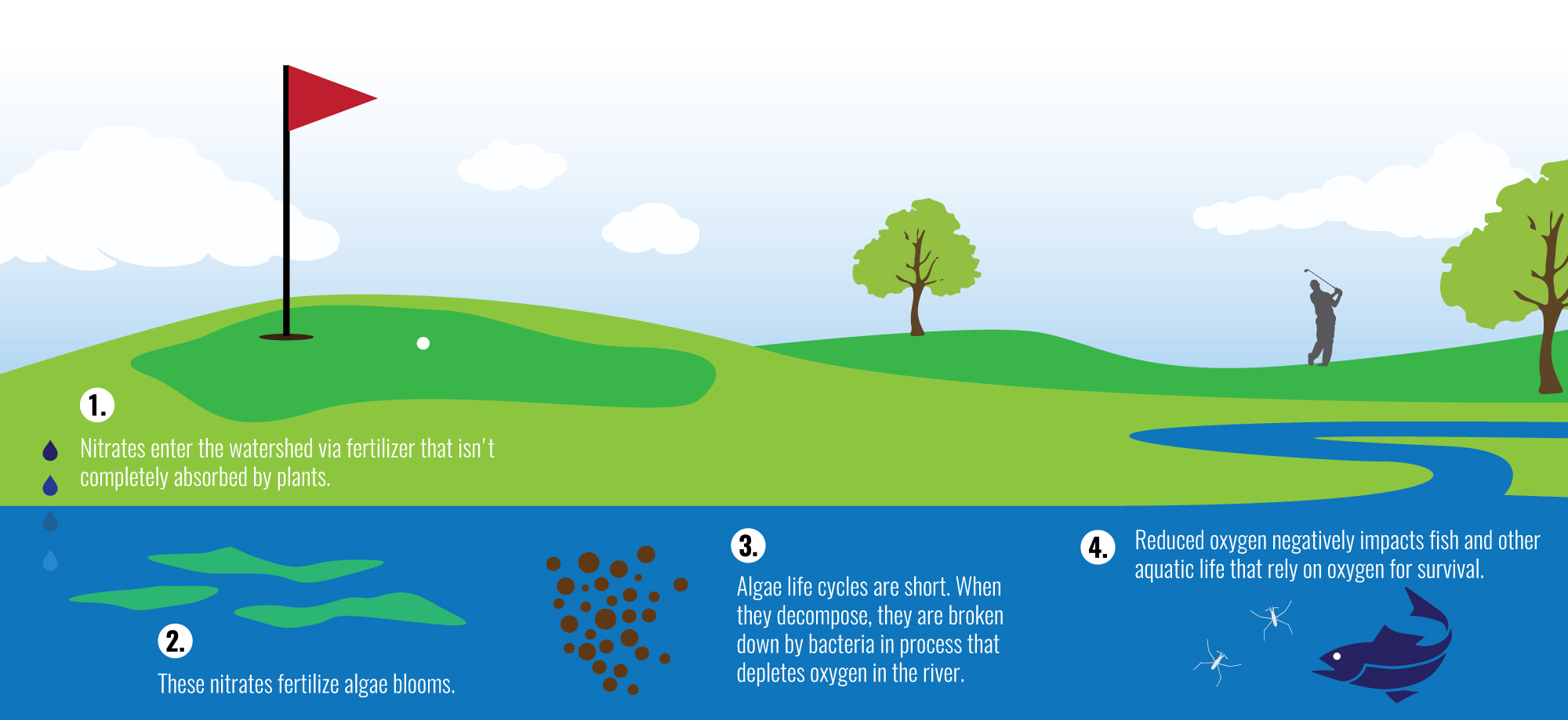

That’s problematic because when fertilizer-fed algal communities decompose, they reduce oxygen available to aquatic life. Bacteria consume the decaying algae in a process that removes oxygen from the stream. This process is called eutrophication.

Humans influence algal growth patterns by introducing nitrates into the watershed, which act as fertilizer for algal blooms. “Big Sky’s a nice example because there’s a pretty big nitrate loading problem,” Storb said. “We’re introducing something that hasn’t historically or naturally been there and changing the dynamics of the system.”

Storb said nitrates—like those leaching out of poorly functioning septic systems and present in the treated effluent sprayed on Big Sky Resort golf course to fertilize it—are a potential source of nutrient loading. She said it appears some unabsorbed nitrates are entering the watershed, leading to an increase in algal biomass downstream.

Traditional water quality sampling often includes a nitrate measurement, but that alone won’t tell the full story of nitrate’s impact on the watershed. Since it’s so readily absorbed by algae, nitrates might not show up in water chemistry samples.

To get around this blind spot in the data, Storb and D’Andrilli take biomass measurements to gauge the size of the algal community at their sampling sites.

They’re also studying the Gallatin’s stream metabolism, the process by which the carbon cycle plays out from day to night. Storb has taken to calling this process “river breathing” to help people conceptualize how it works.

Like other photosynthetic organisms, algae take in carbon dioxide and respire oxygen during the day. Oxygen, which is measured in the stream as dissolved oxygen, is important for aquatic life like fish and the bugs they feed on.

During the evening, fish and aquatic invertebrates continue to take in oxygen, but there’s less of it available since photosynthesis doesn’t occur at night. Healthy aquatic ecosystems contain enough oxygen to support fish and invertebrates throughout the day and night.

Understanding how this dynamic works requires marathon sampling—which Storb and D’Andrilli started in June and plan to continue through November, assuming their sites aren’t frozen over.

Once a month, the researchers conduct a 24-hour sampling where they take a host of measurements every hour on the hour. During these sessions, they often go 24-plus hours with little or no sleep, which might explain why this dynamic exchange between dissolved carbon and oxygen has rarely been studied in river ecosystems.

“It seems like such a simple thing: let’s see how they change from day to night,” said Storb, who is working toward a doctorate in Land Resources and Environmental Science at MSU. “But it hasn’t really been done.”