‘The richest hill on earth’ had a dark underbelly in the early 1900s. Descend into … Butte: Underground

By Heidi Utz

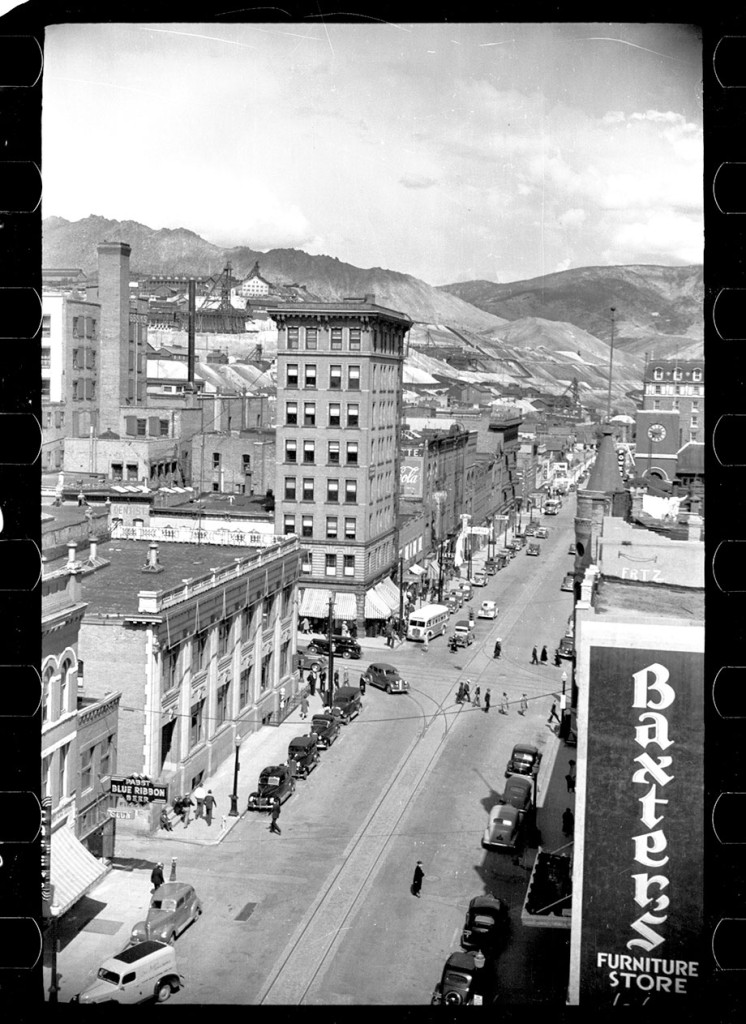

At the turn of the 20th century, the mile-high city of Butte, Montana, was a thriving metropolis. The town had quickly progressed from a smattering of mining camps to one of immense wealth from its gold, silver, and copper mines, and contained surprisingly modern amenities. The first skyscraper west of the Mississippi, Hirbour Tower, rose from the core of the city’s Uptown district, and electricity arrived in Butte in 1882, well before most large American cities had it.

Butte hosted a rambunctious mix of hard-working, hard-playing miners from around the globe, and high-rolling entrepreneurs who leveraged its rich copper mines for all they were worth. In Uptown, the two sometimes crossed paths beneath the sidewalks, in a web of back rooms and basements that formed the Butte underground.

Within a decade, the city’s population had swollen to more than 100,000 – three times its previous size – and about 130 establishments maintained spaces in the “sidewalk below the sidewalk.” Among their ranks were extensions of stores like Gamer’s Shoes, a barbershop, and a clutch of speakeasies that sprung up like wildfire in the wake of the 1919 Prohibition Act.

Kristen Inbody, writing in the Great Falls Tribune in 2014, paints a vivid picture of a town jam-packed

With a soaring demand for its minerals during WWI, bustling Butte employed enough miners and tradesmen to fuel “Venus Alley,” a renowned, round-the-clock red-light district that employed up to 1,000 ladies of the evening. The population spike also kept retail space at a premium, says local historian Dick Gibson, author of the well-researched historical account, Lost Butte, Montana. Basements could provide additional square footage that many business owners used to full advantage.

The underground was also the perfect spot for activities that thrived in the shadows. “There’s no doubt that opium was used in the back rooms of Chinatown,” Gibson says of the two-square-block area between Galena and Silver Streets. “In 2007 an archaeological dig found 18 broken opium pipes … The Chinese population knew how to use it recreationally, but some of the non-Chinese got addicted.”

And then there were the speakeasies. In a town where any hunger – gambling, prostitution, liquor, drugs – could be satisfied for a price, it’s not surprising that Prohibition did little to slow the tidal wave of indulgence that coursed through the “richest hill on Earth.” Gibson estimates 150 drinking establishments remained open in Butte during Prohibition, more than half of the 240 saloons the town had hosted prior to the rampages of Bible-thumping temperance movement radical Carrie Nation, famed for attacking bars with a hatchet.

Most prominently, the Rookwood speakeasy, tucked away in a basement cloakroom down a marble staircase in the Rookwood Hotel, served as an upscale gathering place in subterranean Butte. It attracted clients that may have included the mayor, police chief, and judges, to the two-way mirror at its clandestine entrance.

Operating today as a museum, the elaborately columned room was discovered by Mike Byrnes, formerly of Old Butte Historical Adventures, during a 2004 cleaning. Its terrazzo tile floors, stained-glass skylights, elaborately carved ceilings, and mahogany moldings inset with elephant hide had languished perhaps for more than 70 years in the exact condition they’d been left when the space was abandoned.

A green-felted poker table now sits on one end, while a carved hardwood bar with an American flag–draped backsplash shows where patrons once enjoyed locally bootlegged hooch. On the walls hang a wooden baseball betting board, some Art Nouveau prints, and several posters from the era advertising such libations as Olympia beer.

While the city was considered “wide open” for drinking, with cops being paid off to look the other way, the Rookwood did manage to find itself subject to at least one raid. On March 8, 1928, federal agents flew through its doors; destroyed its whiskey, beer, and wine stashes; and arrested notorious bootlegger Curly McFarland. It’s no wonder that most of Butte’s speakeasies sported trapdoor escape hatches.

Just down the alley, a less effervescent place to pass the time was the old city jail, aka the “Butte Bastille,” a dark, damp dungeon that occupied City Hall’s basement from 1890 to 1971. Considered a particularly brutal pen, here inmates endured lengthy interrogations, 100-degree temperatures, overcrowding, and discipline with weighted blackjacks and brass knuckles. Conditions were so bad that a 1971 federal investigation shut it down.

Now a museum with historical memorabilia, the jail once offered “three hots and a cot” to daredevil Robert (“Evel”) Knievel, who did time for reckless driving cheek-to-jowl with suspected murderer William (“Awful”) Knofel in 1956. Of their tandem incarceration, a prison guard once remarked, “What a place! We’ve got Awful Knofel and Evel Knievel!”

The city’s underbelly also saw its share of gambling, at places like the famed M&M Cigar Store at 9 South Main Street, which opened in 1890. In Prohibition-era Butte, a “cigar store” was a euphemism for an illegal bar, and thirsty patrons quickly sussed out their locations. Hosting miners and other carousers

In the 21st century, Butte has morphed into a calmer town of about 34,000 that feels more like a movie set, as its 4,000-plus historic structures in nine square miles form one of the country’s largest National Historic Landmark Districts. Old Butte Historical Adventures donates its profits to restoring some of these buildings – which means that more pieces of the underground could potentially be uncovered.

A number of local edifices have been repurposed as loft apartments, retail establishments, or mixed-use commercial/residential buildings. Both the Sears Building and the Leonard Hotel have been completely renovated, and the once-dilapidated, 100-foot Hirbour Tower has been transformed over the last five years into a condo complex with retail shops. Considered to sport the best-preserved sub-sidewalk storefront in town, the Hirbour housed an underground barbershop with a speakeasy for customers in the late ‘20s and early ‘30s.

In a town this rich in history, Butte’s underground gives us a window into southwest Montana’s rollicking past and a sense of what it must have been like to live in a place that transformed from mining camp to free-wheeling, free-spending boomtown at the speed of a stamp mill crushing ore.

This story was first published in the winter 2016 issue of Mountain Outlaw magazine.