By Julia Barton EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

BIG SKY – Peering down the Gallatin Canyon, toes dangling off the edge of the Green Bridge, the early summer weather feels great on the skin. The unusually hot temperatures over the past few weeks do not, however, treat the Gallatin River as kindly. As we look forward to having fun on the water in the coming months, there are rising concerns for the health of the ecosystem of the Canyon’s main artery.

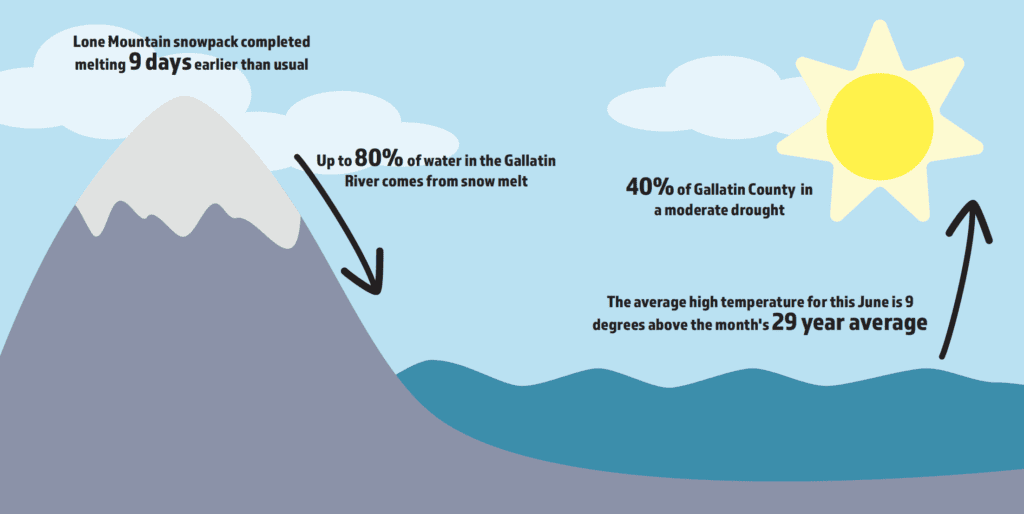

Up to 80 percent of the Gallatin’s water comes from snow melting off the high-alpine peaks in our area, according to the Gallatin River Task Force. The snowpack fueling the river is dependent both on how much snow is received during the winter and how much is retained by the landscape after snowfall ceases.

So far in June, the average maximum temperature in Bozeman is 81 degrees, 9 degrees above the month’s 29-year average recorded by the National Weather Service.

The abnormally high temperatures are pairing with drought conditions to exhaust the longevity of the snowpack. According to the National Integrated Drought Information System, 88 percent of Gallatin County is currently unusually dry; 40 percent of the county is considered to be in a moderate drought.

“Snow acts as a reservoir with a slow release into the river,” explained Lilly Deford, restoration director for the Gallatin Watershed Council. The river requires a certain amount of water to support a healthy ecosystem throughout the summer—as well as recreation activities such as whitewater rafting and fishing. Although the snow water equivalent, the amount of water in the snow, was between 90 and 100 percent of normal for the Gallatin Basin in March and April, the unusually high temperatures are depleting snow faster than normal.

Data from the Lone Mountain SNOTEL monitoring station indicated that the snowpack had completed melting nine days sooner than the median.

Earlier runoff due to unusual heat translates to below average streamflows, particularly for the latter end of the summer, explained Kristin Gardner, executive director for GRTF. “That also means we’ll likely see warmer water temperatures,” Gardner added, as shallow water heats up quicker.

Based on the weather in the Gallatin River Basin so far this spring and summer, Deford and Gardner agree there are potential concerns arising as a result of the depleted snowpack. The warm, shallow water provides an ecosystem in which harmful algae can thrive.

The stringy green Cladophora algae first appeared in a significant bloom on the main stem of the Gallatin in 2018 and appeared again last summer, said Gardner.

Apart from casting the river in a green “visceral ickiness,” as Deford put it, the algae also impacts the health of other organisms that call the Gallatin home. “When you have significant algae blooms, you also can see decreases in the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water,” Gardner said, which makes the water less suitable for trout and the aquatic insects that the trout feed on.

The warm water itself poses risk to the trout as well, said Patrick Byorth, Montana water project director for Trout Unlimited, an organization committed to river conservation and restoration nationally. Trout are cold-water fish that can compensate for a few weeks of warm summer water by moving up tributaries with cooler water.

“Now we’re looking at probably a month or a month and a half of hot water time,” said Byorth. “That’s stressful enough to eliminate a cold-water fishery if it happens too many years in a row.”

In other words, this year’s weather and snowmelt is unsustainable for the Gallatin’s trout population in the long run, threatening to drive them up to cooler water more permanently.

Luckily, there are measures the community can take to help mitigate the risks posed to the Gallatin’s ecology. Although the shallow, warm water provides a strong base for the algae blooms, the algae require nutrients to truly thrive, which come primarily from leakage out of Big Sky. The shallower the water, the more concentrated nutrients in the river will be, making it all the more important to be conscious of what we let flow into the Gallatin.

Emily O’Connor, conservation manager at GRTF, said individuals and businesses alike can help keep nutrients out of the river by properly maintaining their septic systems as well as using sustainable landscaping practices that require less irrigation and fertilizers.

One of the easiest ways the community can have an impact on keeping the river healthy, said O’Connor, is conserving water wherever possible. “I would encourage everyone in our day-to-day practices to make choices that help protect water quality and quantity,” she added, explaining that we occupy space in a very sensitive ecosystem.

Byorth expanded upon this, explaining that “restoring the sponge” (aka our area’s wetlands) is vital in increasing the amount of water the landscape can hold after snow runoff. The river can pull from groundwater storage in the later, hotter months. “If we can build resiliency by improving our wetlands so there’s that nice blanket of really rich, spongy soil, we can restore conductivity into our tributary streams,” Byorth said. “Then our fish can adjust to that changing pattern.”

From a community standpoint, it’s important that when you’re down enjoying time by the river to pay attention to signs that it may be in stress, such as spotting green algae or unusually low water, and make efforts to conserve water and leak fewer nutrients into the river. The GRTF, GWC and TU, along with other organizations in the area, are working hard on conservation efforts, but “there’s always more to do,” according to O’Connor, and the community—long-term residents and short-term visitors alike—play a major role in protecting the Gallatin so we can enjoy it for years to come.