By Paul Swenson EBS COLUMNIST

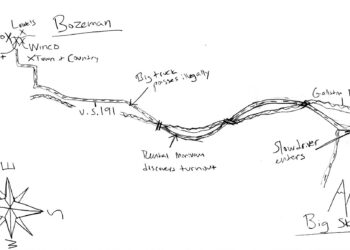

While I was skiing the other day I remembered a saying that a friend and I had back in the day when all we did was back-country skiing.

“Earn your potential!”

It was kind of a nerdy slam toward our front-country friends who skied the lift served terrain. So what did this mean?

Reminiscing back to physics class, a change in potential energy is the amount of work you have to put into, or take away from, an object to change its elevation in the gravitational field of the Earth. It is quite easy to calculate: PE = mass times elevation change, times acceleration due to gravity, PE=mgh. So as I rode up “Swifty” at Big Sky Resort the other day I did a mental calculation to find out how much potential energy the lift gave me. PE = 100 kilograms (220 pounds including my skis and clothing) * 800 meters (elevation gain in meters of the Swift Current chairlift) * 10 meters per second squared (the approximate acceleration due to gravity).

This resulted in a potential energy gain of 800,000 Joules. That’s twice as much as it takes to skin up to the ridge above Beehive Basin, not taking into account the friction and drag breaking trail. So we can pay for the energy by buying a ski pass, or earn the potential by climbing the hill ourselves.

Of course, the great thing about gaining potential is turning around and losing it. Where does it go? It gets transformed into kinetic energy—the energy of motion—and into thermal energy losses due to air and sliding friction which is the fun part of this energy cycle. Then back onto the lift, or trail, to repeat the process.

Sitting down on the chair I hear snarky comments from other skiers about the use of carbon neutral electricity as advertised on the back of the chair in front of us. Big Sky Resort’s website explains how they use REC (Renewable Energy Certificates) to purchase electricity from the grid that is generated from non-carbon emitting sources including solar, wind, nuclear, hydro and biomass. REC’s are common in industry. They support the renewable energy market and help reduce the customer’s carbon footprint, enable generators, users, and stakeholders to know where their electricity is coming from, and provide documentation that the electricity is generated from renewable sources.

So it got me thinking about my carbon footprint for a day of skiing. I thought for sure my daily contribution to atmospheric carbon-dioxide would be tiny compared to the resort. I did some research online to find carbon footprint estimates for my daily goods and activities.

Alarm, cup of coffee—coffee, grown elsewhere, uses lots of water and has to be harvested, transported, roasted, packaged, brewed, then poured into my cup. In total, that’s estimated to be half a pound of carbon-dioxide per cup. Fried egg, 1 pound carbon dioxide per egg; bacon, 1 pound per slice; driving to the resort and home, 20 pounds (1 pound per mile at 20 miles per gallon); pizza for lunch, 10 pounds per slice; hamburger for dinner, 24 pounds for a half-pound burger; shower, 1 pound for heating the water; salad, 1 pound for dinner. Holy cow, that is a grand total of about 80 pounds of carbon dioxide I contributed in one day, by these estimates.

Now let’s go back to the Swifty ride requiring 800,000 Joules of energy. Seems like this is gonna be a lot, but based on a physics idealized situation—without friction taken into account, just the vertical gain, and ignoring the other carbon-emitting factors tied to building and manually operating a chairlift—it comes out to .02 pounds of carbon dioxide per ride. Ten rides equal .2 lbs. Guess my riding the lifts didn’t even equate to the amount of carbon dioxide produced by a single slice of bacon. Goodness, not the result that I was expecting. Now I have some talking points on how to answer the comments from others around me.

But if we look at a resort as a whole and assume an average of 500 kilowatt motors on the lifts, we can estimate that an entire day of operations creates a total of 12,000 pounds of carbon dioxide equivalence. Then divide that by the number of skiers on the mountain—let’s just say 3,000 to be reasonable—and that becomes 4 pounds of carbon dioxide per person for skiing. That’s still 20 times less than my daily contribution from eating and driving.

Climate change seems to still be a debatable topic for some reason, but surely this winter has been kind of a wake up call for all of us that enjoy winter. January was the warmest on worldwide record by .7 degrees Celsius, and the average ocean temperature is .5 degrees Celsius higher. Around Montana there were record cold temperatures for a few days in January, but that did not offset the warm temps the rest of the month. January 2024 was the driest January on local record and had record warm temperatures.

For us old guys we can say, “When I was a kid we didn’t have snowmaking. Didn’t need it either.”

So this article is not to change your mind or your behaviors, just to give you some talking points next time the person on the chair next to you starts trash talking Big Sky Resort’s attempt to help maintain our way of life. We all contribute to the problem, and carbon output seems to depend less on whether we skin or sit—a difference of about 4 pounds of carbon dioxide—and more on the daily consumption habits many of us share.

Perhaps a bigger difference lies in how the potential is earned, cash or sweat.

Paul Swenson has been living in and around the Big Sky area since 1966. He is a retired science teacher, fishing guide, Yellowstone guide and naturalist. Also an artist and photographer, Swenson focuses on the intricacies found in nature.