O’Connor hopes the program’s “permanent benefits to the community” will entice donors

By Jack Reaney STAFF WRITER

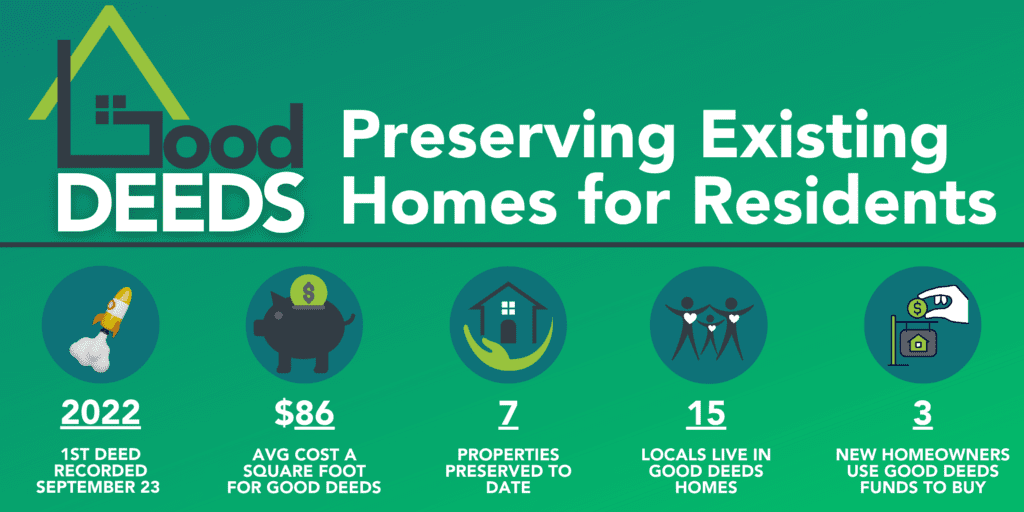

Dave O’Connor, executive director of the Big Sky Community Housing Trust, was unsure they’d find a single Big Sky homeowner interested in collaborating with the Good Deeds program in its first year. Instead, Good Deeds found seven.

Now halfway through the annual budget cycle, Big Sky’s new workforce housing machine has already exhausted its $855,000 budget.

Good Deeds is a program that allows BSCHT to participate in the real estate market, rather than manipulate or fight it—those tactics are also employed by BSCHT as they build workforce housing and charge rent below market value, and sell units with stringent deed restrictions that prevent significant value appreciation.

Good Deeds is designed to complement those housing efforts. A property owner can cash in on the actual market value of their home in exchange for placing a permanent deed restriction that ensures two conditions: short-term rentals are permanently prohibited, and qualified buyers must include at least one resident who works full-time in Big Sky for ten months of the year. If the early success of Good Deeds continues, the result will be a network of workforce housing woven organically into the Big Sky community.

“That’s really the two goals of Good Deeds,” O’Connor said. “To protect from losing more [housing] inventory to the short-term rental market, and to specifically earmark a significant amount of housing stock in the community for resident workforce.”

O’Connor said that by January 2022, the housing trust knew Good Deeds would be funded by June. However, they didn’t know if landowners would want to participate, and it was unclear whether the monetary and intangible incentives—the intention to positively impact the culture and community of Big Sky—offered by Good Deeds would trigger any transactions.

“And now approaching the end of the year, we know so many answers to those questions—now we’re ready,” O’Connor said. “We really feel that all the program needs now to keep moving forward is just replenishment. We’ve got the documents created and we feel very confident that there is plenty of demand from within the community. And [confident] that we would be continuing to make awards—a couple per month—as we were all summer, if we had funding.

“We’ve just got to refill the tank, and the motor’s ready to run.”

Now, BSCHT is raising money so they can keep the momentum of Good Deeds rolling until they receive a second round of funding in June—of this year’s $855,000, $750,000 came from Resort Tax, $100,000 came from the Yellowstone Club Community Foundation, and $5,000 came from the Knight Foundation.

O’Connor hopes that individuals and corporations will “see the permanent benefit to this community that this program [creates] and allow us to get back in the game as soon as possible.”

The housing trust is pursuing philanthropy and individual donations in time for end-of-year giving. Its online giving portal shows a current total of roughly $4,000 raised toward a year-end goal of $150,000.

For those who do give, O’Connor said “we’ll sing them from the rooftops.”

The housing trust will give public recognition to community members and organizations who help seize this opportunity to protect resident workforce housing.

“So many people have expressed a desire to help [with housing]. They want to try to do something to chip away at this problem. And this is a great way to do that,” O’Connor said.

“It’s not like a building where smaller donations can get diluted. This can really be something that we can collectively say as a community, [looking back] 20 years from now. And know that we have several hundred units in this community that are permanently protected for resident workforce… because it took all of us together. We need to tap into that generosity that’s out there among the community to keep this going.”

What makes a “Good Deed”

Big Sky is one of the first communities in Montana to implement this type of program, and O’Connor said a few other communities are interested.

Participants receive cash awards, worth between 10-16% of the property’s value. When a homeowner indicates interest, Good Deeds will conduct a property valuation and offer to pay a percentage in cash—drawing from its (currently exhausted) budget. If the homeowner disagrees on overall value, they can get an independent appraisal at their own expense. If that appraisal suggests a higher property value, Good Deeds will honor their original percentage if the new appraisal still fits certain guidelines.

The housing trust originally targeted properties worth less than $1 million. Given recent Big Sky housing market trends, O’Connor said that limit has been bumped up to $1.5 million on a couple occasions. The home must also be located inside the boundaries of the resort area district.

If an agreement is reached and the housing trust’s board approves, the homeowner will then receive that cash and a deed restriction will be permanently placed on their property. And unlike some deed restrictions which place an annual cap on property value growth, a “Good Deed” will not. If the homeowner wishes to sell their deed-restricted property in a favorable market, the only restriction is a narrower range of prospective buyers, as real estate investors and prospective Airbnb and short-term rental hosts are excluded.

“I can’t say with certainty this won’t affect your property values,” O’Connor said with regards to selling in a restricted market. “But what I can say with certainty is I have not yet found a lot of examples of communities using deed restrictions where it has had a negative impact substantially on property.”

He believes that if there’s a home listed for less than $1 million—like the properties that Good Deeds intends to deal with—it usually gets sold quickly, regardless of any restrictions.

Another key element of the Good Deeds program is that it allows homeowners to participate in the real estate market without having to leave Big Sky.

The program can apply to a homeowner who wants to sell their property, or one who plans to continue living there.

“Of the seven that we’ve recorded, it’s been a pretty even split… Transactions that were involved with a sale, and then some [homeowners] that are staying in place and not moving. But we’ve deed restricted their property—and they’re currently a member of the resident workforce so they satisfied their deed restriction right off the bat—so that when they sell, it will stay that way.”

In the meantime, a homeowner earns between 10-16% of their home’s value in cash.

“It allows property owners to cash in on the appreciation that the market has experienced without them having to move,” O’Connor said. “[That] benefits the community as a whole. Now we keep those people, and they might be board members and leaders and business owners.”

He also expressed excitement about the ability of Good Deeds to camouflage workforce housing among the community.

“It spreads throughout the community in a way that building projects can’t. It lets workforce housing become woven in the nature and the character of the community as a whole, instead of being just one neighborhood at the corner of it. Because that’s the nature of our community; we are a community that is largely composed of resident workforce.”

Goal for 2023: buy-down

Looking ahead of fundraising efforts to “refill the bucket” this year, O’Connor said 2023 could include a buy-down program, which he explained:

If the housing trust had, for example, $2 million available for homes on the open market, they could move quickly to purchase a property at face value and place it under deed-restriction. Then, the housing trust could turn around and sell it to a qualified buyer at a below-market price.

That discount in sale price, according to O’Connor, would be “the exact same” as the cash amount the housing trust would have offered to the seller (or homeowner) if they participated directly in Good Deeds.

In the same way that the housing trust uses its Good Deeds budget to pay that cash to participants, it could replenish that $2 million pool with money earned from the sale combined with a typical slice of their annual budget.

“At the end of the day, you have the same thing. You have a permanent deed-restricted property in the ground. But what this approach would let us do is, again, participate in the market instead of trying to fight against it.”