Adding social distancing to outdoor precautions

By Bella Butler EBS EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

A pair of skis; one to two mountain bikes, dependent on the size; a fully extended trekking pole—however you measure it—social distancing applies as much in the great outdoors as it does between four walls.

During Montana’s period of social distancing and under Gov. Bullock’s stay at home directive, people have flocked to trailheads for reprieve and much needed exercise. At the Big Sky Relief Fund Operational Partners Coordination meeting on March 27, CEO of the Big Sky Community Organization Ciara Wolfe reported an uptick in public use of BSCO trails. Rachel Schmidt, director of the Montana Office for Outdoor Recreation said colloquial reports of this trend have reached her from across the state.

“Getting outside is imperative, especially in times like these, and we’re lucky that we can,” said Dr. Maren Dunn, a physician with Bozeman Health Big Sky Medical Center. However, hikers, trail runners, skiers and the like are not absolved from the responsibility and priority of preventing the spread of the COVID-19 virus, according to Dr. Dunn. “Social distancing needs to happen outdoors as well as indoors,” she said.

She added that while the 6-foot buffer gets a lot of attention, there are two other aspects of social distancing that ought not be ignored: avoiding non-essential gatherings or crowds and limiting contact with people at higher risk.

“The outdoors is not a reason to think it’s okay to meet in larger groups,” she said.

Tania Lown-Hecht, communications director for the outdoor recreation and conservation organization Outdoor Alliance, echoed Dr. Dunn’s instruction, asking that those fleeing to the outdoors avoid meeting up with groups outside of individual not within their household.

Dr. Dunn offered the suggestion that even when abiding by the social distancing tenant of not meeting with an organized group, arriving at a busy trailhead may involuntarily place someone in a non-essential gathering, and it may be time to seek a less popular trail.

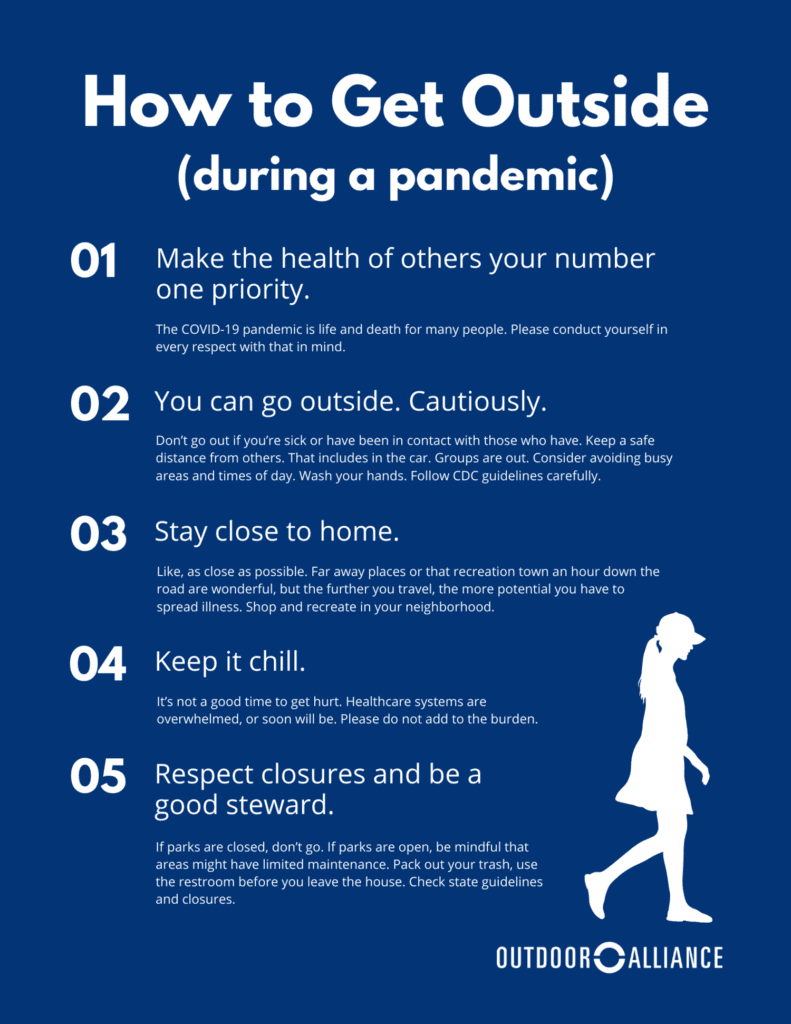

A graphic and blog post released by the Outdoor Alliance suggesting how to get outside during a pandemic emphasized the employment of social distancing as the utmost consideration for others when spending time outside, especially for those that may face more severe consequences if they were to contract the virus, complimenting the third component to social distancing mentioned by Dr. Dunn.

Along with the imposing health threats, increased traffic on trails can also strain the nature people are hoping to enjoy while getting outside. Schmidt, who said that the state is working hard to maintain public recreation areas to the best of its ability, stressed Leave No Trace principles and making an extra effort in the upkeep of these public spaces. “Just try to help maintain places that we love so much and make sure that we’re not adding undo traffic or harm or garbage, all of those things.”

Lown-Hecht added that visiting areas outside of peak hours can help distribute traffic, alleviating pressure on the environment as well as minimizing unwarranted disturbance, such as widening a trail to avoid spring mud.

A number of Outdoor Alliances’ organizational partners, such as the Access Fund, the American Alpine Club, the American Hiking Society and a host of others have released their own recommendations for specific recreation during the pandemic. A throng of themes have emerged from the collection of guides, chief among them being the avoidance of unnecessary risk.

“If you get hurt, if you need a rescue, you’re putting unnecessary pressure on an already overburdened medical system,” said Lown-Hecht. The Montana Office of Outdoor Recreation echoed her comments.

In addition to adopting lower-risk activities, a resounding national plea for people to limit recreation to areas only near to home aims to contain further viral spread, especially to vulnerable communities that double as recreational hot spots.

According to an article published around the dawn of COVID-19 concerns in the United States, Moab, UT, a popular spring destination for bikers, climbers and hikers, has only 17 hospital beds, many of which fill up with broken boned spring breakers. While Jackson, WY, another well-known recreation paradise, recently acquired 10 additional ventilators, the total is still only 22 for the town of nearly 10,000 people. Smaller destination and gateway towns have even less medical infrastructure and will be heavily taxed if continued visitation instigates a major spike in cases.

A blog post on the Access Fund website suggests taking this time to explore backyard public lands, parks and trails to grow a deeper appreciation for your immediate surroundings.

“Recreation and what we do outside in Montana is core to our identities as Montanans, so we are trying at every level to keep as much access as we can,” said Schmidt. “…[B]efore any of that, it’s important for us to watch out for the health and wellbeing in relation to the virus.”