By Bay Stephens EBS Editorial Assistant

BIG SKY – “Any more questions?” Mark Urich, 32, asked the assortment of first- through fifth-graders after an Oct. 30 presentation at Ophir Elementary.

Little raised hands gave way to exclamations of “I ski too!” Although it wasn’t a question, Urich couldn’t help but smile. He’s as stoked about skiing as the kids that surrounded him, although the way he skis is a little different.

Born with a Proximal Femoral Focal Deficiency (PFFD), Urich’s right leg was amputated above the knee when he was 2 so that prosthetics would fit better when he was older. Today, he is ranked seventh in the nation for adaptive alpine ski racing. His sights are fixed on representing the United States in the 2018 Paralympic Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

Sports and competition have been key to living a good life for Urich.

Growing up, his mom told him, “You’re as disabled as you want to be.” Since he was little, Urich has always charged, throwing himself into whatever sport he was doing. With only one prosthetic to work with for most of his life, Urich played baseball, hockey and football and got into rock climbing. At the University of Colorado Boulder, Urich rowed on the varsity crew team.

“There’s no better way to get people to not make fun of my leg than sports,” Urich said. “Once I figured out that I can use it for my advantage—I just might have to work a little bit harder—[it was] game on.”

Although Urich now races on the development team for the National Sports Center for the Disabled, carving out high-velocity turns all over the world, he’s been skiing for just six years. When asked about his introduction to the sport, he was straightforward: “A girl,” he said.

While managing a bar in Denver after college, a woman in a wheelchair came in and caught his eye. Urich went over to talk to her.

“What’s with the leg?” she asked.

“What’s with the chair?” he replied. After more banter, she told him he had to try out skiing. Her name was Alana Nichols. A three-time Paralympic gold medalist, Nichols earned her hardware in wheelchair basketball and alpine skiing.

A ski date ensued, comprised largely of Nichols ripping around in her sit-ski, giving Urich a hard time as he struggled to get down the mountain. That was just the beginning for him, though.

“If she can do this, I can definitely get my butt up here and do this,” he recalls thinking to himself.

After a few days of skiing, Urich talked to his coach about adaptive racing.

“He told me I was crazy. He’s like, ‘I just watched you take 45 minutes down a blue run, man,’” Urich laughed. “We still talk about that today because three months after that I went to [the U.S. Adaptive Alpine Championships] and I got ninth in downhill in Alyeska, Alaska.”

After that taste of the world of skiing, Urich set his mind to finding a way to do it full time.

After years of hard work—and going on a vegan diet, more recently—Urich is looking forward to another busy winter doing what he loves: training with his team in Winter Park, Colorado, and racing all over North America and Europe.

Skiing brought him to Big Sky, which cultivated a love for the sport beyond racing, namely tackling big mountain and backcountry lines.

In racing, though, Urich’s experienced camaraderie while training with other adaptive athletes that he says is unparalleled. He lives, eats and skis with his competitors—both American and international—so there is no hostility between them, he said, only shared joy in each other’s successes.

One of Urich’s goals is to garner more recognition for the Paralympics, which don’t even have television coverage. He wants “to get people to see how cool some of this stuff is,” he says, making the point that watching a blind skier tear down a downhill course is something from another world.

More exposure would also help athletes like himself get sponsored so that, like Olympic athletes, they can compete among

the best in the world without having to work multiple jobs.

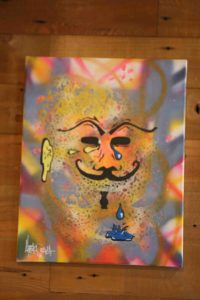

Although he has several sponsors—including Caliber Coffee, which sells a “Stoke Blend” in his honor—that allow him to get by with income from his graphic and web design business, Urich is always looking for more support. Gifted with his mom’s artistic talent, Urich also draws and paints. Several of his paintings adorning the walls at Beehive Basin Brewery are for sale.

Urich hopes speaking to kids like those at Ophir Elementary will help break down the current perception of disabilities.

“I want them to know I have just as much fun in life, if not more. That’s our joke,” he said of himself and his teammates, “‘Our life is your vacation.’ Do not pity us.”

“I think we need to move away from the ‘Oh my goodness, I feel so bad for that person,’ [approach] to ‘That person lives a different life, I wonder what happened,’” Urich said.

In the end, it’s all about perspective. It’s never been easy for Urich, but he has chosen a life of richness in the sports he devotes himself to, the art he creates and the relationships he fosters.

“I’ve gotten to see so many sunrises from the top of the world. Having one leg is not a bad life at all,” he said. “I’ve taken it and used it to be one of the coolest parts of my life.”

To learn more about Mark Urich or to support his racing, visit onelegski.com.