The recovery plan is the result of a multi-year lawsuit between environmental groups and the federal government.

By Amanda Eggert MONTANA FREE PRESS

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service this week released a final recovery plan for Canada lynx, a threatened, snow-adapted species partial to northern forests.

Recovery plans are sometimes called “roadmaps to recovery.” Federal wildlife managers use them to outline risks to a threatened or endangered species’ survival and identify objective criteria for measuring recovery efforts.

Threats to Canada lynx that USFWS identified in its recovery plan include a reduction of habitat in the western U.S. that’s capable of sustaining populations of resident lynx and a warming climate that’s reducing the wintertime conditions lynx rely on to hunt snowshoe hare, a rabbit that accounts for most of the lynx’s winter diet.

The plan arose from a legal settlement between the federal government and six environmental groups that had argued in a 2020 lawsuit that USFWS’ lack of action had left the species “in limbo.” Plaintiffs in that lawsuit, including Friends of the Wild Swan and WildEarth Guardians, also took issue with the agency’s 2017 determination that Canada lynx had recovered and therefore no longer required federal protection. That conclusion, the groups had argued, had “no scientific support.”

As part of the agreement, USFWS dropped its earlier plan to delist lynx in the Lower 48 and agreed to prepare a final recovery plan within three years. The agency’s announcement Wednesday follows the agency’s release of a draft plan in 2023.

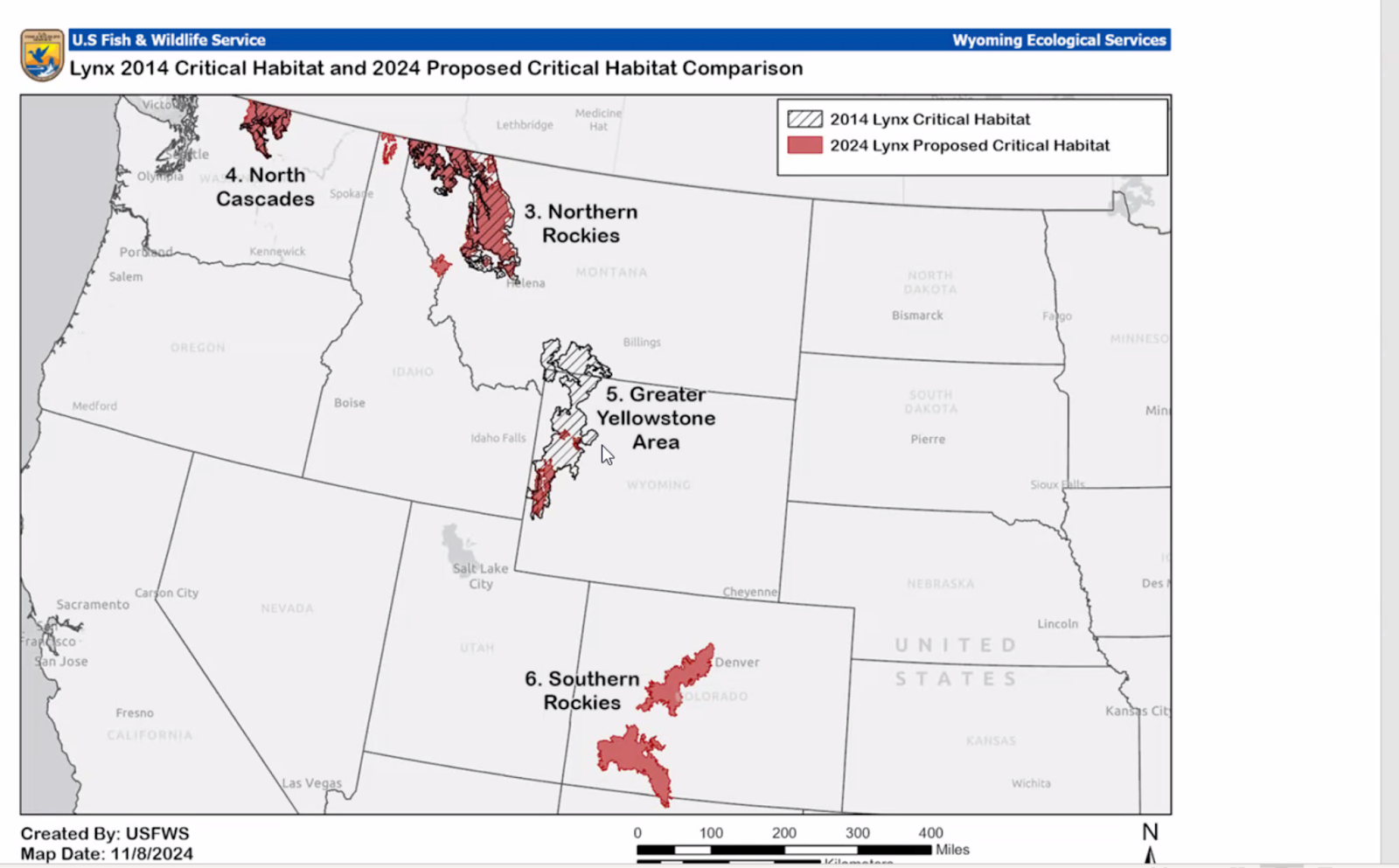

In addition to adopting a recovery plan, USFWS has proposed revisions to critical habitat — areas where land managers are expected to take particular care to avoid activities that could jeopardize the recovery of a threatened species. Such activities that affect lynx include trapping, including the trapping of other species, and logging.

WildEarth Guardians Conservation Director Lindsay Larris wrote in an email to Montana Free Press that she’s encouraged by the new plan and hopeful that the proposed critical habitat rule survives the upcoming administration change.

“Finally, after decades of litigation and political gamesmanship, we are encouraged to see the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service taking meaningful steps to protect the Canada lynx in the Western United States through a recovery plan and designation of additional critical habitat, including the Southern Rockies,” Larris wrote. “The Canada lynx is fighting to survive in the face of climate change and needs its habitat to be protected. This is what the Endangered Species Act requires, and we hope this proposed rule is finalized despite changes in the federal government.”

Jim Zelenak, a USFWS wildlife biologist who has been working on lynx management for a dozen years, said the proposed rule is based on research from the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station demonstrating that lynx are more prevalent in the mountains of southern Colorado than previously thought and less common in the northern reaches of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. As a result, USFWS has proposed removing critical habitat designation for southern Montana and much of northern Wyoming.

“There’s some boreal-like forest features throughout much of that country, but the new habitat modeling has kind of confirmed what we felt for a long time, which is that most of that Greater Yellowstone Area is not lynx habitat,” Zelenak told MTFP. “They occasionally sit down for a while [and] they may produce some young, but there’s not a resilient resident breeding population there.”

Matthew Bishop, a Western Environmental Law Center attorney who represented the environmental groups in their lawsuit against USFWS, wrote in an email to MTFP that he’s encouraged to see the proposed critical habitat designations for northern Idaho and in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. He said he intends to take a closer look at the agency’s decision to exclude much of the Greater Yellowstone.

The proposed rule will be open for public comment for 60 days. USFWS will review the comments it receives and is expected to issue a final rule in about a year.