The decennial process is nearing its close, but the debate over partisan advantage hasn’t quieted.

By Arren Kimbel-Sannit MONTANA FREE PRESS

After almost 13 hours of negotiation and debate Thursday about now-familiar subjects like competitiveness, proportionality and compactness, the Montana Districting and Apportionment Commission has adopted a new map of state Senate districts and set the parameters of the next decade of state legislative elections.

The newly defined 100 House districts and 50 Senate districts is technically still subject to change until the commission submits its plans to the Montana secretary of state in January. But with hard deadlines approaching, the window to alter at least the House map is effectively closed.

The commission approved a House map on a 3-2 vote at the beginning of the month, reapportioning the state’s voters to account for dramatic growth and population shifts over the last decade, especially in urban and suburban areas, a major sticking point between the commission’s two Republicans and two Democrats.

The five-person body is helmed by a nonpartisan chair appointed by the Montana Supreme Court.

Thursday’s objective was to consider amendments to the House plan based on public comment the commission received last weekend, as well as to pair the 100 House districts into 50 Senate districts, a task subject to just as much partisan scrutiny as every other step in this decennial process. Almost any decision the commission makes bakes in advantages or disadvantages for the major parties over the next decade of legislative elections.

The commission was also set to discuss how to assign holdover senators, lawmakers whose districts will change as a result of the DAC’s process in the middle of their four-year terms, to new seats, but ultimately kicked that debate to next week.

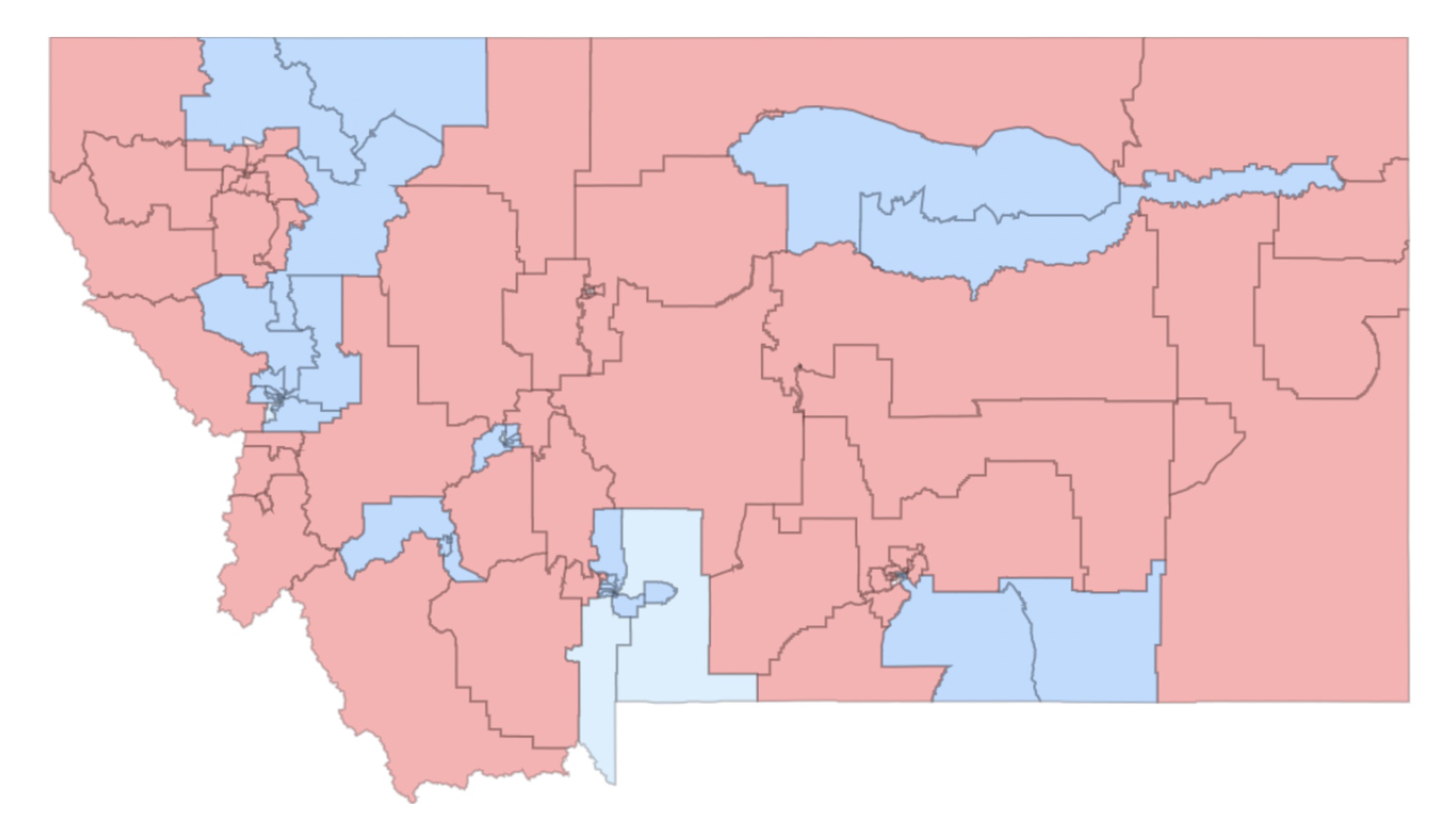

The new House map yields 35 safe seats for Democrats, five Democratic-leaning competitive districts and four Republican-leaning competitive districts. The remaining 56 seats are considered safe bets for Republicans.

On the Senate side, the commissioners agreed that Democrats would produce 21 Senate pairings and Republicans would produce the rest. Both sets of districts passed on 3-2 votes, with Chair Maylinn Smith breaking partisan-aligned ties. The approved pairings include 18 Democratic seats, a toss-up seat that includes Whitefish and Columbia Falls, two Republican-leaning competitive seats and 29 safe GOP districts.

Republicans argued, as they did with the House proposal, that Democrats drew lines and split political subdivisions to favor their party. Democratic commissioner Kendra Miller rejected that assessment.

“This is not a maximum outcome for Democrats,” she said. “It’s 18 lean-Democratic seats. With roughly 43% of the vote, we would be favored to win 36% of the Senate. There are three additional competitive seats on top of that. This is in no way maximizing anything for Democrats.”

Much of the commission’s debate has hinged around that 43%. Proportionality is not a commission criteria, though the body did adopt a goal of not unduly favoring any party. Nonetheless, Miller and fellow Democratic commissioner Denise Juneau have argued that the map should produce outcomes roughly in line with the parties’ average share of votes across the state as a whole. Over the last 10 major statewide races, that works out to about 43% for minority-party Democrats.

“57-43, that’s not a criteria,” Republican commissioner Dan Stusek said Thursday. “It never has been.”

The commission’s maps are bound by a series of mandatory criteria — compactness, contiguity, minimal population deviance and compliance with the federal Voting Rights Act, which protects minority representation — as well as commission goals, which include competitiveness and minimizing division of political subdivisions, among others.

Thursday’s work began with the introduction of a new House map from Republican commissioners Stusek and Jeff Essmann, who came out on the losing end of the vote earlier this month.

“What we’ve done since the hearing was to try to take their map and make some improvements that we thought might be possible after hearing from the public about where their priorities were.”

Much of that public comment focused on a few key areas. For one, the adopted plan created a Republican-leaning swing seat that includes parts of both Columbia Falls and Whitefish, replacing the more reliably conservative current Columbia Falls district. Rep. Braxton Mitchell, R-Columbia Falls, characterized the district as combining two diametrically opposed entities: a “hippy liberal ski town” in Whitefish and a more conservative, rural community in Columbia Falls.

That criticism was belied by the fact that the map Republicans advanced at the beginning of the month created the same district, though Essmann and Stusek maintained that was an effort to compromise with Democrats.

The Republican commissioners’ new proposal would also create a standalone Republican district in Belgrade, which under the previously adopted map would be split between two seats stretching out from Bozeman — one safe for Democrats and one swing seat. The Belgrade split was another source of consternation during public comment, with Republicans arguing for clear delineation between urban (read: Democratic) and rural (read: Republican) areas, though Belgrade, Miller noted Thursday, is Montana’s eighth-largest city and is on track to see significant growth over the next decade.

“We’ve kept Livingston whole, Havre, Colstrip — a whole host of areas that have been divided in the past now held whole,” Essmann said Thursday. “From an equity standpoint we believe Belgrade deserves no different.”

The new Republican-revised map was not ultimately put to a vote — that would have been a thorny prospect, given that the commission had already adopted and fielded public comment on the existing proposal. But it did form the basis of a number of amendments to the existing map, the most significant of which would affect the Belgrade and Whitefish-Columbia Falls districts.

Smith voted with Essmann and Stusek on an amendment redrawing the Belgrade lines to flip what had been a competitive seat to a safe Republican seat. But Smith joined Democrats in voting against separating Whitefish and Columbia Falls into separate districts. The commission also passed a series of amendments retooling district boundaries in parts of Cascade County and eastern Montana, though without any discernible partisan impact.

Whether those changes will appease Republicans or head off last-minute changes remains to be seen. In public comment over the weekend, Republican Party chair Don Kaltschmidt flirted with the prospect of litigation if the current map stands, though he told Montana Free Press he could not say exactly what the argument of such a lawsuit might be.

He also said some Republicans are interested in overhauling or reconfiguring the commission itself, which, due to the court-appointed status of the chair, has been swept up in broader conservative criticism of the judiciary. A number of bill drafts proposing changes to the commission, which is established in the state Constitution, are already in the hopper for the upcoming legislative session. Any such changes would ultimately require approval by the voters.

“We’re definitely thinking about it,” Kaltschmidt told MTFP. “The current configuration hasn’t worked out very well for the GOP.”

The map adopted by the 2010 Districting and Apportionment Commission yielded the first bicameral supermajority — 102 seats for Republicans — in modern Montana history this November.