Stakeholders applaud new protections while fighting for more

By Bella Butler

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to more accurately define the Gallatin Forest Partnership’s term “wildlife management areas.”

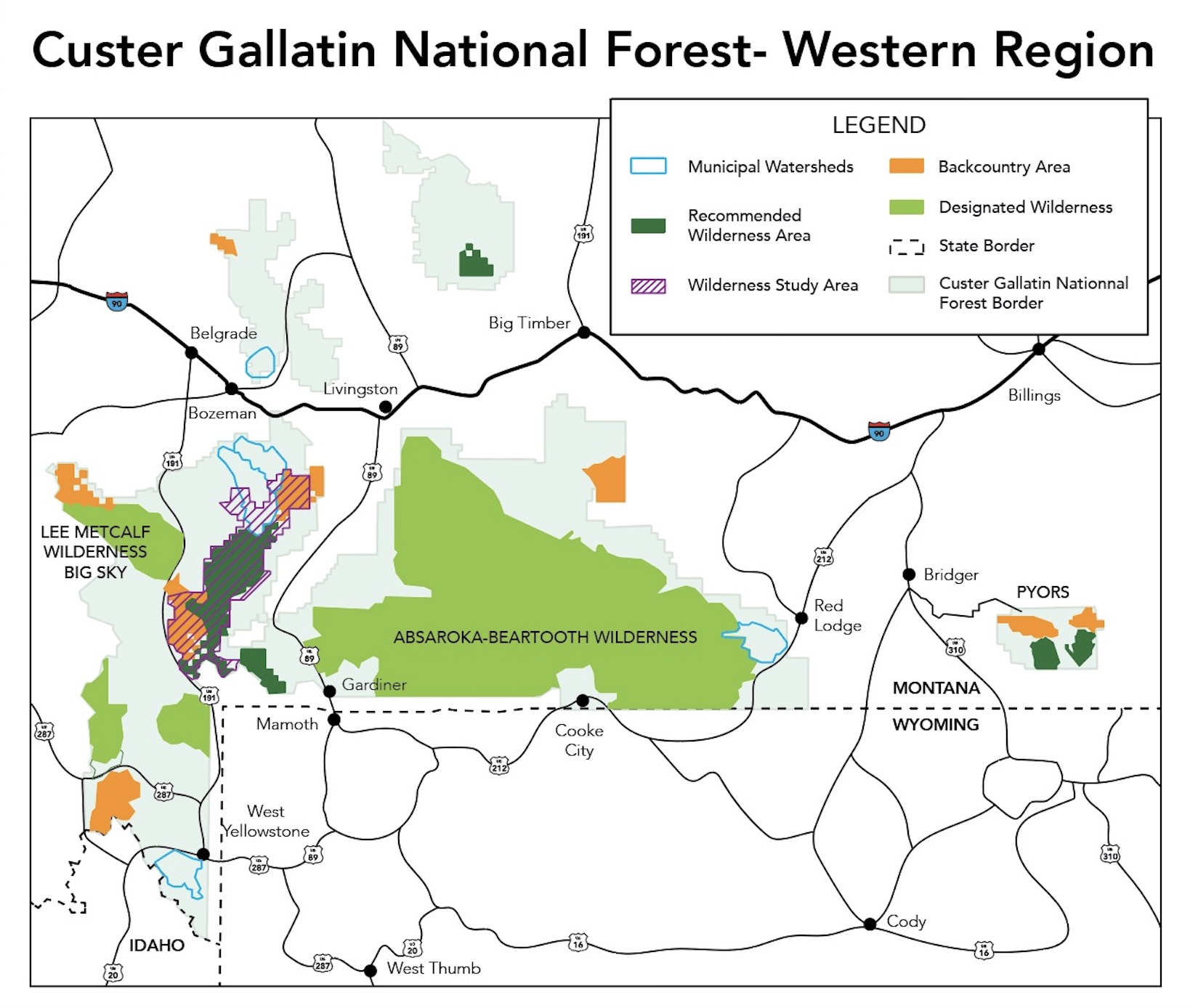

CUSTER GALLATIN NATIONAL FOREST – Roughly six years after Custer and Gallatin national forests merged to produce a joint 3.2-million-acre swath of protected forest, the U.S. Forest Service proposed its final plan for the management of the forest, renewing two former plans that were last updated in the 1980s.

In July, CGNF Forest Supervisor Mary Erickson published a final draft, offered as a preferred alternative, of the Custer Gallatin National Forest Land Management Plan after multiple years of public comment, evaluation and planning. The more-than-30-year-old individual plans were dated, Erickson wrote in her decision, and factors like increased wildland fires and an exploding population in the Big Sky and Bozeman areas warranted an updated approach.

“These changes in resource demands, availability of new scientific information, and promulgation of new policy … all speak to the need for an updated land management plan that is relevant and responsive to current issues and conditions,” Erickson wrote.

The 2012 Planning Rule created by the Forest Service guides the individual management plans of 154 national forests, 20 grasslands and one prairie. All national forests are reviewed and updated on rotating timelines based on this rule, and this renewal for the Custer Gallatin will be the first to join the two formerly independent forests under one unified plan.

Among the many components of the proposal is a list of recommended Wilderness areas. Wilderness designation provides the highest form of land protection that can be designated, shielding wildlands from activity such as resource extraction, road-building, off-road vehicular use and industrial development.

Wilderness is designated by Congress per the Wilderness Act of 1964, but the Forest Service, among other federal agencies, may recommend land for Wilderness designation. In the most recent forest plan, Erickson recommended more than 125,000 acres of land for Wilderness designation in the Custer Gallatin, including land in the Pryor Mountains; Absaroka Beartooth Mountains; the Gallatin Crest; Sawtooth Mountain; Taylor Hilgard in the southern Madison Range as well as the Bridgers, Bangtails and Crazy Mountains. The new plan also removed a recommendation for Wilderness in the Lionhead area south of Big Sky.

“There’s a lot of things in this plan that we are really happy to see and there are others that we’re disappointed about,” said Emily Cleveland, senior field director for the Montana Wilderness Association. MWA is a founding member of the Gallatin Forest Partnership, a coalition of 14 area stakeholders ranging from conservation groups to recreation alliances to outfitting businesses.

GFP launched in 2016, when the Forest Service’s revision and planning process began, in order to formulate a cohesive agreement informed by diverse perspectives about the management of Forest Service land. The partnership submitted its final agreement during the planning process in March 2018, which included 124,000 acres of recommended Wilderness in the Gallatin Range, Taylor Hilgard and Cowboy Heaven. Outside of the partnership, MWA was also an advocate for continuing the recommendation for the Lionhead.

“For this landscape (Gallatin and Madison ranges), I found the work of the Gallatin Forest Partnership to be the most compelling,” Erickson wrote in her decision. “This was due to the area-specific recommendations combined with local knowledge, and the outreach and coalition-building across diverse interests that accompanied their proposal.” Erickson also noted that the GFP agreement was endorsed by the Gallatin, Park and Madison county commissions.

Erickson included GFP’s proposal in an original draft of the plan that fielded public comment, but ultimately honored only parts of their recommendation in the preferred alternative of the final draft.

“What’s important about the Gallatin Forest Partnership agreement is that it’s a package of designations,” Cleveland said. “They’re all kind of intertwined and we as members all signed onto this agreement kind of looking at this as a collective group of solutions and so when pieces get chopped out it … threatens the integrity of our whole agreement.”

GFP also recommended the designation of 56,100 acres in the Gallatin and Madison ranges as “wildlife management areas,” a protection less stringent than Wilderness designation that still does not permit the use of motorized vehicles outside of pre-existing use. In the plan, however, Erickson calls these “backcountry areas,” which permit the continued use of pre-existing motorized and mechanized recreational activities.

One such designation was made in Cowboy Heaven, northwest of Big Sky in the Madison Range. “Our desire to protect the characteristics of this place is shared with the Gallatin Forest Partnership proposal, but I felt that this designation affords better flexibility to manage the rustic administrative cabin, primitive road, and grazing infrastructure and retains more options for future fuel and restoration work in the area,” Erickson wrote.

Erickson also dissented from the GFP agreement on the partnership’s recommendation for the Hyalite Watershed Protection and Recreation Area. This GFP proposal cited two main reasons for stringent protection and management of the area: Hyalite’s heavy recreational use and how the watershed provides the majority of Bozeman’s municipal water supply.

The forest plan classifies a portion of Hyalite, smaller than that recommended by GFP, as a “recreation emphasis area,” a designation that Erickson wrote establishes objectives for “increasing and enhancing recreational opportunities.” The plan includes nearly 225,000 acres of recreation emphasis areas.

Other key stakeholders recognized by the plan are indigenous nations that hold tremendous value in many parts of the Custer Gallatin. The Forest Service consulted with more than 19 tribes during the planning process and the plan recognizes “areas of tribal importance.”

Portions of the Crazy Mountains that are also sacred to the Crow Tribe are protected by the revised plan through recommended Wilderness and backcountry area designations. Shane Doyle, a Crow tribal member and the founder of Native Nexus, an American Indian education consulting firm, said consulting tribes was a key step for the plan.

“The Crow Tribe has had a long-standing spiritual connection to the Crazy Mountains for many hundreds of years, and we’re very pleased that the Forest Service has chosen to designate areas—ceremonial areas—which tend to be the higher peaks to the south and toward the eastern side, as Wilderness and backcountry,” Doyle told EBS on July 27.

“These are places where … for hundreds of years Crow people have gone to pray without food and water and believing that that’s a place of great spiritual power,” he added.

While Doyle expressed gratitude for the protections afforded to the Crazy Mountains in the plan, he also hopes to see more Wilderness designation beyond areas of Crow significance.

“Overall, for myself and for the tribe I think Wilderness is a high priority,” he said. “The Wilderness area is really the only way that we can maintain the integrity of quiet solitude that those places have enjoyed.”

The final draft of the Custer Gallatin National Forest Land Management Plan is currently in the stage of public comment, where those who have already provided public comment and engaged in the process have the opportunity to pose objections to anything in the draft for further discussion before the new plan is officially adopted. Cleveland said that MWA and GFP are still combing through the proposal and will present objections before the Sept. 8 deadline.

“The plan really is a balancing act of social, economic and ecological sustainability,” Mariah Leuschen-Lonergan, CGNF’s public affairs specialist wrote in a statement to EBS. “The Forest worked hard to build and maintain a robust public engagement process with over 100 public meetings and webinars, kiosks, youth engagement and much more and we had great engagement across the spectrum.”

In a video produced by CGNF, Erickson explores the draft plan and rationale for her decisions. She acknowledges that the Custer Gallatin is not only one of the most diverse landscapes, but also an area with some of the most diverse interests, making the planning process a true matter of compromise

“The process we’ve worked on and developed and engaged with people on, we’ve tried to pull that together and integrate our basic requirements under the law, really redeem our basic responsibilities for stewardship and then think about how you integrate all those values and perspectives into a framework for managing the Custer Gallatin National Forest for the next 10-15 years,” Erickson said.