Big Sky’s leadership gap is tied to its housing gap, which the RiverView development aims to bridge

By Jack Reaney STAFF WRITER

Community powers are collaborating to create a feasible path from entry-level employment to middle management, to property ownership and community leadership. According to the Big Sky Community Housing Trust, these are the tenets of building a life and supporting a family in Big Sky.

“The problem we’ve gotten into as a community is we’ve closed off too many entry and exit points to the path,” said Dave O’Connor, executive director of the BSCHT.

O’Connor has lived in Big Sky ever since graduating college three decades ago and he understands the challenges and merits of building a life in Big Sky.

Deed-restricted housing has been available since 2017, when Big Sky’s MeadowView condominiums were constructed to offer an opportunity for practical workforce housing ownership. Deed restrictions work to exclude investors by limiting home equity appreciation to 2% per year and mandating that buyers work and live full-time in Big Sky. Eligible buyers also must earn less than 150% of the area median income.

“It’s not going to be your lifetime home because of the [deed] restrictions attached to it,” O’Connor said. “But it’s designed to get you started.”

MeadowView provides an affordable working-class living option, and hosts 105 members of the community.

“If you made a list of everyone who lives there and their employers, it would read like a chamber of commerce membership list,” O’Connor said. “It did what it was supposed to do.”

Creating continuity in Big Sky’s workforce

Without deed-restricted housing options, Big Sky workers would need to earn 200% of the area median income—which roughly amounts to $140,000—in order to afford market value real estate in Big Sky, O’Connor said.

That’s why Big Sky’s community needs to fill “the missing middle,” he said.

“Our community is missing middle price, our employers are missing middle management, our community is missing its middle leadership,” O’Connor explained. “It’s a nationwide phenomenon, and it’s affecting Big Sky just as much.”

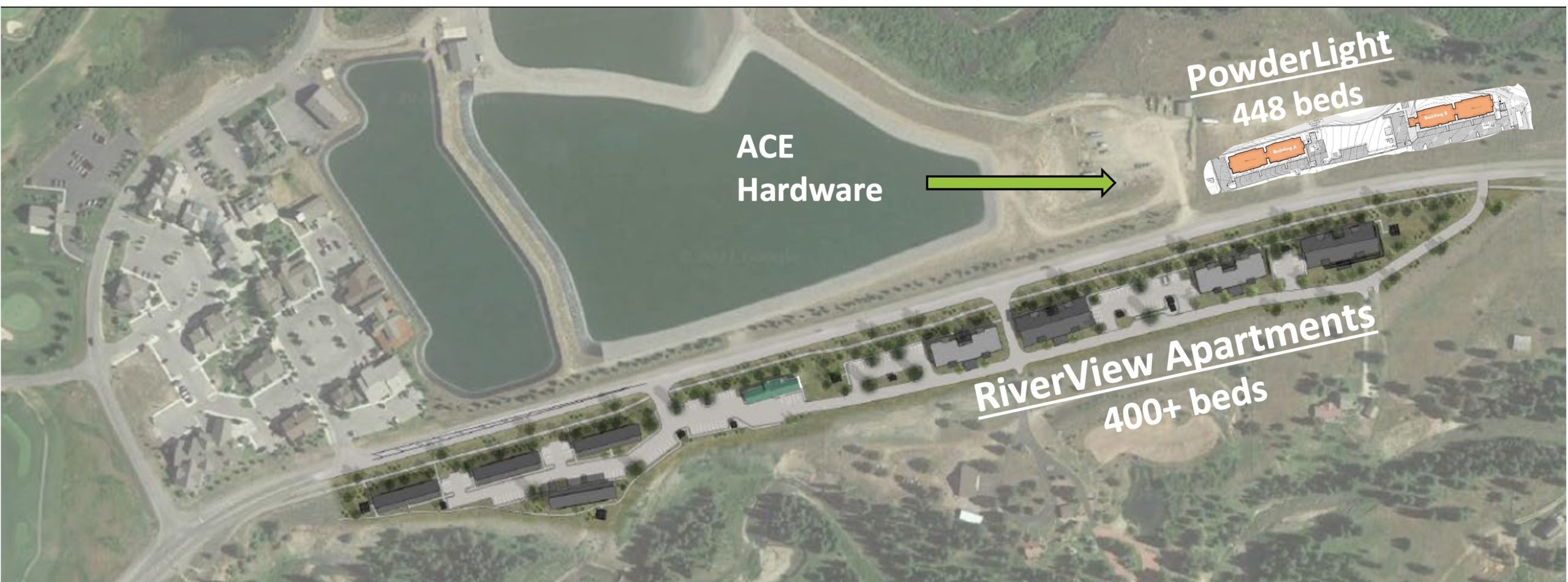

The housing trust is focused on providing an entry point and a path of upward mobility to keep locals living and working in Big Sky. Powder Light is currently being constructed to accommodate seasonal employment. The next phase in building that path is to target low-income renters from the full-time workforce. That’s why RiverView—the newest workforce housing endeavor––matters to Big Sky’s future.

A home for essential, low-income workers

In partnership with the Lone Mountain Land Company, BSCHT is supporting the construction of 100 apartment units on a long and thin slice of land beside Lone Mountain Trail (Montana Highway 64) across from the water reclamation facility ponds in the Meadow Village. Lone Mountain Land owns that strip of land and will operate 75 units, and BSCHT will operate the remaining 25 units on the westernmost portion.

Backed by a $6.49 million federal grant, the RiverView apartments will be structured through the federal government under the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program and administered by the Montana State Board of Housing. The only other local LIHTC program is the Big Sky Apartments, built in the 1990s on Moose Ridge Road in the Mountain Village.

To gain eligibility, renters will need to earn less than 60% AMI, which equates to less than $40,000 annually, and work full-time in the resort tax district boundary. Rent is set at 30% of total income.

O’Connor pointed out that Big Sky School District teachers, county sheriff’s deputies and certain medical professionals fit into that 60% AMI bracket.

“Not just low-income workers,” he said, “but essential workers.”

A nonprofit, the BSCHT does not have the capital or for-profit leverage to compete with private developers such as the Lone Mountain Land Company. However, in the resort tax amendment, which is funding Big Sky’s new Water Resource Recovery Facility, 500 single family equivalents of water were dedicated to the BSCHT.

“Now, we have water to bring,” said O’Connor. “What this arrangement did is it took the Housing Trust—in a position of deficiency by definition––and gave us a resource to bring back to the table and allow us to participate as partners.”

He added that Big Sky is unique in requiring partnership from so many parties, which shows how the future of accessible housing is a community-based solution.

A ticking clock

Construction has yet to begin on RiverView, as a valid easement continues to restrict the land. Held since the mid 1990s by the Big Sky Owners Association, the easement secured the construction of the paved bike path to the school district.

“In the end, this is a kind of real estate negotiation,” said O’Connor, whose BSCHT does not own the land and is not involved with the process of removing the easement. “Coming to an agreement on the value of an asset, and then transferring the value of that asset so that we can build. And that’s kind of what we’re in the middle of right now.”

If Lone Mountain Land and the Housing Trust are unable to break ground and lay foundations before the ground freezes, they will lag behind the completion milestones during 2023 set by the federal LIHTC program.

“We were awarded federal funding in the form of tax credits,” O’Connor said. “And if we don’t use them, we lose them.”

This article was corrected on Nov. 2 to accurately reflect professions whose workers earn less than 60% of area median income.