Understanding what digital slopes angle maps can (and can’t) tell you

Dave Zinn EBS Contributor

Avalanche terrain is defined as any snow-covered slope steeper than 30 degrees or areas immediately below, roughly equivalent to a steep black diamond or double black diamond run at a ski area. Correctly identifying avalanche terrain and understanding what hazards you are exposed to is fundamental to safe backcountry travel in the winter.

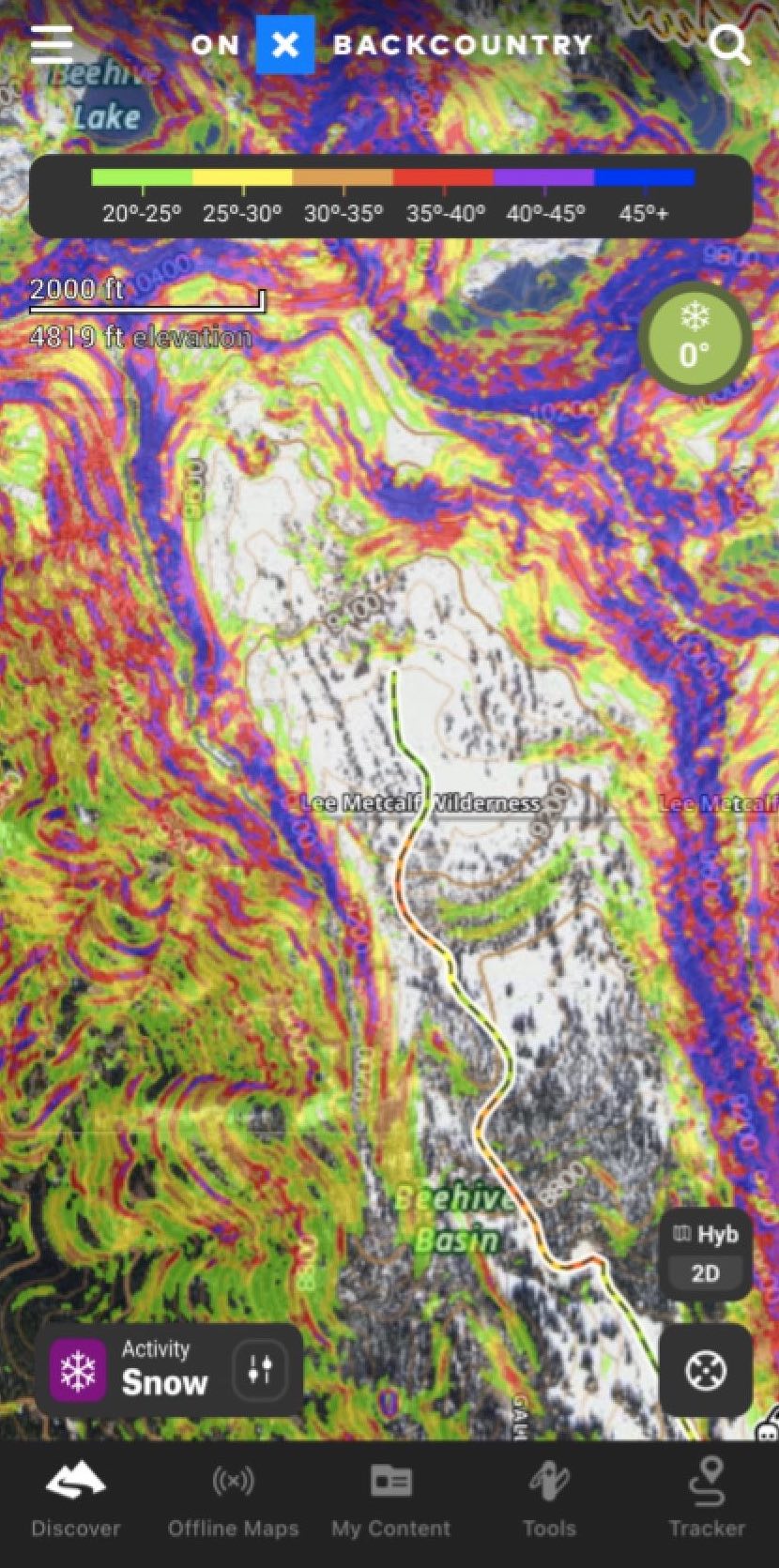

The proliferation of digital mapping programs such as onX Backcountry and Gaia GPS has made terrain identification easier with slope angle overlays that highlight steep terrain where avalanches are most likely (image 1). Like any tool, you must understand how to use these overlays correctly as well as their limitations.

Digital maps calculate slope angles based on the points of a Digital Elevation Model or DEM. In Southwest Montana, the available dataset is generally a 10-meter DEM, meaning that the points of the grid are approximately 33 feet apart, although there are more coarse and fine resolutions.

Like contour lines on paper maps, models can gloss over smaller terrain features that matter for avalanches, and there is a level of uncertainty even of consistent slopes. In 2006, William Haneberg calculated that with a 10-meter DEM, the minimum level of uncertainty is 1 to 2 degrees with errors often in the 3-to-4-degree range. Additionally, the models look at dry ground and do not account for changes in slope shape and angle due to snow cover and drifting patterns.

If your head is spinning and you are having traumatic flashbacks to geometry classes, simply understand that digital slope angle shading provides a good overview of slope steepness. However, you need to peel your eyes from your phone information, add an affordable slope meter to your kit and measure the slope angles on the ground (image 2).

Then, step back from the danger zone a few degrees to provide yourself a margin for error. For example, if I think a 31-degree slope is dangerous and could kill me, I am not going to ski or ride on a 29-degree slope because whether basing angles from a map or an inclinometer, I am just not that good!

Reporting from an avalanche that caught six people and killed one near Silverton, Colorado in 2019, the Colorado Avalanche Information Center outlined how the group utilized digital tools to plan and execute their route. Their trip plan was to weave their way through alpine terrain sticking to slopes less than 30 degrees, thus avoiding avalanche paths. The group tracked their route with GPS, so investigators know that they were “on or very close to their planned route” (image 3.a).

However, when the CAIC measured slopes angle at the site of the avalanche, they found the slope angle ranged from 32-34 degrees, within the normal margin of error based on the 10 meter DEM. With slope meter and a 3 meter DEM not available to the group, some of the finer details of slope angles emerge (image 3.b).

Should you throw away your phone and maps because they can’t be trusted? Of course not! Paper and digital maps are integral to trip planning and digital slope angle overlays take care of the math for you. With higher resolution models becoming available these tools will continue to get more precise.

Stick to the basics: avalanche terrain is any slope steeper than 30 degrees and the runout zones below. Use your tools and your eyes to determine if you are near or on avalanche-prone slopes. Don’t get lost because you are looking at your map.

Dave Zinn is an Avalanche Forecaster for the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center. He has been with GNFAC since 2019 and has eleven years of ski patrol experience at Bridger Bowl and the Yellowstone Club.