Local leaders and business owners learn from ‘sustainable tourism’ initiatives in Jackson Hole, Park City and Lake Wānaka

By Jack Reaney ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Local tourism and hospitality leaders are trying to balance Big Sky’s dependence on tourism with the needs of its full-time community. Visit Big Sky is setting its course toward a sustainable tourism economy, beginning a multi-year process to build a long-term master plan.

On Oct. 25, Visit Big Sky—the destination marketing branch of the Big Sky Chamber of Commerce—gathered community stakeholders and business leaders to discuss the future of tourism in Big Sky. Tourism officials from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Park City, Utah, and Lake Wānaka, New Zealand, shared lessons from their efforts to unify communities around a balanced and resident-focused approach to economies dependent on visitation.

The all-day workshop gathered almost 90 people for presentations, workshops and breakout discussions. EBS followed up with Brad Niva, CEO of the Big Sky Chamber of Commerce, who said Big Sky lacks a regular space for business-oriented discussions.

“The attendance was fantastic,” he told EBS. “It was definitely reflective of a need to talk more about tourism in our economy.”

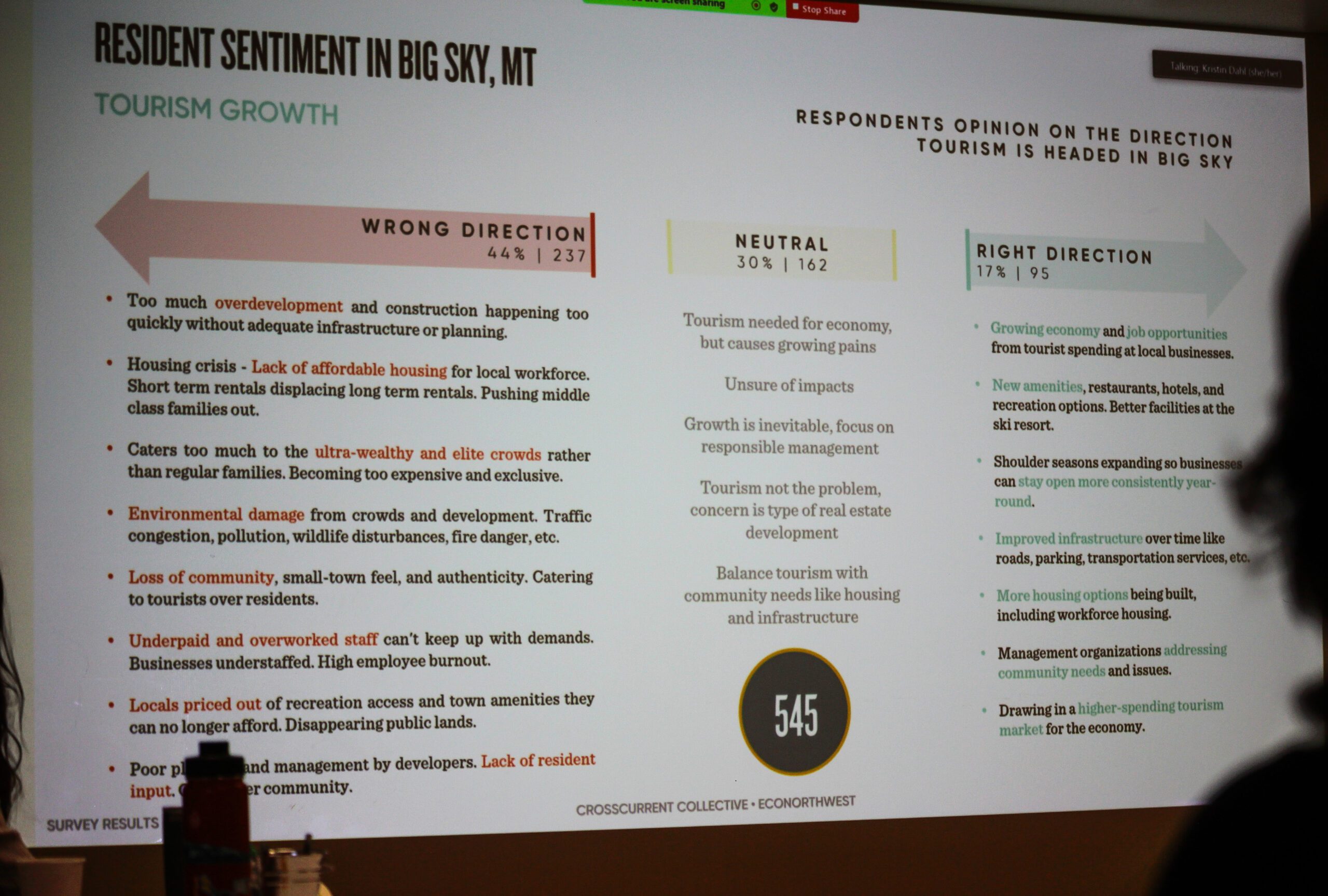

He emphasized that Big Sky needs to put residents first. From a recent survey, which collected responses from 545 locals, 44% responded negatively to the direction of Big Sky’s tourism; with 30% indicating a “neutral” feeling, only 17% feel optimism about the growing job market, amenities, housing, infrastructure and year-round community. Visit Big Sky also surveyed 1,600 visitors, and the final combined report is forthcoming.

Niva believes the October workshop pointed out a hunger to talk about tourism in this new way. He summarized the workshop’s central questions: Where is Big Sky now? Where do we want Big Sky to go? And without thoughtful tourism management, where is Big Sky going to go?

Destination visioning will explore the possible benefits of a year-round community with less extreme peaks and lows, Niva said.

“I think overall that there is a group of folks that love the seasonality,” Niva said. “However, the strain that it puts on our community, between housing and cashflow, is really challenging.”

These conversations will continue: Niva promised a series of themed public discussions to occur every two months. Next is a “Winter Tourism Marketing Outlook” on Dec. 5 at 9 a.m. at the Wilson Hotel.

“How many tourists are coming, what to expect for the season, and how healthy our economy is,” Niva previewed. He hopes to see not only business leaders, but community members as well.

Managing an upsurge

Tourism expert Kristin Dahl, founder and CEO of Oregon-based destination planning firm Crosscurrent Collective, opened the summit with discussion of broad trends in tourism since COVID:

“We just had this upsurge of people to outdoor recreation destinations, right? They all came in droves for the ‘Zoom boom,’ they wanted to work in these places, so we saw a lot of people moving. This is definitely happening globally, but for certain in the American West,” Dahl explained.

Showing a photo of a crowded Colorado ski resort, Dahl described “Extreme visitation, extreme congestion.”

Brad Niva took his job in Big Sky in the heat of that period, and within his first few days on the job in 2021, his organization lost half of its destination marketing budget.

“The community was really feeling the effects of over-tourism… There was certainly a negative connotation toward tourism,” Niva told EBS. Nationwide, tourism officials in popular destinations faced a challenge: the idea that cutting marketing budgets will decrease visitor numbers. Niva said to improve resident experiences, it’s far more effective to invest in destination management.

Whether tourism is booming or crawling, Dahl emphasized the importance of aligning local stakeholders under a shared vision of a healthy “tourism ecosystem.” Rather than focus marketing on the visitor, center destination marketing in the community.

One key to a sustainable tourism economy, she said, is for businesses to build trust and connections with each other. She sees that need—more local businesses and support—reflected in the Big Sky’s resident survey results.

“From a community or cultural standpoint, tourism ideally would be improving the lives of the people in a destination, not taking away,” Dahl said.

Tim Barke, CEO of Lake Wānaka Tourism, shared experiences from the ski and summer destination in New Zealand.

“The community told us: we want a place where our children can afford to live and have their own house,” Barke said. Lake Wānaka is a place where many visitors fall in love and some will decide to make it their home, he added. “One of the challenges we’ve found is that those people come here because they’re trying to get away from somewhere else, and then they try to turn this place into the place they’ve just tried to get away from.”

Barke emphasized the community’s desire to preserve its culture and livability. His team engaged local organizations, native tribes and conservation authorities to align objectives.

In one indigenous custom, visitors are not welcome until they understand the host community, and that community understands the visitor’s intention, Barke explained. Lake Wanaka Tourism replicated that in its destination marketing, encouraging visitors to not only visit, but stay longer and engage deeply.

Barke’s organization also created a community fund to help offset the strain of tourism and fund local projects—similar to Big Sky’s resort tax.

Jennifer Wesselhoff, president and CEO of Visit Park City, saw success with destination management in Park City, Utah.

When she started in Park City, residents blamed tourism for community problems—many wondered, “are we loving our community to death” with disruptive events, she recalled, begging the question: how much tourism is too much?

“The thing that we changed is, we’ve actually now realized what our job really should have been right from the start. Not just marketing and sales.”

TIM BARKE, LAKE WANAKA TOURISM

Her team worked to build a community-wide vision, improving local pride and connection, infrastructure planning, conservation and economic resiliency.

“Everything that we do now is in alignment… it has completely changed our priorities of our organization,” Wesselhoff said.

“Our number one customer is our community. It’s not our visitors,” she said.

Sharing the vision

In Wesselhoff’s prior role in Sedona, Arizona, the community responded differently to destination management efforts.

“Their plan, now, is about five years old and has really lost momentum. There’s a lot of great lessons around why,” she said. The main difference: in Park City, residents and businesses bought into a vision of the economy and sustainable tourism, understanding potential trade-offs. Visit Park City used “significant funds” for local messaging about that vision.

“We didn’t do that well in Sedona,” Wesselhoff said. “The result was that the community created their own stories about what we were doing and why we were doing it, that weren’t accurate.”

Crista Valentino, executive director of Jackson Hole’s Travel & Tourism Board, emphasized that a change in sentiment follows the feeling in the community; if locals disagree with destination management or don’t understand its purpose, the efforts will fail.

“We could put out campaigns to the local community and tell people all the time, ’tourism is great,’ but if they’re not feeling it [or] residents are feeling a negative effect, no amount of awareness or education campaigns are going to matter… I think that’s sort of a gut check for you all during this process… How do people feel about the work,” Valentino said.

Jackson Hole’s nine-month-old effort has a lot of momentum, she said. It takes quite a bit of work to prevent a plan from sitting on a shelf, requiring cross-community collaboration—building a shared vision breaks down silos because various organizations need to work together.

David Beurle co-facilitated the session. Founder and CEO of Minneapolis-based Future iQ, Beurle prompted the three destination leaders to share how they navigated tension during the shift to destination management.

Valentino said most tension came from the business side—a handful of people with a lot of money invested in development. Those folks called the effort “anti-tourism” and threatened to bring state officials into the mix to shut the process down.

“What it came down to was a fear: a fear of losing business, a fear of livelihoods and their investments going down, and what it took was building trust,” Valentino said. Difficult discussions, with support from allies, helped diffuse the fear.

“This was not anti-tourism, but actually, if we do it right, it’s kind of pro-tourism… [The] type of visitor that we want is actually going to stay longer, spend more money, care more… We’re actually going to improve your business, improve your workers’ quality of life,” she said.

“Sustainable or regenerative tourism is not anti-tourism. It’s actually just better tourism,” Valentino said, met by applause.

Barke faced similar challenges in Lake Wānaka. His team was surprised by the widespread support from most businesses.

“Not everybody; I’ve got one developer who [last weekend] said he’s committed to getting us shut down, because we’re not doing our job,” Barke said. “We’re exactly doing our job. The thing that we changed is, we’ve actually now realized what our job really should have been right from the start. Not just marketing and sales.”

Even in Park City, Wesselhoff found that this work can be tough when visitation drops.

“It would be a lot more challenging to have these conversations with our lodging partners because they want us to do marketing,” she said. “We’re using [lodging] taxes to fund our organization, fund our efforts, and they want those taxes to benefit them.”

Niva said tourism is challenging for Big Sky residents. Some feel that development is running away, and we’re putting tourism before community. He also pointed out some benefits of tourism.

“There’s always been a connotation that tourism doesn’t pay [industry employees] very well… If you look around Big Sky, you’ll find that it’s very well a living wage,” he said. Tourism is also essential to the hospital, school, amenities like Ace Hardware, “that have made our community much more of a community than just a [ski] resort and a hotel.”

Reflecting on last week’s community summit, Niva pointed out the comfort in sharing challenges with peer communities as far as New Zealand.

“We’re not alone,” Niva said.